This post is also available in: 简体中文 繁體中文

As a first-time mom, Lisa Xing faces tough questions in the face of increased racism during COVID-19

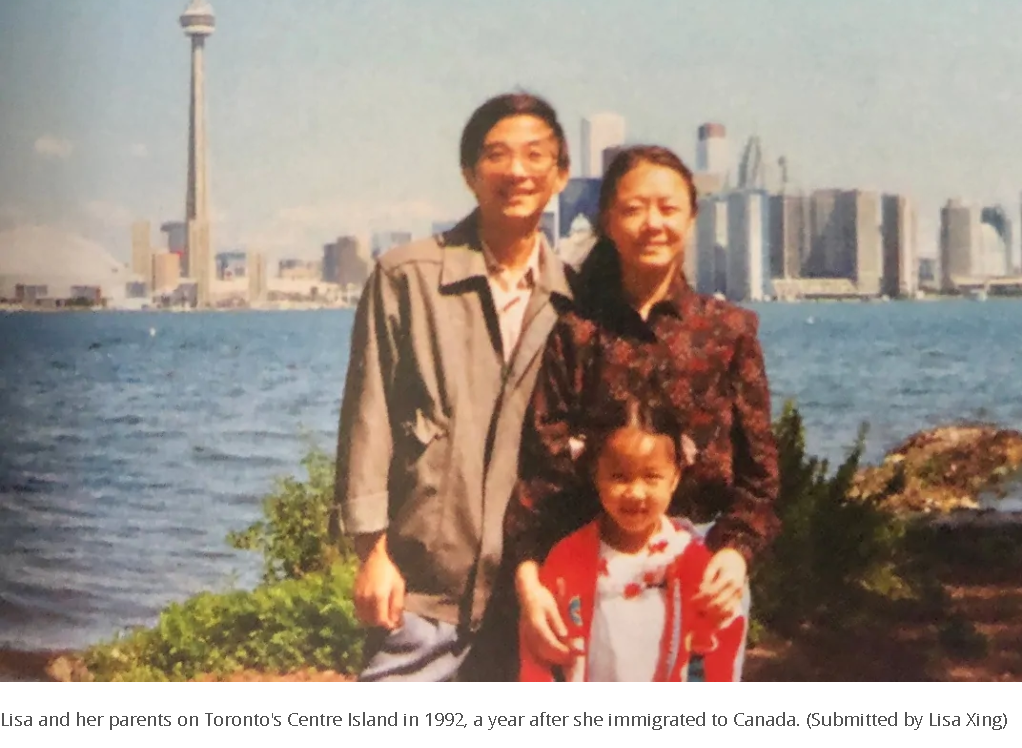

My parents immigrated to Canada from China in their thirties. I came when I was five. So I thought they would be honoured when I bestowed upon them the responsibility of giving their granddaughter a name. A Chinese name.

To my surprise (and dismay), I realized just how much they were against this child having a Chinese name. They said the first name should be easy to pronounce.

Finally, after my daughter was born on September 29, 2020, my partner Nathan and I settled on Minmin, pronounced “Ming Ming”. The first Min means “fall”, the second Min, “easygoing” and “gentle”. It was my mom’s suggestion, after she gave in to my pleas.

Not only do I think it’s user friendly, it’s beautiful written in Chinese as 旻旼. Both words using the same two radicals (parts that form a character), just rearranged differently.

The choice of my child’s name is just one way I am trying to instill a sense of pride in her Chinese heritage. I want her to embrace it, even though anti-Chinese racism has been on the rise since COVID-19.

My partner, Nathan, is white. He grew up on a tobacco farm in southwestern Ontario. Our baby is biracial.

Throughout the pregnancy, we often talked about how she would look, how I’ll manage to get her to speak Mandarin (as I am just a basic speaker myself), and the responsibility of choosing a name that would inevitably play a role in shaping her identity.

‘The China virus’

But although we went ahead and named her Minmin, the current social and political climate has wedged some fear into my mind.

It’s not treatment from kids on the playground that worries me. It’s the recent resurgence of racism that is different to the kind of intolerance I experienced as a child.

Trump calls COVID-19 the “China virus.” And since the coronavirus outbreak, there has been widespread racism against Chinese people, since the virus originated in Wuhan, China.

I hate to say it, but in this context, something as superficial as looking more “white” or having an English name could spare my daughter a lot of pain.

While I know she could get by easier by blending in, this hate also stirred up a defiance in me that made me want to instill that pride in being Chinese even more, so she can have a bulletproof attitude, as Nathan says, and so that none of it will bother her the way it bothered me.

What’s in a name

I wasn’t always called “Lisa.” My Chinese name is Yaxi (pronounced Ya-shee). That’s what I went by as a child growing up in Hamilton, Ont.

Everyone butchered it, intentionally or otherwise. Some called me “Taxi” or “Yucky”. So the summer before high school, my best friend – who also had a difficult-for-North-Americans-to-pronounce name, Yiqing – and I decided to change our names.

After fighting with my parents to let me change mine to “Melanie,” a cringe-worthy homage to Mel B of the Spice Girls, I finally relented and we went with “Lisa,” the English name my dad had chosen for me when I first came to Canada. Yiqing chose “Myra.”

The name change took some getting used to, though ultimately, it made life easier.

But some time after university, I started realizing just how unique my Chinese name was: Ya, the last part of my mom’s name, and Xi, which means “dawn.”

After my own experiences, and the ensuing struggle with my parents over my daughter’s name, I hope Minmin will embrace it.

I want her to be defiant and proud and confident.

And I hope she won’t take as long as I did to get there.

About the Producer

Lisa Xing has been a reporter and host for more than a decade. She has worked across the country from Edmonton to Halifax, and internationally from London, U.K. to Seoul, Korea. She loves sharing the personal stories of people who we may never otherwise meet, especially through the use of sound. She’s also a creative writer and photographer, with work published in The Wall Street Journal and THIS magazine

Article Source: CBC website ; Author: Lisa Xing