Mask mandates are likely to be gone this month, but a recent fundamental shift in masking has made N95s much more prominent, and unlikely to disappear. A look at how we got here.

Lori Huggins sells cloth masks on Etsy: “Calm down I’m wearing my muzzle,” one says. “I tested positive for refusing to live in fear,” reads another. Most customers who seek out her Make America Unmasked shop want to show how much they hate the masks they are forced to wear.

Andrew Mason also sells masks online, the made-in-Canada equivalent of the N95 respirator. The customers of “Canada Strong” follow the science and know that cloth and surgical masks aren’t good enough in the face of highly transmissible variants, he says, so they come looking for respirators that meet the 95 per cent particulate filtration efficiency guidelines of Health Canada.

In a pandemic where everything seems hopelessly political, the two starkly different shops have one thing in common. Both would be happy to give up their considerable mask sales.

“At the end of the day, I’d like COVID to go away and I’d like to not continue to operate this business,” Mason says. “That’d be wonderful.”

As an exhausted country emerges from the latest wave of this pandemic, provincial governments are loosening and eliminating restrictions. Ontario is planning to reconsider its rules on indoor masking this month. Even if the mandates end, the mask will not go away. Many people will still reach for an N95 respirator, a mask with a long history that loops in the development of decorative ribbons at American company 3M.

It has taken an entire pandemic to get this respirator on the faces you see at the grocery store, the subway and schools.

It’s been a long time coming.

At the outset of this long, grinding pandemic, public health officials told us to wear masks to protect each other, and most people turned to cloth or surgical masks because the good stuff — the N95 respirators — were in short supply, and health-care workers were the priority. Cloth masks were everywhere. They were a canvas for local artists, a small business success story, and they were endorsed by public health officials like Dr. Theresa Tam.

But in late 2021, with new variants more contagious than the last, many doctors and epidemiologists felt uneasy about the colourful scraps of fabric piling up on kitchen counters across the country. There was a growing acceptance that COVID was airborne, capable of lingering in the air in addition to spreading through droplets. As life moved indoors, the Public Health Agency of Canada updated its mask guidance for the public in November: “In general, while non-medical masks can help prevent the spread of COVID-19, medical masks and respirators provide better protection.” Then came Omicron.

In December, the head of the Ontario science table told people to ditch the cloth masks. As case numbers spiked, many turned to the respirator with a tight seal that filters out 95 per cent of particles. While Canada had no capacity at the outset of the pandemic, there were several companies churning out federally approved masks in the cup and flat-fold style.

Canada Strong was inundated with traffic, processing 8,000 orders a day for respirators in mid-December. Their suppliers raced to track down raw material to make more as global demand surged.

In late December, Tam, Canada’s top public health official, was photographed wearing a respirator when she got her booster shot. It was a fundamental shift.

The pandemic is not the first time the respirator mask has appeared in a paradigm-shifting moment of history. When the twin towers were attacked on 9/11, thousands were killed and the Manhattan air was thick with dangerous debris and dust.

Sara Little Turnbull was in her 80s then, teaching at Stanford. The industrial designer who grew up in Manhattan saved a newspaper with a photo at Ground Zero, where troops wore N95s. “I designed this mask. It put 3M in the medical business,” she wrote on a blue Post-it note.

When she died in 2015, the New York Times said she created an “anti pollution non woven face mask” for 3M. During the pandemic, dozens of stories have credited her as the inspiration for the mask.

But 3M says it is not a simple narrative.

