So many people thought of the Saini family’s once-bustling Brampton, Ont. house as a second home. Now, it’s just another empty space.

Every summer Abhishek Saini tended to the plants in his garden. He’d grow zucchini and tomatoes, chili peppers and cilantro. He’d invite friends over for lunch on his family’s backyard patio. His father, Ramesh, would be puttering away in the garage, taking meticulous care of his cherished Lexus—the one Abhishek was not supposed to touch—cleaning it inside and out. Indoors, the aroma of curry spices wafted from the kitchen, where Abhishek’s mother, Bimla, a masterful cook, would spend hours preparing meals for the friends and family she loved to entertain.

In their living room, the three of them would chat with guests. Ramesh sometimes got lost in his favourite music, or would sit in front of the TV with his wife to enjoy classic Bollywood films. Their son would scare himself silly watching horror movies with his cousin, Heena Kumar, or his best friend, Ankit Arya.

Today, Abhishek’s garden is unkempt. The kitchen lacks the aromas of Bimla’s cooking. The living room is quiet. The master suite that Abhishek recently renovated for his bride-to-be, Aarjoo Branwal, with its marble-floored bathroom and his-and-hers sinks, is as immaculate as that of a luxury hotel room—and just as soulless.

So many people thought of this once-bustling house as a second home. For them, Bimla, 65, was a second mother, Ramesh, 67, was a second father, and Abhishek, 35—known to his friends as Abhi—was a brother or a son. Loved ones would drop by unannounced, knowing they would be offered something delicious to eat whether they were hungry or not. The house, in a residential neighbourhood of Brampton, Ont., about 42 km northwest of Toronto, is now just another empty space. In the span of five days this past spring, all three people who lived there died of COVID-19.

Canada has lost more than 27,000 people to the virus that upended all of our lives in 2020 and 2021. The world has lost an incomprehensible 4.7 million souls according to global statistics—and the true number is almost certainly higher. But in the daily barrage of caseload dashboards and vaccination bar graphs and lockdown updates, it is too easy to become numb to the pandemic’s immeasurable human toll.

During the isolation of the past 18 months, we could almost pretend that those we lost would still be there in the outside world when normal life resumed. Under pandemic restrictions, with no gatherings, few weddings and no travel, the loss felt less conspicuous. It was measured by the absence of text messages, the lack of phone or video calls. The only tangible proof was in the garden with the overripe tomatoes, the dusty television, the bedroom with the untouched things.

Ankit pulled up a chair next to the bed of his best friend, as he had done in so many hospital rooms before when Abhi was being treated for kidney disease. But it had never been like this. He sat with the sound of the machines that were keeping his buddy alive. When he spoke, he looked for a sign that Abhi was listening. He asked his forgiveness for anything he’d ever done to hurt him. He said, “I’m blessed to have you in my life.” Then he got ready to start the video call so others who loved Abhi could talk to him one last time.

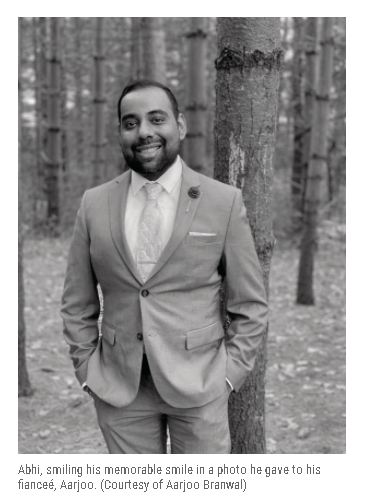

The Saini and Arya families met in the early 2000s. Ankit’s mother, Nutan, says mutual friends back in India put them in touch in the hopes of arranging a marriage between her eldest son, Anu, and the Sainis’ daughter, Menka. The two liked each other, marrying in 2005, and everyone else hit it off, too. The newlyweds’ teenaged brothers, Ankit and Abhi, became inseparable. “He’s beyond a best friend,” says Ankit, now 34 and the youngest of Nutan’s three sons. “He was a godlike figure in my life. I grew up with this guy. I discovered myself, who I am. He discovered himself, too, with me.”

They would have sleepovers, hang out at each other’s houses, work out at the gym and talk about everything. Abhi, who was a bit older than Ankit and soaked up knowledge like a sponge, helped his friend with his studies. And Ankit, who was a little more on the adventurous side, would push Abhi to come out of his shell, invite him to cottage parties and encourage him to talk to girls. They went everywhere together, including to Abhi’s hospital appointments.

Abhi, his sister and their parents had immigrated to Canada in 2000, when Abhi was 15. It was only a few months later, at the beginning of his Canadian high school career, that Abhi began suffering from severe kidney disease. He needed frequent hospital visits for tests and dialysis. “We were so new to the country,” Menka says. “We didn’t even know how to go downtown. But he managed everything. He became so self-dependent.”

