This post is also available in: 简体中文 繁體中文

Some suspect the science. Some don’t think they’re vulnerable. And some just don’t trust government messaging.

Canada’s vaccine campaign has been crushing it lately, with an impressive 80 per cent of eligible Canadians having had at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

That statistic distracts from a troubling fact, however: more than six million Canadians still haven’t had a shot, just as experts are warning we need more coverage to beat back a possible surge of cases in the fall.

The first-dose vaccination campaign now seems to be grinding to a halt, with fewer than 50,000 people getting a vaccine each day — down from a peak of over 185,000 last month — even though those doses are now readily available nationwide.

CBC News has spoken to some unvaccinated Canadians to learn more about the hesitancy that has taken hold in some pockets of the country.

Many of the holdouts say they’re concerned about safety and side effects. Others say they’re not happy with the current products on offer.

There are also practical considerations. A number of the unvaccinated have a needle-related phobia that can make getting a shot a frightening experience. Some have severe allergies to the vaccine components. Some rural Canadians have had trouble with access.

And experts also suggest somewhere between two and 10 per cent of the population is vehemently opposed to vaccines — no matter what public health officials say about the many benefits of getting a shot.

Nadina Smith graduated from teachers’ college this spring and she’s feeling the pressure from family and friends to get a shot before school starts up in the fall.

Smith, who is from Alberta, told CBC News she’s researched the science behind various COVID-19 vaccines and she’s most comfortable with the one-dose Johnson & Johnson shot, which uses the more conventional viral vector vaccine technology.

Such vaccines use a modified version of a different virus (the vector) to deliver instructions to cells, and are widely used to prevent infectious diseases like influenza.

New tech vs. old tech

Canada ordered the J&J shot — 300,000 doses were delivered months ago — but there are no plans to use it as part of the vaccination campaign. Government officials have said the provinces and territories have shown no interest in obtaining this product.

“I know the traditional vaccines aren’t rated quite as effective in the research — but I’m comfortable with that style. I would happily go at this very moment to get that,” Smith said.

While the mRNA products produced by Pfizer and Moderna have been deemed safe and effective by Health Canada and other regulators after a careful review of clinical trial data, Smith said she’s still reluctant to accept a vaccine that was developed so quickly.

She said she’s not opposed to vaccines (she describes herself not as “vaccine hesitant” but as “mRNA vaccine hesitant”) but she’s concerned about the possible long-term effects of mRNA shots in particular, which use relatively new technology.

‘I don’t want to be the guinea pig’

“How do we know what kind of impact this is going to have on our bodies? Am I gonna have a third eye in 20 years?” she said.

“I mean, I know I’m not gonna have a third eye, but I’m just trying to explain what I mean. We don’t know what the potential outcomes are in the long term.

“The only thing that would have swayed me is if there was some sort of research or study of the long-term effects of COVID mRNA. For me, that is a huge concern and I don’t want to be the guinea pig.”

Messenger RNA, or mRNA, directs protein production in cells throughout the body to trigger an immune response and protect against infectious diseases.

While an mRNA vaccine has never been on the market until now, mRNA vaccines have been tested in humans for at least four infectious diseases: rabies, influenza, cytomegalovirus and Zika. No long-term side effects from those products have been reported.

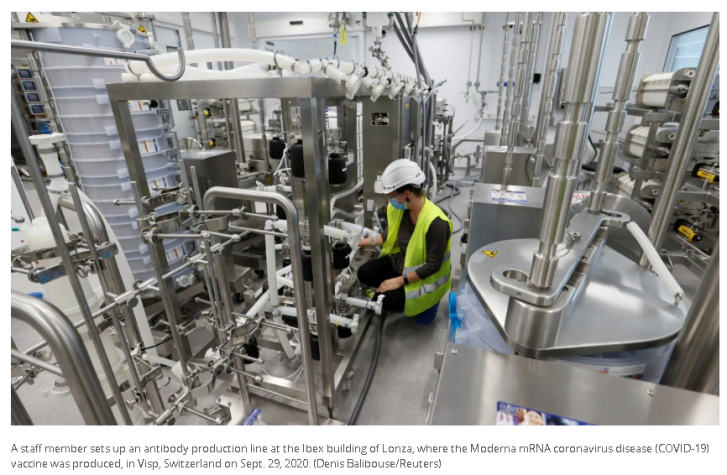

Researchers have been studying mRNA technology and its potential for three decades. With an injection of hundreds of millions of dollars in emergency funding from the U.S. government and other sources, companies like Moderna and BioNTech (and BioNTech’s partner Pfizer) turned a promising piece of molecular biology into a usable product that has been deployed in several hundred million people to great effect.

Mixed messages

Lorie Carty, a retiree from Prince Edward County, Ont., said the actions of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) and Health Canada — two bodies that have sometimes offered competing advice about vaccines, most notably about the AstraZeneca product — have made her question the safety of the vaccines.

