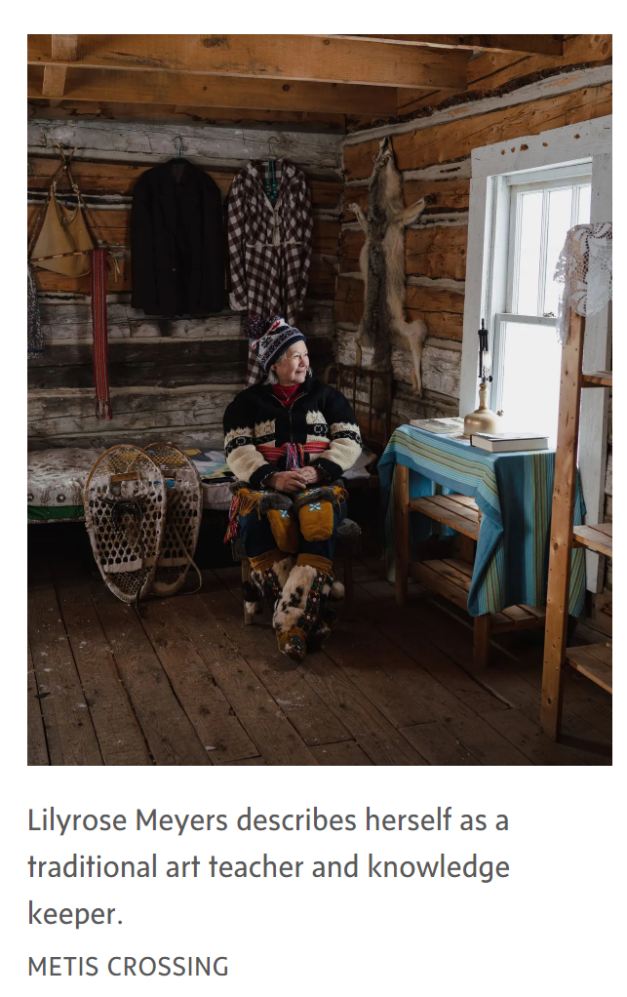

Needle and thread in hand, I sew two pieces of pink flannel together, my blanket stitch tight and careful. My instructor, Lilyrose Meyers, who describes herself as a traditional art teacher and knowledge keeper, stands watch at the front of the room.

“I don’t have two cultures, I have many cultures,” she says, gesturing to Métis capotes (jackets) decorated with intricate beadwork, an art form with origins in both Indigenous and European cultures.

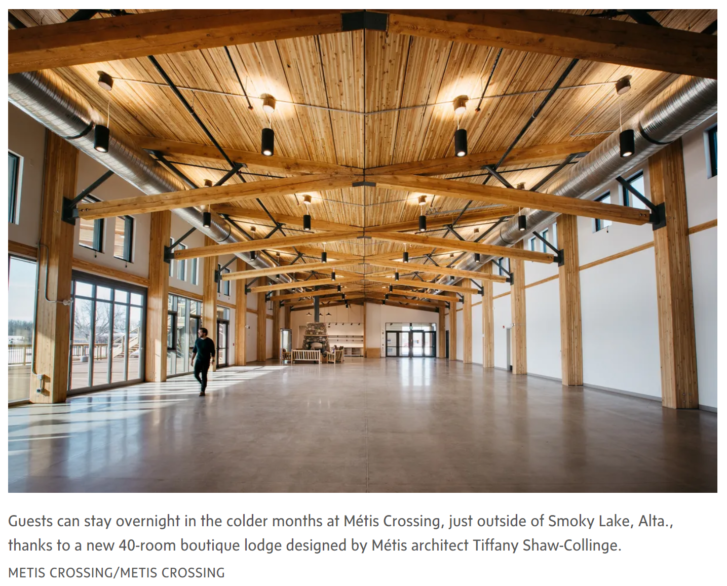

My mom and I have travelled to Métis Crossing, just outside of Smoky Lake, Alta., to learn how to make gauntlets (mittens). It’s one of the many new winter workshops being offered at the cultural centre, marking its transition to a year-round destination. Guests can stay overnight in the colder months, thanks to a new 40-room boutique lodge designed by Métis architect Tiffany Shaw-Collinge.