Despite the frequent medical interruptions, including two kidney transplants, Abhi earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from York University and a graduate certificate in public administration from Humber College. Larry Till, who taught Abhi at Humber in 2011 and 2012, says he was a quiet, hard-working student whose devotion to his family and generosity of spirit were obvious to everyone. “When I talk to his classmates now, they express something close to love for him, which is very unusual. They just all talk about how gentle he was, and how thoughtful, and how open and giving.”

In 2012, Till put Abhi in touch with Taylor Gunn, the president of CIVIX, a Toronto-based charity that runs civics and student-vote programs for young Canadians. Even though Abhi could go in only part-time due to his health issues, Gunn decided to give him a chance, hiring him as an intern. Abhi ended up working at the non-profit for eight years, handling finances and administrative matters and sometimes writing for its blog. He’d go above and beyond, having his boss over for dinner on the weekend to walk him through computer troubles or sort through travel receipts. Though they bonded over their health issues—Gunn has Type 1 diabetes—Abhi never complained or let his condition interfere with his work. “This is the strongest guy I know,” Gunn says.

Every day before Abhi came in, he would stop at a Tim Hortons in downtown Toronto, getting himself a coffee and a bagel and buying a 20-pack of Timbits for everyone else. At the office, he would chat with Dan Allan, the director of content, about movies and TV shows. Abhi thought all of the Marvel movies were worthwhile, but he also liked Batman v Superman. He recommended that Allan check out Black Mirror and Narcos on Netflix.

Catherine McDonald, a colleague of Abhi’s from 2016 to 2019, wasn’t one for TV shows, but she knew she could always get Abhi talking if she asked about his loved ones. “Not everybody talks that highly about their parents and their sister,” she says. “For him, they were the centre of his universe. It was his family first, over and beyond anything else.”

When Abhi’s sister had a baby in December 2019, his former colleagues say, it was all he could talk about. Lindsay Mazzucco, the charity’s chief operating officer and Gunn’s spouse, says: “The happiest I ever saw him was when he became an uncle.”

On the video call, Heena told her cousin that she missed him, and that she was praying for a miracle. “But,” she recalls, “at the same time I told him, ‘I want you to be comfortable, be at peace, no pain.’ I was at a loss for words. What do you say to somebody you’re so close to in those last couple of minutes?”

Abhi’s parents, Bimla and Ramesh, were almost never apart. Back in New Delhi, both worked as income tax officers at India’s equivalent of the Canada Revenue Agency. They’d go to work together in the morning and come home together at the end of the day. Those who knew them say they were hard-working, gentle, kind people who never raised their voices with their children. “I don’t remember my father getting angry with anybody,” says Menka, now 40. Bimla was the stricter parent, especially when it came to her children’s studies. But if she ever said no to something, the kids would appeal to their father, who’d usually say it was okay, and Bimla would relent.

Growing up in Delhi, Abhi was a quiet kid and preferred solitary activities like drawing and painting to running around with other children, Menka recalls. The family was not strictly observant of their Hindu faith, yet her brother was a deeply spiritual person from a young age and remained so as an adult. At the same time, he loved pop culture. When the Sainis arrived in Canada, they were reunited with their aunt and uncle and their daughter, Heena. She and Abhi would watch horror movies at his house—the “really creepy ones,” she says, like the Annabelle and Insidious series. She remembers being intrigued by Abhi and his artistic skills right off the bat; he could make something interesting out of an old tissue box.

Soon after their arrival in Canada, Ramesh and Bimla both found jobs with a caterer that supplied food to airlines. As was the case in Delhi, for many years they commuted together every day. Bimla began to suffer from arthritis in her knee and left the job around 2010, her daughter recalls. Ramesh worked there until about 2018.

Over the years, as Abhi and Ankit bonded, their mothers grew close, too. Nutan says Bimla loved her so much she’d sometimes lift her off the ground when they hugged. They were less like in-laws and more like sisters.

Ramesh, Bimla and Abhi were devoted to Menka’s infant daughter, Aarna, now almost two years old. Uncle Abhi would spoil her with toys, clothes and books, and he was already starting to research which schools she should attend. After pandemic restrictions began, her grandmother Bimla would insist on FaceTiming with the baby two or three times a day. They couldn’t wait to be together again.

“I told him, ‘I’m not going to say goodbye to you. Because I know you will come back. I’m going to wait for you,’ ” says Abhi’s fiancée, Aarjoo Branwal. In another life, she is sure Abhi will make an appearance. He might be a friend, or a lover or a son. But he’ll be back. “I knew he was in pain. I was telling him, ‘I don’t want you to suffer, so you can go, but I am waiting for you.’ And I saw tears coming out of his eyes.”

