As of Monday, you can travel across the U.S. border — and around the world — if you’ve been vaccinated against COVID-19.

But is there a way to inoculate yourself against the menace of mass tourism when it makes a full comeback?

Since early last year, most of us have been grounded, suffering from Groundhog Day syndrome until the pandemic ebbs. With airplanes parked and hotels empty, it has long felt like the end of travel.

Global tourism plunged by more than 1 billion visits last year. But it’s merely the calm before the comeback.

Pre-pandemic, tourism kept climbing inexorably — from 400 million visitors in 1990 to 1.4 billion in 2019. It was an unsustainable trendline, leading to overcrowding and overkill.

It will only get worse, post-pandemic, when those missing billion travellers find their way back. Is there a way to avoid the suffocating contagion of mass tourism when the numbers surge again?

The pandemic may be the perfect time to rethink how we travel to the ends of the earth to get away from it all, only to find ourselves surrounded and suffocated by our fellow travellers.

Per capita, Canadians are among the world’s most active travellers, close behind the British. Snowbirds aside, vaccinated Canadian groundhogs will be back to beaching themselves in the Caribbean once the coast is clear.

But what’s really driving the growth curve is the emergence of China — not just as an irresistible tourism destination, but an unsustainable source of outbound tourists.

When I took over the Star’s Asia Bureau two decades ago, about 10 million Chinese took overseas trips every year. Before COVID grounded everyone, the Chinese were taking 155 million trips abroad — a 15-fold increase that was increasing by 15 per cent a year.

That makes China the biggest single source of outbound travellers in the world today. Domestic tourism is also surging, with more than 5.5 billion internal trips a year.

Historically, the Chinese have been inveterate travellers and wanderers. Today, they just want to get away from it all, by escaping the tourist congestion and reconstruction at home.

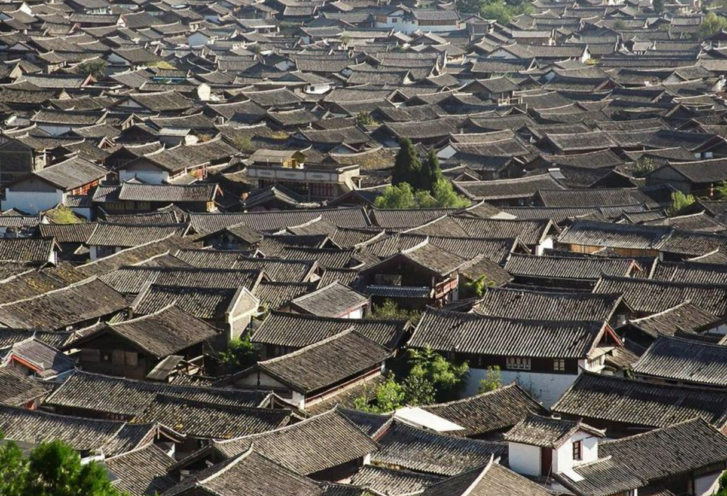

I saw that when I travelled to the remote the village of Lijiang to write about its UNESCO World Heritage Site in Yunnan province. Considered the inspiration for Shangri-La, it’s now Paradise Lost — because the Chinese have torn down authentic homes in nearby villages to make way for new shopping malls and hotels, owned and operated by outsiders.

It’s the same story across China, where ancient temples are being suffocated by modern commercial sprawl and historic neighbourhoods are demolished or displaced by swank new restaurants. And so what you see becomes an optical illusion.

We fantasize about going to a religious sanctuary, or a sumptuous palace or an isolated village where we can be alone with our thoughts. As tourism infiltrates the far corners of the globe, the travel juggernaut seems unstoppable — and increasingly unmemorable.

And the Chinese are coming — just like the Americans and the British and the Japanese before them — but in bigger numbers that are ever more disruptive. That’s especially true when they go in search of unspoiled destinations like neighbouring Myanmar (formerly Burma), which is a case study in over-tourism.

By far the largest share of Myanmar’s tourists now come from China — and at a breathtaking pace: 300,000 visitors arrived in 2018, more than doubling a year later to 750,000 Chinese (until COVID intruded).

The tourist invasion has caused culture shock for Myanmar, a country isolated for decades. The Chinese government responded with an illustrated guidebook on “Civilized Tourism,” instructing its travellers to respect local customs, cultural traditions, religious beliefs and the environment.

“We should educate our citizens to be civilized when travelling abroad. Don’t litter water bottles; don’t destroy their coral reef. Eat less instant noodles and more local seafood,” President Xi Jinping admonished them publicly.

The bigger problem is not the misbehaviour but the missed opportunities for impoverished Myanmar. The economic chimera of Chinese tour groups is caused by “zero-dollar” tourism — whereby almost everyone comes on a prepaid package tour, with all the cash flow going to a Chinese-owned travel agency, hotel, restaurant and souvenir shops — squeezing out local operators.

Chinese tour groups are not necessarily the worst offenders, merely the latest arrivals. After all, everyone mocked the Ugly American in Paris years ago and many still do.

It’s not about nationalities but numbers. It’s a question of the capacities of locals to absorb the onslaught — and the sensibilities of foreign travellers who find themselves surrounded by fellow tourists from home, despite trying so hard to get away from it all.

The numbers are no less daunting when you look at the wave of towering cruise ships that deliver factory tourism on the high seas. These floating hotels are up to 18 storeys high, boasting as many as 6,000 passengers who are disgorged all at once on port cities — leaving the locals drowning in day-trippers who leave few scraps behind when they clamber back aboard for the night.

Taken together, these trends will be unstoppable unless we stop and think about how to see the world differently. There are no magic solutions to restore the mystery or fantasy of foreign travel, but there are certainly ways to reduce the misery of monster tourism before COVID removes all constraints.

I’ll be sharing some of those ideas in a public talk on “The End of Travel — Time to Revisit Mass Tourism,” at Ryerson’s Chang School (free advance registration) via Zoom on Tuesday, and in future columns. Stay tuned, stay safe, and safe travels.

Article From: The Star

Author: Martin Regg Cohn