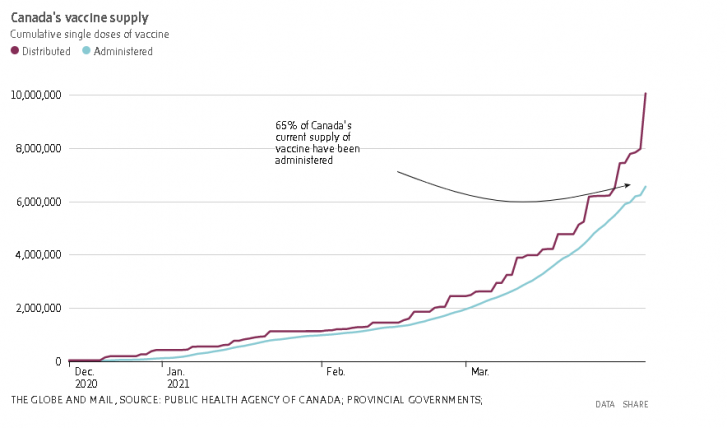

Just two thirds of available vaccine doses in Canada have been administered as provincial and territorial governments struggle to shift their COVID-19 vaccination programs into a faster gear after months of sluggish federal supply.

Most of the doses the provinces have not yet administered were only delivered since Saturday. But even before those shipments were added to the supply in local cold storage, vaccination campaigns faced challenges, including thousands of unfilled appointments, low vaccination rates among groups at the highest risk of COVID-19, and lack of certainty in deliveries.

Urgently fixing those issues is crucial as much of the country struggles with a third wave driven by variants of concern.

“On present course, the pandemic will blight the spring and shorten the summer for millions of Canadians,” said David Naylor, the co-chair of the federal COVID-19 Immunity Task Force.

The surge “cannot be contained without tough public health measures and a substantial acceleration of the current vaccine roll-out.”

Among the provinces, Newfoundland and Labrador has the slowest rollout of vaccinations, and as of Tuesday had administered only 54 per cent of available shots, with Manitoba and Nova Scotia tying for second last at 58 per cent, according to tracking by The Globe and Mail. Ontario had administered 63 per cent of its available doses, while Quebec administered 67 per cent. Saskatchewan leads the way at 78 per cent.

Alberta has administered 66 per cent of its shots and B.C. administered 69 per cent. On the east coast, P.E.I. and New Brunswick have delivered 64 per cent.

On Monday, Health Minister Patty Hajdu highlighted the discrepancies between the available shots and the number administered, but on Tuesday she and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau were careful not to directly criticize the premiers.

“We all need to speed up the vaccination process,” Mr. Trudeau said in French.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford said vaccine shipments are coming in “dribs and drabs,” and on Tuesday said more than 1.3 million appointments have been booked for the 1.4 million available doses. The province has said it can give 150,000 shots each day, but on Monday administered half that, 76,199. “Over the last few days, they just literally landed on our doorstep,” Mr. Ford said of the doses that arrived on the weekend.

The Quebec government is also facing criticism for the pace of vaccination. The province reached a peak of delivering 56,000 doses in one day two weeks ago, but hit a low of 22,600 Sunday – despite the arrival of more than 700,000 shots in recent days.

Over the Easter weekend, the United States administered more shots in three days than the 6.6 million Canada has administered in total since December.

Ms. Hajdu was not able on Tuesday to say how quickly the federal government expects provinces to administer vaccines once they receive them. The federal public health agency wasn’t able to provide data on how fast shots are being given, and neither were provinces such as Ontario and B.C.

That information is crucial to ensuring an effective vaccination campaign, Dr. Naylor said.

“You absolutely have to have a sense of your inventory and how fast it’s moving so that you can determine how sites are performing relative to the demand they’re facing,” he said.

New Brunswick takes between two and seven days to administer the shots once they arrive, government spokesperson Shawn Berry said. Nova Scotia is working in a two-week cycle from confirming supply to administering the shots, the province’s Chief Medical Officer, Robert Strang, said on Tuesday.

Quebec’s health department said administration of the shots begins four days after they arrive, but didn’t provide an upper limit for how long it can take.

Manitoba and Nova Scotia added their voices to criticism levelled by Ontario and B.C. that uncertainty in federal supply is slowing the local rollout. Dr. Strang said his province is taking a cautious approach to “protect Nova Scotians, and our vaccine program, from the uncertainty of a still unstable vaccine supply.”

He pointed out that delivery dates for the shots from Moderna changed twice in the past few weeks.

Unlike shipments from Pfizer, which arrive every week in predictable amounts, shipments of AstraZeneca doses are also unpredictable, and the vaccine is limited to certain age groups, Quebec Health Minister Christian Dubé said. “I’m hoping by Thursday or Friday we can get to 70,000 or 75,000 doses per day,” he said. “The 40,000 per day of Pfizer is easy. The rest is harder to predict.”

The province wants to give every Quebecker a first dose by the end of June, which will require a daily average of nearly 44,000 to reach the remaining 3.7 million people. “Over 44,000 people, I’m a happy man. Below that, I’m not,” Mr. Dubé said.

But even when supply is secured, thousands of appointments are unfilled. Over the four-day Easter weekend, 2,095 appointments were unclaimed in Toronto. In Montreal, it was 5,000, and in Hamilton, Ont., 662 appointments were unfilled on Monday alone.

In a bid to fill existing appointments and ramp up vaccinations as supply increases, Ontario is reducing the eligibility age to 60 province-wide starting on Wednesday, and to 50 or even younger in postal code areas where the risk is higher.

New data released on Tuesday by the Institute For Clinical Evaluative Sciences indicates that the areas with the highest COVID-19 burden are not the communities with the highest vaccination rates, suggesting more changes are needed to the vaccination campaign.

In the virus-battered areas of North Brampton and north-west Toronto, vaccination rates are almost half the provincial average despite having some of the highest rates of COVID-19. By contrast, some of the highest overall vaccination rates in the province are in Toronto’s wealthiest enclaves and in Kingston, the centre of a region that has logged relatively few infections and just one COVID-19 death.

Jeff Kwong, a senior scientist at the institute, said high vaccine coverage in some well-off neighbourhoods could reflect a large number of physicians and other health-care providers getting access to vaccines. But he said residents of those places are also more likely to be technologically savvy and capable of navigating the sign-up process, while residents of poorer neighbourhoods face barriers including language, and lack of access to the internet and transportation.

Dr. Kwong said the data make it clear that some parts of the province need more shots and more help.

Zain Chagla, an infectious diseases physician and associate professor at McMaster University, said he supports vaccinating people in high-risk regions, where many are essential workers, but urged the government to go further.

“If we’re going to use vaccines to dramatically shift transmission in our communities, we need to be going into high-risk neighbourhoods, high-risk workplaces, and vaccinating to a much younger age,” he said. “It probably won’t change our trajectory for months if we don’t get there.”

With a report from Kelly Grant

Article From: Globe and Mail