“It seems like they’re flying by the seat of their pants, trying to figure things out as they go along and there’s just so much mixed information,” Carty said of federal health officials.

She said she has an appointment booked but she keeps rescheduling because she’s just not ready to commit.

“I want to be sure before I put that in my body because once it’s in there, there’s no going back,” Carty said.

“I’m not saying I’m an anti-vaccine person. I just don’t have enough confidence. We really don’t know the long-term effects. There’s just so many questions and every day you read something different.”

Andriy Petriv is a long-haul truck driver from the Toronto area. He said he and his wife got sick with what they think was COVID-19 shortly after Christmas. While they didn’t get tested, Petriv said they had all the usual symptoms.

‘I just don’t see the point’

To satisfy his curiosity, he said, he recently had an antibody test to see if he had developed any immunity to COVID-19. The test, which is used to determine past infection, showed that he had developed some antibodies to the virus.

“Since I already had it, I don’t see the point of taking a vaccine. It could be dangerous in some cases and given the fact that I already have antibodies, why should I even take a risk?” he said in an interview.

“If I have to take it, I’ll take it. I’m not scared of vaccines. I just don’t see the point. Why put something in my body just to have a certificate or something? If you’re not thirsty, why should you drink just to make somebody happy?”

He said he’s also disturbed by the fact that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has so far only granted the COVID-19 vaccines an emergency use authorization, not “full approval” — a process that can sometimes take years. The FDA has said full approval is coming.

Health experts maintain that even people with past infections should get a vaccine. Some jurisdictions, however — including Quebec, France, Germany and Italy — have been administering just a single dose to anyone with a confirmed previous diagnosis.

“While you will receive some immunity from having a previous infection, it remains unclear the duration and breadth of that immunity,” said Dr. Kumanan Wilson, a professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa.

“It’s uncertain whether being exposed to a previous version or variant of the virus will protect you against new variants as strongly as a vaccine will.”

Vaccine acceptance is growing

Shannon MacDonald is an associate professor in the faculty of nursing at the University of Alberta. Before the immunization campaign got underway, she conducted a study on the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines among the Canadian population.

She found that, in general, the vast majority of Canadians are not diametrically opposed to vaccines. In fact, fewer than 2 per cent of Canadian parents refuse childhood shots for their kids.

Knowing little about the shots that would soon be deployed, 65 per cent of Canadians polled for MacDonald’s study said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as Health Canada approved one for use — a figure she described as “hugely encouraging.”

The number of willing vaccine recipients has grown steadily since that study was published.

“Unfortunately, the small proportion are quite vocal and there’s a perception that they’re bigger than they are. I think focusing on people who have really legitimate questions — and when I say legitimate questions, I don’t mean their concerns are necessarily based on facts — is really key,” MacDonald said in an interview.

‘Breakthrough cases’ extremely rare

MacDonald said the best way to convince the hesitant is to show them the data on just how effective the vaccines have been at preventing infection.

For example, of the 403,149 COVID-19 cases reported in Ontario between December 14, 2020 and July 10 of this year, just 0.4 per cent were so-called “breakthrough cases” — COVID-19 infections in people who had received their second doses 14 days prior.

About 4 per cent of all cases reported in that seven-month period were people who were partially vaccinated with just one dose. The rest, of course, were unvaccinated.

As of July 10, fewer than 18,200 of the 10,000,000 people who have received at least one dose so far in Ontario have contracted the virus — 16,358 were infected when they were only partially vaccinated and 1,765 became infected after having two doses.

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control estimates that 97 per cent of the people who have been admitted to hospital recently with COVID-19 are unvaccinated.

The trust factor

MacDonald said the very low number of adverse effects should also assure the hesitant that these products are safe.

“The safety profile has been impressively good,” she said. “You could put the message on a billboard and that might reach some people, but for people who are distrustful of the government, pharmaceutical companies, whatever, they need to hear the message from people that they trust. We have to get the message out there.

“All it takes is one case in your unvaccinated community and you’re all at risk.”

According to Public Health Agency of Canada data, there have been only 2,222 serious adverse events reported post-vaccination in Canada as of July 9. That’s just 0.005 per cent of all doses administered.

Despite these positive indicators, MacDonald said the vaccination campaign will almost certainly hit a wall of entrenched hesitancy.

A fourth wave of cases might convince the unconvinced that they’re better off with a shot, she said. “You’d hate to wait to see an outbreak to say, ‘See this is what could happen.’ But that might be the case.”

She said public health authorities should still try to persuade some of the unvaccinated but, at a certain point, those energies might be better spent on getting the partially vaccinated back for that crucial second dose.

“Let’s focus on them instead of jumping through one hundred hoops to try and get a first dose into people who aren’t interested,” she said.

Article From: CBC

Author: John Paul Tasker