This post is also available in: 简体中文 繁體中文

Pfizer and BioNTech announced Monday that their vaccine candidate against COVID-19 has shown promising preliminary results in Phase 3 clinical trials. The vaccine is one of several that have been preordered by the Canadian government. So how close are we to getting the vaccine? What needs to happen first? And what kind of vaccine is this anyway? Here are some answers.

What did Pfizer announce about its vaccine results?

Pfizer said an interim analysis of data from its Phase 3 clinical trial, which is still ongoing, suggests the vaccine may be 90 per cent effective at preventing COVID-19 caused by the coronavirus.

The analysis was conducted by an independent data monitoring board. It looked at 94 infections recorded so far during the trial to see which occurred among those who received the real shot versus those who received a dummy shot or placebo. Each person gets two injections.

It did not say how many infections occurred in each group, but a 90 per cent effectiveness would imply that no more than eight of the infections were in the group that received the vaccine, Reuters reported.

What don’t we know based on these results? Why might the final results be different?

The results are preliminary, and the initial protection rate might change by the time the study ends, Pfizer cautioned.

The analysis so far looked for cases of COVID-19 seven days after the second dose. Pfizer has now said it will also look for cases 14 days after the second dose.

If the shot wears off quickly, the infection rate could go up among those who received it.

The company has not said how many of the infections so far occurred in older people, who are at highest risk from the disease. (Vaccines are often less effective in older populations, which is why there are higher-dose flu and shingles vaccines for seniors.)

Participants were tested only if they developed symptoms. That means it’s possible that some vaccinated participants could still have become asymptomatic carriers and were still able to unknowingly spread the virus.

Many people with COVID-19 have very mild symptoms, and it’s not yet clear whether the vaccine prevents severe disease or prevents transmission of the virus from an infected individual to someone who isn’t.

How well does the vaccine need to work to be approved?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has said a vaccine must be at least 50 per cent effective to be approved, ideally for preventing the disease but possibly for only preventing severe disease.

The World Health Organization recommends that, at minimum, it wants a clear demonstration that the vaccine is effective at least 50 per cent of the time in preventing the disease, preventing severe disease or preventing shedding or transmission. However, it says it prefers vaccines to have at least 70 per cent efficacy across the whole population, with consistent results in the elderly.

WHO also said the vaccine must confer protection for at least six months and ideally at least one year.

What kind of trial was this? How far along was it?

