At first glance, Manitoba’s COVID-19 vaccine program is moving along at a rapid pace. About two-thirds of adults have already received at least one dose and that rate has been climbing steadily. The province is now accepting bookings for second doses.

But the top-line number hides a troubling dynamic that could make it difficult for Manitoba to achieve the widespread vaccine coverage health officials are aiming for: Demand is slowing, especially for younger age groups, and some communities, particularly in rural areas in the southern part of the province, are lagging far behind.

Joss Reimer, the medical lead for Manitoba’s vaccine task force, says it means the province will need to change tactics to push up its vaccination numbers even further. She also acknowledges that hesitancy or outright hostility toward vaccines may prevent some communities from ever achieving high enough rates of immunity to keep COVID-19 at bay.

“We are getting to the point now where we’re starting to see that slowdown beginning,” Dr. Reimer said.

“I’m sure there are some areas that won’t reach the levels that we want, and that makes me incredibly worried.”

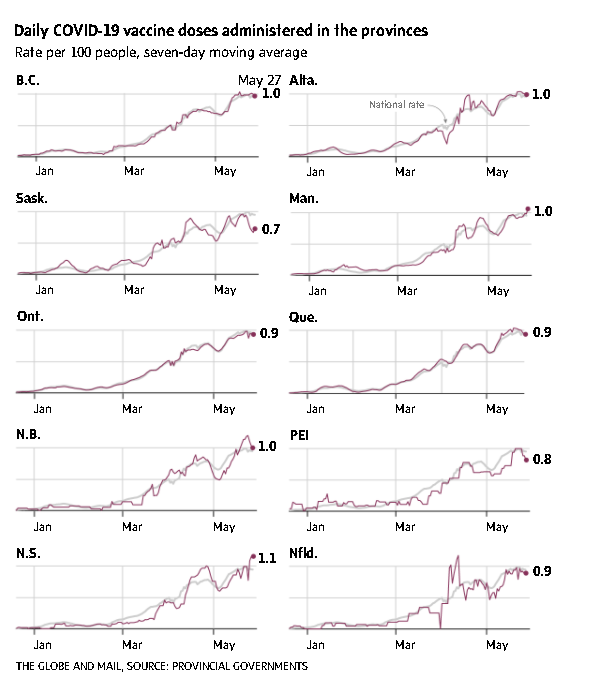

The initial months of Canada’s vaccine rollout have been defined by stories of people scrambling to find scarce doses: An unannounced vaccine clinic in B.C.’s Fraser Valley that drew hundreds of people to an athletic park, where they stood in line for hours; a 32-hour marathon clinic in Ontario’s Peel Region that drew thousands; phone lines and online booking systems that collapsed under the demand as each new group became eligible.

But in coming weeks, as provincial vaccination campaigns get through the most eager and willing recipients, health officials are expecting the pace of vaccinations to slow, leaving governments to figure out how to reach the people who, for whatever reason, have not signed up for a shot even as eligibility in most places has opened up to pretty much everyone.

For Manitoba, Dr. Reimer said the response depends on who has not been vaccinated and why. In some neighbourhoods of Winnipeg, where language barriers, work schedules and long-standing social inequities have made it difficult for some to get the shot, she says the focus needs to be on breaking down those barriers.

In some rural areas where the main issue appears to be attitudes toward vaccines rather than access, she says health officials are meeting with religious leaders and engaging prominent members of local communities to confront skepticism and misinformation. The overall vaccine rates in southern Manitoba are about 39 per cent and a lot lower in some places, such as the area in and around the small community of Stanley near the U.S. border, where just 12.5 per cent have received a single dose.

“We know that this is not going to be a quick fix,” she said.

About 62 per cent of the adult Canadian population had received at least one shot as of May 22, according to the federal Public Health Agency website, and overall, the number of Canadians who say they intend to be vaccinated has increased since last fall.

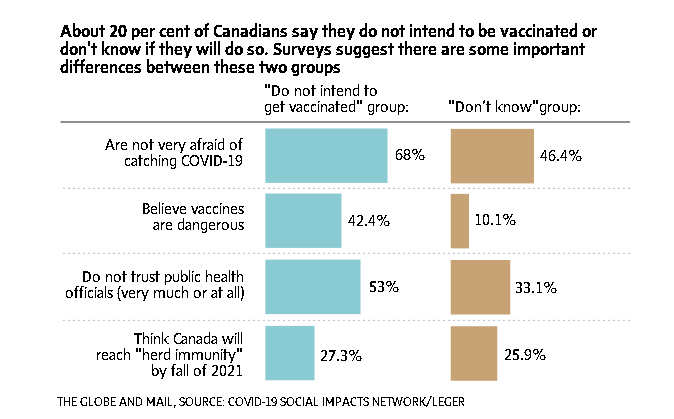

The trend is evident in a series of weekly polls conducted by Leger on behalf of a research project called the COVID-19 Social Impacts Network. When the polling began last October, 60 per cent of those who responded said they intended to get vaccinated while 20 per cent said they would not and another 20 per cent said they were not sure. By April, that split was 80 per cent, 10 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively, and it has largely remained there.

The surveys, which are conducted weekly, are based on responses from a representative group of 1,500 Canadians.

This month, the poll has included questions aimed at better understanding the differences between the “no” and “I don’t know” groups. The answers reveal that most of those who do not intend to get vaccinated are the least afraid of COVID-19, most convinced that vaccines are dangerous and most distrustful, by far, of public-health officials.

In contrast, about one-third of those who are not sure about their intentions are at least somewhat afraid of COVID-19 and only about 10 per cent do not trust vaccines. And despite their hesitancy, only one-third say they do not trust public-health officials a lot or at all.

Eve Dubé, a medical anthropologist with Quebec’s National Institute of Public Health, has found similar results among respondents in a weekly survey she has conducted in that province.

While Quebec appears to be doing somewhat better than Canada as a whole in its percentage of those who intend to get vaccinated, the challenge appears to be greatest among 25- to 40-year-olds, a quarter of whom fall into the category of hesitant, Dr. Dubé said. In this group, the influence of peers could be especially important for shifting attitudes.

“When most people around you are getting vaccinated or have been getting their appointment, that has an impact on you,” she said.

Not every province is releasing detailed information about who is being vaccinated, but in places that are, significant gaps are immediately apparent.

In B.C., for example, vaccination rates are generally higher in the southern half of the province and cities such as Vancouver, and lower in the rural areas in the north. Alberta has a similar urban-rural divide, with the highest rate of 66 per cent in the Twin Brooks area of Edmonton and the lowest in High Level in the province’s northeast, where about 13 per cent of people have had a single dose.

In Toronto, a report released by the Wellesley Institute last month found that vaccination rates were lowest in neighborhoods with the lowest incomes and highest proportion of people who identify as visible minorities.

Raywat Deonandan, an epidemiologist and associate professor at the University of Ottawa, said holdouts can generally be divided into three groups: people who are apathetic, or have logistical challenges accessing the vaccine; those who are still hesitant or skeptical; and “hardcore anti-vaxxers.”

The first group can often be reached with mobile clinics and other outreach efforts. A portion of the remainder could be swayed by targeted public education campaigns, while some will steadfastly refuse. And some can be persuaded into getting the jab through lotteries, gift cards or other perks, a strategy that has been successful in some U.S. states and is being considered in Manitoba and Alberta.

Article From: Globe and Mail