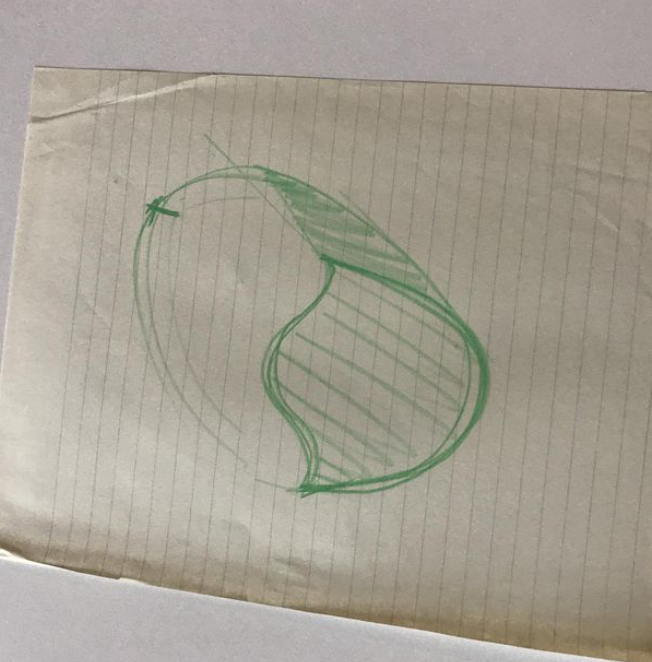

Everyone agrees on a few points: In 1938, 3M researcher Alvin W. Boese was on the hunt for a nonwoven fabric to use as a backing for the company’s electric tape. By experimenting with heat and pressure, he was able to bind fibres to create a synthetic fabric. It didn’t work as a tape backing, but he eventually came up with a successful gift ribbon. In 1958, Sara Little, as she was then known, was hired by 3M as a consultant.

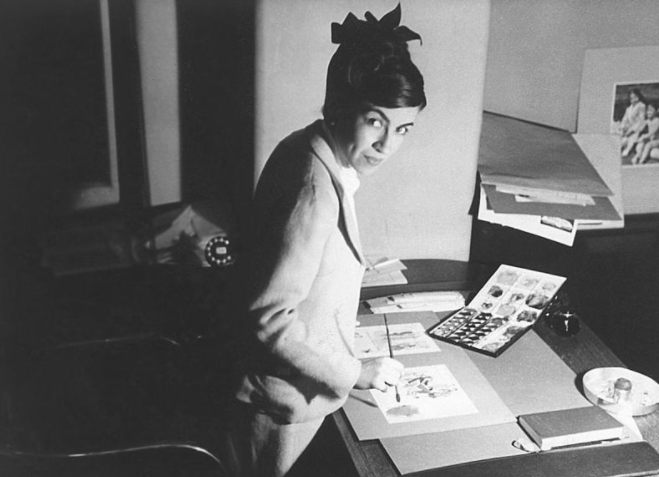

Little was a House Beautiful decor editor turned industrial designer who worked with corporations like Corning and General Mills. She understood science, manufacturing and business, and she drew inspiration from other cultures and creatures. She travelled the world on the corporate dime, usually wearing a fashionable hat and pearls. They called her a “pint-sized career girl” in the newspapers, and she was in demand.

Paula Rees, the president of the Sara Little Center for Design Institute, says that Little was “really taken” with the nonwoven fabric. She saw “unlimited potential” and made a presentation in June 1958, where she suggested around 100 product possibilities.

Little was assigned to work on a moulded bra cup, and later created a mask that had a similar shape, she says.

In its official history, 3M says it was scientist Patrick Carey who got the idea for cup-shaped nonwoven masks when he saw a display of curved Halloween masks at a local store. No year is given for that anecdote.

A 3M spokesperson says that notebooks from 1957 show the idea was in the works before Little arrived.

“I’m dying to see the proof,” Rees says. “If that was true why were they messing around with ribbon?”

She is not claiming Turnbull invented the mask, but that she was the inspiration for it.

“If you read their history books, there’s always this ‘someone’ mentioned, but it’s all these guys that are around this ‘someone’ who then did this or did that,” she says. “And I know that the someone was Sara.”

The path to the N95 is a long one. Even Pliny the Elder, who died in 79 A.D., has some skin in the game. In his book “Natural History,” he described people wearing “loose masks of bladder-skin” so as not to inhale the “pernicious” dust in workshops where people made red pigment. In the late 19th century, with the growing knowledge of germ theory, more surgeons began to wear masks of gauze.