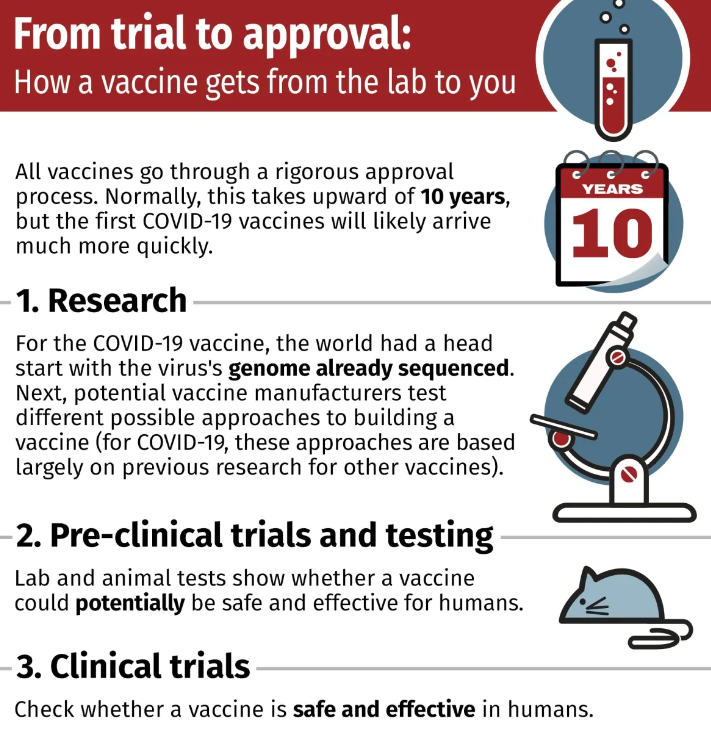

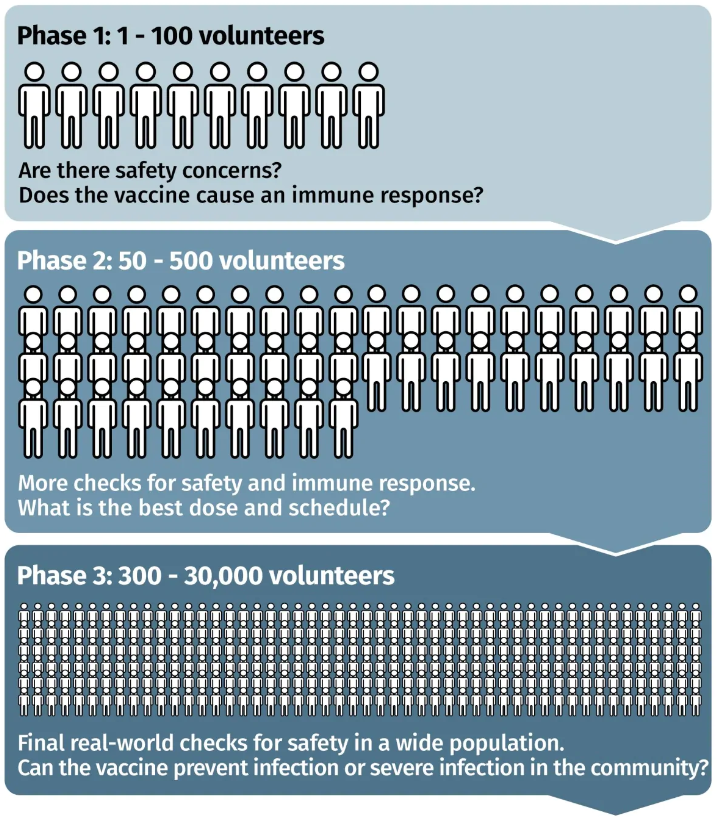

This was a Phase 3 clinical trial that started on July 27. It’s the final human trial step before regulatory approval. While Phase 1 and Phase 2 studies are focused mainly on safety, dosing and lab indicators of an immune response, Phase 3 trials answer a key question: are those who get the vaccine protected from the disease compared to those who get a placebo? It could also reveal rarer side effects that aren’t observed in smaller Phase 1 and 2 trials.

So far, the study has enrolled more than 43,000 people in the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Germany, South Africa and Turkey. Each person gets two shots, 28 days apart. Some get the real vaccine candidate, while the others get a placebo. So far, close to 39,000 participants have received both shots, Pfizer said in a release.

The Phase 3 trial will end when:

- 164 infections are recorded.

- At least half the participants have been tracked for side effects for at least two months.

That means the trial is waiting for 70 more infections among participants. Pfizer said it will reach its tracking milestone later this month.

How big a deal is this? How optimistic should we be?

Infectious disease experts say the results are promising.

Dr. Bruce Aylward, WHO’s senior adviser, said that Pfizer’s vaccine could “fundamentally change the direction of this crisis” by March, when the UN agency hopes to start vaccinating high-risk groups.

Vaccines won’t be available immediately for the general public in Canada.

Dr. Caroline Quach, a paediatric infectious disease physician and medical microbiologist at Sainte-Justine Hospital in Montreal, cautioned we’re not “out of the woods” yet, and everyone still needs to practise safety measures, such as handwashing, staying home when sick, physical distancing and wearing non-medical masks.

That’s because independent experts haven’t yet seen the full data to determine if the clinical trial participants who received the vaccine and placebo were similar enough to draw conclusions.

Experts also caution that the roll out of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to the general public will be slow, and logistical hurdles remain, such as the extremely cold temperature requirements for its genetic component.

What type of vaccine is this? What other front-runners are similar?

Pfizer’s vaccine is an mRNA vaccine officially called BNT162b2.

It consists of genetic instructions on how to make the modified spike protein from SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. The genes are encoded in mRNA and packaged in lipid nanoparticles. Once the vaccine is injected into the body, human cells use the instructions to make copies of the spike protein for the immune system to learn to recognize.

The technology includes Vancouver-based Acuitas Therapeutics’s lipid nanoparticles to deliver the mRNA after it’s injected into our cells.

Another vaccine in Phase 3 trials that uses mRNA technology is Moderna’s (which has also been preordered by the Canadian government). Two others, CureVac’s and Arcturus Therapeutics/Duke-NUS’s candidates, are in Phase 2.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of this type of vaccine?

This type of vaccine does not contain any virus or viral proteins, which means it can’t cause a real infection and is considered safer.

It is also relatively quick to manufacture.

Alan Bernstein, a trained virologist and president and CEO of non-profit CIFAR, a Canadian-based global research organization that brings together top researchers to address important questions, called the Pfizer announcement “great results for humanity.”

“There’s never been a vaccine made from RNA, so this is opening up a whole new world of making vaccines if this result holds up,” said Bernstein, who previously led a major HIV vaccine effort.

However, the mRNA vaccine is a novel technology, and no vaccines of this type have been approved for widespread human use.

One disadvantage of mRNA is that it’s not very stable. That means it needs to be stored at very cold temperatures. BioNTech’s CEO says the vaccine needs to be kept at -70 C for longer-term storage, although the company says it can survive five days in a refrigerator.

That may make it logistically difficult to distribute, especially in less developed countries.

WHO recommends that vaccines have a shelf life of at least two weeks in the fridge and at least six to 12 months at temperatures as low as -70 C. However, in the long-term, it says vaccines should be able to be stored at -20 C.

How much has Canada ordered?

Canada announced on Aug. 5 that it had preordered the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. It later specified that it had reserved 20 million doses, with the option to purchase more. Because two doses are required, Canada would initially have enough to vaccinate 10 million people if it is approved. The companies said the vaccine would be delivered “over the course of 2021.”

How much can Pfizer and BioNTech manufacture?

The companies say they can produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021.

Besides Canada, they have already received preorders from other countries. The U.S. has preordered the first 100 million doses, with option to add another 500 million. The United Kingdom has ordered 30 million. The companies also have a proposed agreement with the European Union for 200 million doses.

Source: CBC News website

Author:Emily Chung, Amina Zafar