Bruce Anderson: Compared to the vaccinated, the vaccine hesitant don’t have a lot of trust in government. They also try to avoid prescriptions, dislike putting anything unnatural in their bodies and say they are reluctant to take any vaccines. Most worry that COVID-19 vaccines haven’t really been tested for a long time.

If science is right, and I for one trust it, we’re rounding the final corner of this pandemic, at least in terms of the things we can do in Canada to keep ourselves safe. While it’s unlikely that we will stumble, every day we see examples of how we could.

I recently read a story about a conservative hotline radio host known for vaccine scepticism. Just before COVID-19 killed him, he told people he made a mistake not to get vaccinated.

How does this happen in an advanced society, we ask ourselves? How do some read that today’s infections are almost exclusively happening among the unvaccinated — and still think it’s a bad idea to get the jab? How can parents have any doubt about whether their kids’ teachers should be vaccinated?

Since vaccines against COVID-19 first came into view last fall, our team at Abacus Data has been studying public opinion about getting vaccinated. After more than 30,000 interviews on the subject here’s where we stand; all of our work has been shared as a contribution to a coalition of organizations working together to help promote vaccinations.

Based on an adult population of 29.5 million in Canada, our latest results show 7 percent or 2.1 million adults are hesitant and the same number are outright refusing a COVID-19 vaccination.

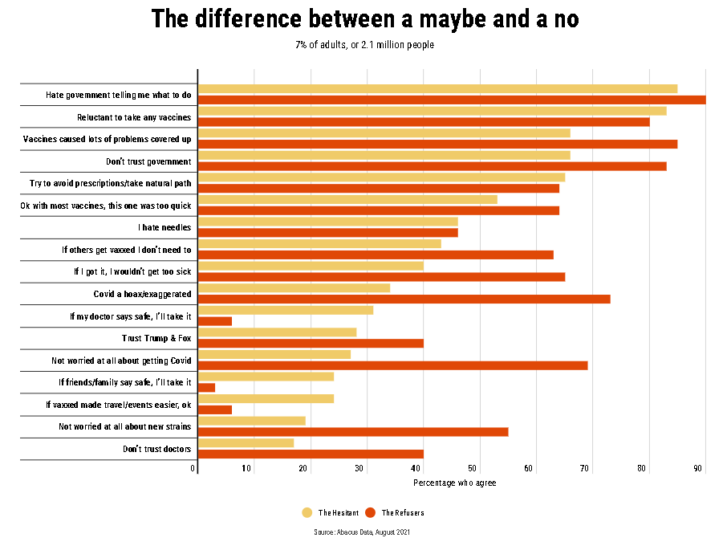

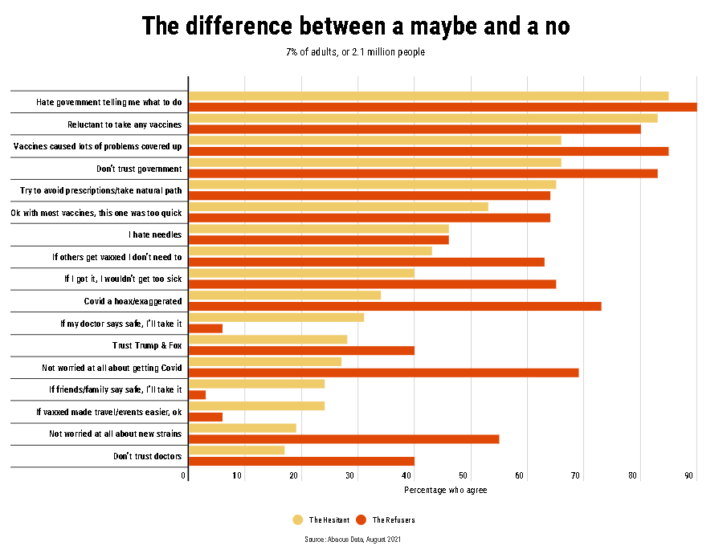

Understanding how to increase vaccine acceptance starts by acknowledging that the hesitant and refusers share some similarities, but in other respects are quite different.

Let’s start with the “vaccine hesitant,” people who say they’re “willing but would rather wait a bit longer,” or “would rather not but could be persuaded.”

The number of vaccine hesitant is a lot smaller today than it was a few months ago, and chances are good it will be smaller still in a month’s time. But while hesitancy dropped from 21 percent in May to 7 percent today, the last few weeks are slower going.

Still, based on the attitudes of the hesitant, there’s a good chance we will hit 90 percent of adults fully vaccinated — and possibly even a point or two higher than that.

The hesitant are not conspiracy theorists. They aren’t angry at the world. They don’t think COVID-19 is a hoax. They aren’t radicals of the left or the right — 61 percent of them say they are on the centre of the spectrum. Two thirds have post-secondary education. They might be timid, but they’re not stupid.

Almost half of them (46 percent) live in Ontario and well over half of them (59 percent) are women. A quarter were born outside Canada. Their average age is 42 and the plurality are between 30 and 44 years old. If they were voting in a federal election today, 35 percent would vote Liberal, 25 percent Conservative, 17 percent NDP, 9 percent Green — pretty similar to overall voting intentions for the entire population.

However, compared to the vaccinated, they don’t have a lot of trust in government. They also try to avoid prescriptions, dislike putting anything unnatural in their bodies and 83 percent say they are reluctant to take any vaccines. Most worry that COVID-19 vaccines haven’t really been tested for a long time.

Just under half hate needles and 43 percent believe that if others get vaccinated they don’t need to.

A third say their doctor could persuade them and a quarter say friends and family can. A similar number say they will get vaccinated if it makes attending events and travelling easier.