In 1910, Dr. Wu Lien-teh was appointed by the Chinese government to investigate a deadly pneumonic plague. He created a surgical mask out of cotton and gauze and told people to wear it to protect themselves, leading many to call him a public health pioneer. That same year, the U.S. Bureau of Mines was created to help regulate an industry where many workers were dying. The bureau certified its first respirator in 1920. Many of these early industrial masks were bulky, and looked like gas masks.

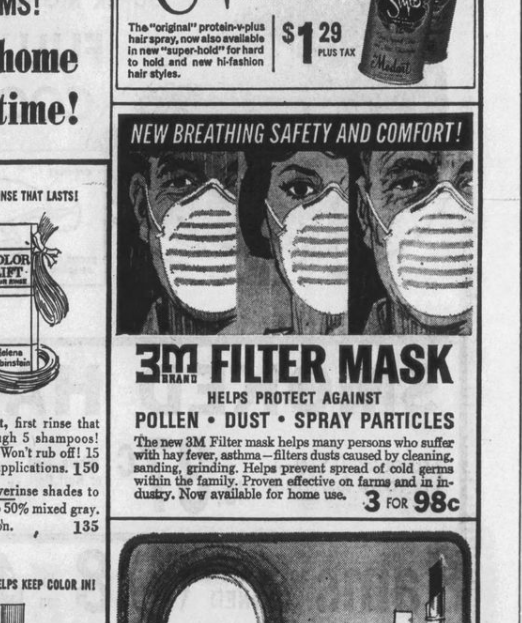

Greater concern about worker health and safety came into focus after the Second World War, says Nicole Vars McCullough, vice-president of 3M’s personal safety division.The company’s scientists filed a series of patents related to the nonwoven face mask, and in 1963 newspaper ads started appearing for their “filter mask.” In addition to industrial uses, the cup-shaped mask “helps prevent spread of cold germs within the family,” the ad stated.

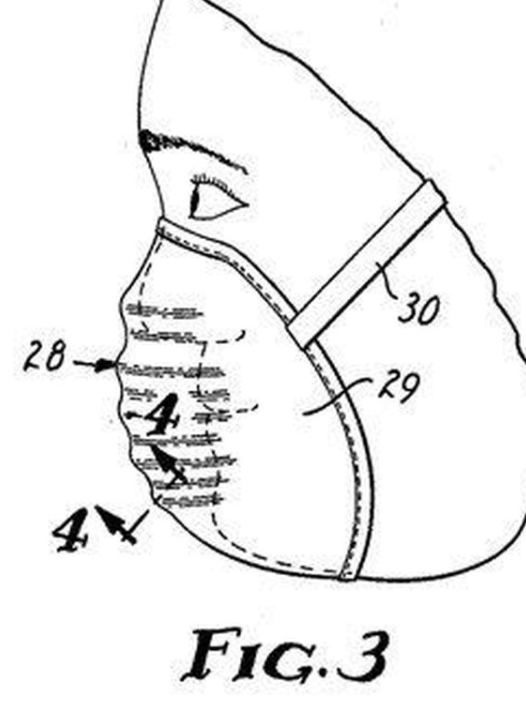

The nonwoven filter layer inside of respirators is most commonly made of “melt blown” polypropylene, explains Andrew Mason of Canada Strong Masks. It is created with giant machines that melt polymer pellets and then spray the liquid at high pressure in random orientation. Under a microscope, it would like a tangle of vines, says McCullough. Another crucial development was the addition of an electrostatic charge to the fabric. The charge helps the fibres attract particles, which means they don’t have to be as close together, which makes it easier to breathe through.

“It’s pretty special in how effective it is at filtering yet remaining breathable,” Mason says. “That’s the secret.”

