‘Everyone’s frantically trying to find places,’ says incoming University of Victoria student

Some Canadian universities are turning down residence applications by the hundreds this year, and the rejected students — who were hoping for an on-campus experience after the COVID-19 pandemic ate their final years of high school — say it’s a major disappointment. Many say they’re struggling to find alternative housing.

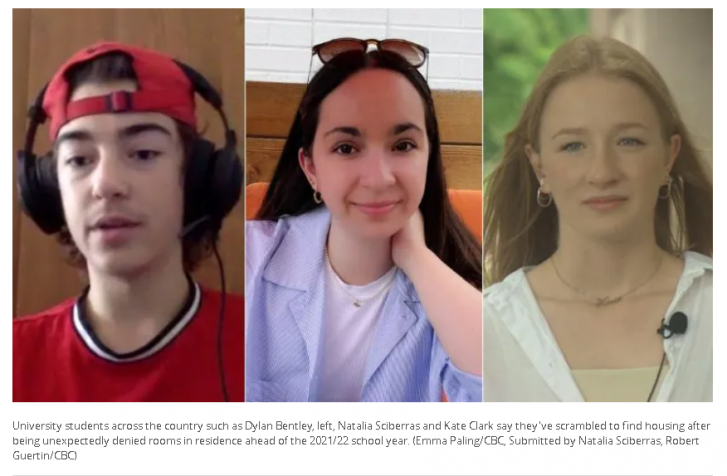

“It was a little bit stressful that it had to happen like that,” said Dylan Bentley, a 17-year-old incoming first-year student at the University of Victoria. “The whole situation kind of sucks.”

He and his parents are now looking for a rental in Victoria remotely from Metro Vancouver. Bentley said he may have to quit his job and move on short notice if he signs a lease that begins Aug. 1 or Aug. 15, if nothing for Sept. 1 is available.

“As of right now, it’s really hard to find a place [because] I guess everyone’s frantically trying to find places there.”

Another student, Danica Thomas, who is going into her second year in biology at the University of Victoria, said the university should have done more to prevent this from happening.

“If I had known that even one undergrad getting a placement would have such a slim chance, I probably would have transferred to a different school for this year,” the 19-year-old said in an email to CBC.

“It is a highly confusing and frustrating time,” she said, but she’s looking for off-campus housing and holding onto the hope that she’ll be eventually offered a residence spot.

She said if she can’t find housing close enough to campus, she’ll have to bring her car and pay thousands of dollars for insurance, which she hadn’t planned for.

Hundreds deferred offers last year due to pandemic

The University of Victoria says the crunch is happening because the pandemic has led to a jump in enrolment and there are hundreds of students who deferred last year who now want to live in residence. The school also removed two old residence buildings in order to start building a new residence and dining facility.

UVic received 2,500 applications for 2,100 rooms this year, Jim Dunsdon, associate vice-president of student affairs, said in an interview with CBC News.

“When times are incredibly tight, as they are now, I can understand why parents and students are anxious and are concerned about that.”

Dunsdon said students who applied this year were aware that there was no longer a housing guarantee for first-year students, and that rooms would be assigned by a lottery. The school prioritized students who deferred their offers last year because they applied when residence was still guaranteed for incoming students.

He said students weren’t told how many spots would be available when they applied for the lottery, because the school didn’t know what capacity COVID-19 restrictions would allow.

Students at other universities, such as Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., and Dalhousie University in Halifax, are in the same boat.

A spokesperson for Queen’s said in an email that it received 4,700 applications for 4,140 spots. The school’s residences will operate at 93 per cent of the typical capacity this year, as triple, quad and loft double rooms will no longer be offered, and some spaces will be left for isolation.

Higher demand

A spokesperson for Dalhousie did not say how many applications it turned down when asked by CBC in an email, but said the school is seeing higher demand than usual, especially from upper-year students who studied remotely last year.

Dal has reduced capacity to 80 per cent because of COVID-19, housing only one student in rooms that usually house two and leaving space for people who have to quarantine or self-isolate, the spokesperson said.

Other institutions say they’ve met demand by increasing capacity and requiring COVID-19 vaccinations to live in residence.

Natalia Sciberras is starting her first year at Queen’s in September. She said she had a panic attack when she found out she wasn’t being offered a spot in residence, especially because she’s moving to Kingston from Brantford, Ont., which is more than 350 kilometres away.

“When I tell you my heart jumped out of my chest, that would actually be an understatement,” the 18-year-old said in an interview with CBC.

“I’ve been waiting for this for years now, especially the past two, considering my high school experience was cut short, right? So, especially this past year, that was kind of my light at the end of the tunnel.”

Sciberras has since found an apartment with four other students, all of whom were also denied spots in residence. But she said she is still anxious about being left out of social activities for students who live on campus.

Vaccines required for U of T residences

The largest university in the country, however, says it’s seeing increased demand and still managing.

“We’re able to accommodate the first-year students who are wanting to live in residence,” Sandy Welsh, U of T’s vice-provost for students, said in an interview with CBC.

Welsh said the school is requiring students to get at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine before they move in, and to get their second dose as soon as possible. That means the school can allow students to safely live in double rooms, Welsh said.

U of T also has a new off-campus building that it will operate just like a residence, she said.

None of the other schools included in this story — UVic, Queen’s or Dalhousie — have mandatory vaccination policies for students living in residence. In addition to U of T, a number of other schools, including the University of Ottawa and Western University in London, Ont., have mandated vaccinations for students in residence.

The Canadian Federation of Students, a national organization representing 65 student unions, says this issue is bigger than any one school’s residence capacity.

“Across Canada, students and low-income individuals continue to face an ongoing housing crisis that has been exacerbated by the pandemic,” treasurer Marie Dolcetti-Koros said in an email.

She said that elected officials and schools have failed to help students and other renters, who are “being negatively impacted by a severe lack of affordable housing, the increased cost of living and an inability to earn a living wage.”

Kate Clark is one of the second-year students who was hoping to get a residence room at Dalhousie this year. She said she’s just as unfamiliar with university life as any first-year student because she stayed home and studied online last year.

“We don’t really know anybody. You don’t know the profs. You don’t know the area.

“So to get denied from residence and not have anywhere else to live downtown, it’s just a bad situation to be in because you’re just kind of left stranded and you don’t know what to do next,” she said in an interview with CBC.

At the time of the interview, she hadn’t found somewhere to live.

“It’s really hard to find housing downtown. And especially as someone who’s not from the Halifax area and I don’t know anyone here, it’s even harder to find accommodations.”

Article From: CBC

Author: Emma Paling