But we’re not just here to make mittens or even to check out the new hotel. We’re here because we have questions.

“I don’t fully understand what ‘reconciliation’ means,” admits my mom in the days leading up to our visit.

It’s not for lack of trying. A history buff, she’s read countless books written by Indigenous authors, including Buffalo Days and Nights by Métis fur trader Peter Erasmus. I’ve seen her do the work of grappling with her own power and privilege. And yet, she’s still searching for this piece of the puzzle.

According to Juanita Marois, chief executive of Métis Crossing, bridging this uncomfortable gap is just part of the reason the cultural centre exists.

“This is a place where Métis people can see the very best of their culture,” Marois says. “But it’s also a safe place to ask difficult questions and to interact with Métis people on a peer-to-peer basis.”

For Indigenous tourism operators in northern Alberta, tourism isn’t just about providing visitors with memorable holidays. It’s a tool for reconciliation.

Marois points to the example of Métis Crossing’s new 320-acre wildlife park, where bison (or “bufloo” in Michif, the language of the Métis) were introduced in September, 2021. The park is the result of a partnership with a non-Indigenous neighbour, rancher Len Hrehorets.

“For us, reconciliation is about the day-to-day of how Indigenous and non-Indigenous people build business and promote culture together,” Marois says.

When Hrehorets arrives to pick us up for our wildlife tour in his half-tonne truck, he’s got his cowboy hat on and the local country station playing. The story we hear over the next hour isn’t just about his acquisition of rare white bison, it’s also about how bison hunts were critical to the development of Métis nationhood. “Everything I’ve learned about the Métis nation, I’m excited to share,” he says.

Across the region, other tourism operators are also sharing their knowledge. In Edmonton, Métis geologist Keith Diakiw offers geo-hiking tours of Elk Island National Park and the River Valley with Talking Rock Tours, a company that he started “in the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission findings,” he says. About an hour north of Edmonton, Métis homesteader Natalie Pepin runs ReSkilled Life, which focuses on reclaiming traditional skills such as hide tanning, and helping youth connect with their heritage.

And last year, Fort Edmonton Park unveiled the Indigenous Peoples Experience (IPE). Part of the park’s $165-million renovation, the 30,000 square foot exhibit was created in consultation with the Métis Nation of Alberta and the Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations. The first exhibit of its kind in Canada, it showcases the perspectives of the area’s Métis and First Nations people, told in part through sound and video installations. Bison stampede past on the walls, stories are shared in a tipi and at the centre of it all, the North Saskatchewan River flows underfoot

The IPE had been more than a decade in the making. Yet, when it opened its doors in July, 2021, any celebration was subdued. Just over a month had passed since the remains of 215 children were found at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

“It brought back all of that grief,” says IPE interpreter Naomi McIlwraith, an educator and poet of mixed Cree, Ojibwe, Scottish and English heritage. “But when Indigenous people come in, they’re overwhelmed beyond words because the story is finally being told from their perspective.”

Like Marois, McIlwraith believes that tourism has a powerful role to play in reconciliation, partly because of its capacity to reach large audiences. During the summer, the IPE received up to 2,000 visitors a day. People are “hungry” right now, says McIllwraith, for the opportunity to ask questions without judgment. Residential schools are a frequent topic of conversation (and the focus of a film in the exhibit), but interpreters also share traditional Cree, Dene, Anishinaabe, Nakota and Blackfoot teachings.

The message in the IPE’s entry space is “wîci-pimohtêmin. It’s Cree for ‘walk with me,’” says McIlwraith. “Together, we’ve arrived in this place – and together, we can move forward.”

At the end of the gauntlet workshop, after everyone has filtered out into the cold night, we stay behind. Meyers joins us at our work table, where she demonstrates how to tuft moose hair using a piece of yarn. I watch as my mother and Meyers, nearly the same age, stitch and chat about their respective rural upbringings and their continuing sewing projects.

Together, they walk.

The writer was a guest of Explore Edmonton. It did not review or approve this article prior to publication.

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: JESSICA WYNNE LOCKHART