Peter Tsai, a Taiwanese-American scientist at the University of Tennessee, patented an electric charge method for the fabric in 1995, and many articles call him the inventor of the N95. (The N95 is a standard, and not one specific mask.) 3M says it doesn’t use Tsai’s patents and notes that the company’s “electrostatic charging methodology” predates his work. 3M scientists filed a patent in 1978 that describes how they bombard their melted polymer with electrically charged particles as it is sprayed. In addition to proper fit and comfort, the charge is key to allowing respirators to filter out 95 per cent of airborne particles.

The N95 standard is applied to masks that meet criteria laid out by the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which was established in 1970. The N stands for “non-oil” (a marker of its industrial background — approved for use so long as no oil-based particulates are in the air).

Respirator masks have long been a staple of industry and began to replace surgical masks in hospitals in the 1990s to help reduce the spread of drug-resistant tuberculosis, says Barry Hunt, the president of the Canadian Association of PPE Manufacturers. (A fluid-resistant outer layer was added for medical settings, he says.) When the pandemic hit, N95 was a term on everyone’s lips, if not their faces, as governments rushed to secure supplies for health-care workers, and regular people were told to wear cloth.

Many countries have their own standards: China has the KN95. South Korea has the KF94. Until the pandemic, Canada didn’t have one: “We were lazy and just used the U.S. standards,” Hunt says.

About 10 companies across Canada make respirators that meet Health Canada guidelines. These masks are designated “95 PFE” (Particle filtration efficiency). During the pandemic the Canadian Standards Association developed a Canadian respirator standard. As of December, respirators that meet the requirements will be called CA-N95. The new standard will also have three categories that measure breathing resistance, whereas the U.S. standard only has one category.

As the Omicron wave recedes, and a new subvariant circulates, restrictions are easing. On Thursday, Ontario’s chief medical officer of health, Dr. Kieran Moore, said mask mandates could be gone by the end of March, as long as public health trends remain positive. University of Toronto epidemiologist Jeff Kwong says that it’s reasonable to relax restrictions as the situation improves, but masks should be the last thing to go, and he’d like to see cases and hospitalizations drop significantly. Ventilation indoors remains a challenge. Many people are vulnerable. Infants can’t get a vaccine, and they can’t mask.

“I think that’s a really compelling reason to keep the mask mandates,” he says. “It really helps to keep everyone safer.”

Several pediatric hospitals, including Sick Kids, have called for continued mandatory masking in schools for many of the same reasons.

Respirators are more expensive than cloth or surgical masks. In an ideal world, Kwong says, governments would provide high-quality masks and respirators, but logistics are complicated. (In Canada, some people have raised money on GoFundMe to buy masks for marginalized groups and families.) He says the more people wear masks, the less important the exact type is. “Respirators are more important when there are a lot of unmasked people around,” he writes in an email.

Kwong has been surprised by how masks became ensnared in politics; they are a low-cost intervention, effective when used properly, and seemingly not much of an imposition.

“I feel like there’s this culture here of nobody’s going to tell me what I’m going to do,” he says.

Lori Huggins’s Make America Unmasked shop is a good indication of that. Huggins is a Pennsylvania accountant who lost her job during the pandemic. Many of her customers see the mask as an attack on personal freedom and have concerns about effects on children. The masks, which include themes on tyranny and jokes about face diapers, reflect her political views, which have changed dramatically in the last two years.

Her shop is well reviewed: “if I have to wear ridiculous, useless masks, these are DEFINITELY the ones I wear! The messages are right on and hopefully thought provoking to those who are being brainwashed by FEAR!!” reads one.

Huggins says she doesn’t deny the many studies that show the effectiveness of respirators.

“I think that if everyone was given proper masks like N95 masks from the beginning, people would have seen the difference that they made, but to wear a piece of cloth and think that you are completely safe is kind of crazy,” she writes.

She has done very well selling masks, but wants a world where they aren’t needed. She has started to offer more T-shirts with right-wing political slogans anyway, in the hopes this will be over soon. One of her latest offerings is a Freedom Convoy shirt.

Article From: The Star

Author: Katie Daubs