In short, many of the hesitant lack confidence in government and vaccines but are still signalling that the right messages, information, and incentives will make them decide to be vaccinated.

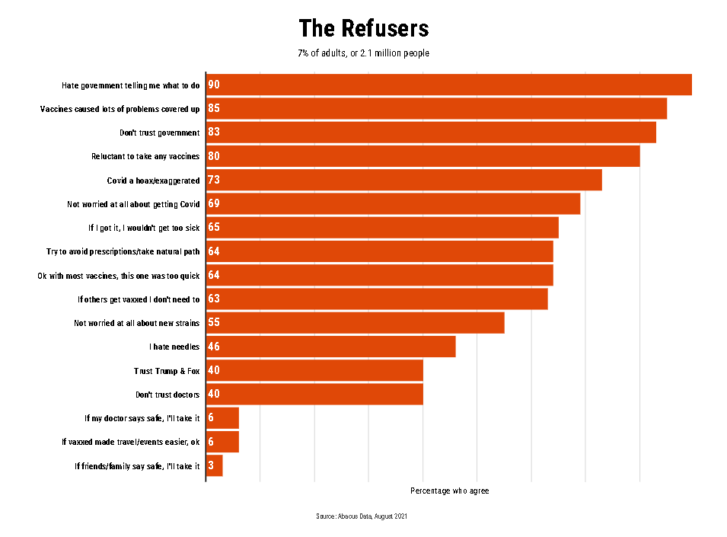

Vaccine refusers are a different situation. They are unhappy with the direction of the world, and of Canada.

Three quarters (73 percent) of them think COVID-19 is a hoax or greatly exaggerated, while only 33 percent of the hesitant buy that argument.

Two thirds of them (69 percent) don’t worry at all about getting COVID-19 (only 27 percent of the hesitant feel this way). Two thirds (65 percent) say if they got COVID-19 they wouldn’t get really sick (only 40 percent of the hesitant agree).

Forty percent of refusers don’t trust doctors, while only 17 percent of the hesitant feel that way. Most Canadians don’t trust Donald Trump or Fox News, but the more they do, the more likely they are to avoid getting vaccinated. Among the fully vaxxed, 11 percent trust Fox and Trump compared to 28 percent among the hesitant and 40% among the refusers.

There are some similarities within the hesitant and the refuser groups. More than 85 percent of both groups hate the idea of government telling them how to live their lives. The hesitant and refusers are equally likely to try to avoid any prescriptions and vaccines, preferring to rely on their body’s natural defences.

So where does this leave us?

Most refusers will probably not be vaccinated unless being unvaccinated becomes too costly or inconvenient. If they haven’t been scared by the disease by now, they won’t be. If they haven’t been persuaded by peers or medical professionals by now, that probably won’t change. Only 6 percent say that their doctor could change their mind, only 3 percent say a friend or family member could.

Most of the hesitant may be vaccinated at some point this year. For some, especially those with unique cultural group perspectives or health anxieties, the diligent work being done by public health agencies and vaccine outreach teams like This is Our Shot or 19 to Zero is making a difference. Even if the pace seems slow to everyone else, the work is essential, and working.

Some of the hesitant will respond to rewards and draws for prizes, but others may need firmer, more clear cut and persistent nudges to see being unvaccinated as a limitation on the experiences they used to enjoy, or that vaccinated people can return to. That remaining unvaccinated carries a cost, and possibly a stigma, as vaccinated people look at them as free riders unwilling to do their part to protect the community, the economy — and Canada’s children for whom a vaccine is not yet on offer.

I’m not encouraging polarization; it already exists and the weight of the judgment of the majority will be felt among the 7 percent.

Vaccination of Canadians against COVID-19 has placed in stark relief some of the most important distinctions between the U.S. and Canada when it comes to political culture. Most Canadians placed faith in government to navigate a way through this pandemic, while America reminded us how deep and broad a dislike of government involvement is in their culture.

Our media offered some strange takes but nothing that resembles the role played by conservative talk radio, or Fox News and its similarly styled media platforms.

We’ve got a party leader who is against masks and vaccines, but he’s the one who couldn’t win a single seat anywhere in the country, including the seat he had held for years. America is chock a block with politicians who are pushing laws that encourage COVID-19 insanity.

After immersing in this subject for almost a year and digesting more data on this than on any other single subject in my almost 40 years in the polling business, count me as an optimist, both about where we will end up in terms of vaccinations and our ability to (mostly) rally together.

It hasn’t been perfect, lives were lost that didn’t need to be, the psychological strains will be lasting and millions suffered economically. But if it helps to compare to the alternatives there are plenty of ways this could be going worse.

For the refusers, it seems to come down to a profound lack of trust in government, doctors, vaccines and the direction of the world. For the hesitant, it’s more a question of confidence building and in some cases nudging with messages, incentives and infringements on the flexibility of life as an unvaxxed person.

Bruce Anderson has been a prominent pollster, communications counsellor and political analyst in Canada for many years. Earlier in his career, he worked on election campaigns for both the Progressive Conservatives and the Liberals, but does not work for any political party now. For several years he was a regular member of CBC’s popular At Issue panel, and currently does two podcasts,“Good Talk” with Peter Mansbridge and Chantal Hebert and “Smoke Mirrors and the Truth” every Wednesday on Peter Mansbridge’s The Bridge podcast. He is the chairman of Abacus Data and Summa Communications and a partner in Spark Advocacy. He is co-chair of the volunteer initiative Faster Together which is working with more than 270 organizations across the country to promote vaccinations against COVID.

Article From: Maclean’s

Author: Bruce Anderson