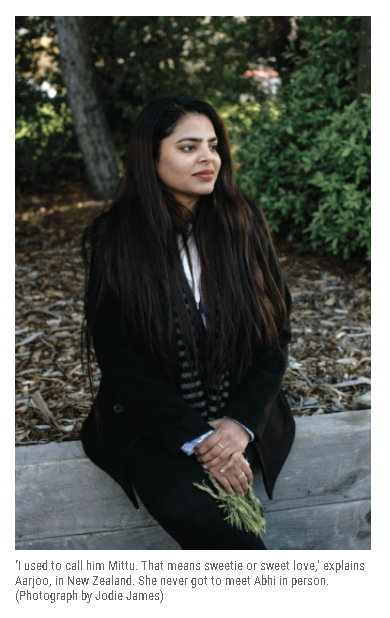

In January 2020, Nutan Arya was visiting family in New Zealand. Their tour of the South Island brought them to a hotel near Queenstown whose manager, Aarjoo Branwal, had an infectious personality. “When I talked to her, she was always laughing, laughing, laughing,” says Nutan. “First she laughs, and then she talks. I really liked that girl. I said, ‘I want to take you to my home in Canada . . . I will look for a boy for you.’ ” Aarjoo figured her new acquaintance was joking but responded, “Why not?” With the blessing of the Branwal and Saini families, Nutan put the young woman in touch with Abhi.

The two started texting in January 2020. Despite the distance and time difference, they quickly became close, messaging back and forth during the eight or nine hours a day when they were both awake. “The family arranged our marriage, but as soon as I was getting to know Abhi, I fell in love with him,” says Aarjoo, 26. “It was not arranged anymore.”

Abhi was concerned whether she understood what his health issues could mean for their relationship, and if she would be okay if something happened to him, she continues. She would reassure him, asserting, “No, nothing will happen to you—because love can change everything.”

Less than three months after their first conversation, they got engaged. Despite the lockdowns underway in both countries, Abhi managed to have a ring delivered by courier. The pandemic delayed their wedding plans indefinitely, but their relationship flourished online and by mail—she’d send him handwritten notes planted with red lipstick kisses. They would eat together on video chat (her breakfast and his dinner, or vice versa) and send each other food from Uber Eats. He had a cake delivered on her birthday in July 2020. “Although we both sit at great distances, your warmth and love is felt every single day like a morning sun,” he wrote to her in a birthday letter. “I love everything about you. I do not think I will stop feeling butterflies every time I see you. I promise to never leave you.” Aarjoo’s friends thought this was all pretty cheesy, she says. “But this is not cheesy for me. For me, we were creating lots and lots of memories together.”

Around September of last year, Abhi took on a new job working with Ankit and his brothers at their Brampton real estate firm. He was nervous to leave CIVIX, but his boss encouraged him to take the next step in his career. Gunn remembers telling him, “Abhi, all this stuff is coming together right now. You’ve got to jump on this, man.” They had a goodbye lunch on the Sainis’ patio.

Abhi took to his new job like a fish to water, as Ankit describes it. And he seemed genuinely happy. At the real estate office, he would gush about his fiancée. One of his new colleagues connected with Aarjoo on Instagram and sent her a video in which Abhi is leaning over a cubicle wall in a grey sweater. “She’s a wind that can’t be tamed, you know,” he says, leaning in, hands folded. “She’s wild, and that’s what I love about her.” He goes on for about 30 seconds before noticing he’s being filmed, then gives a bashful smile.

Abhi isn’t wearing a mask in that video, though family and friends say he was keenly aware of how vulnerable he was to COVID-19. Ankit remembers getting mad at him sometimes. “I kept yelling at him, ‘Wear your mask! Take extra precautions!’ ” he says. “Being locked down for so long, you kind of let your guard down once in a while.”

Around the beginning of February, a client came into the office with a bit of a cough.

It turned out the client had the alpha variant of the disease. His visit to the office that day caused an outbreak in the Arya and Saini families. Ankit was hospitalized for five days, his mother for one. His wife and his brother got sick. And to everyone’s horror, so did Abhi.

It was such a whirlwind of bad news that the families have trouble pinpointing what happened on which date. But the dominoes fell something like this: around mid-February, Abhi went to the hospital with a fever, where he tested positive for COVID-19. By the end of February, he had to be put on a ventilator. Two days later, his mother suffered a minor stroke and was brought to the ER. Her prognosis was encouraging, but then she tested positive for COVID-19. A few days after that, Ramesh went to the hospital with worsening symptoms and tested positive, too. With the Brampton Civic Hospital’s ICU over capacity, Abhi was moved to Hamilton and Ramesh to St. Catharines, Ont. “It felt like the sand was slipping through our fingers,” says his cousin Heena. “We had no control over everything.” Soon all three of them were on ventilators.

Ramesh used to tell his wife that he wouldn’t be able to live if anything ever happened to her, says Aarjoo. Bimla would get embarrassed and chide him, “We are old, we are in our 60s, and you’re still saying these things?”

The family believes that on some level what happened was meant to be. Bimla succumbed to the virus first, dying at around 3:30 a.m. on March 9. Though Ramesh had been in decent shape, his oxygen levels plummeted over the course of that day and he died at 10:30 p.m. Even the doctor suggested he may have sensed his wife’s passing, says Menka.

Menka wasn’t sure if Abhi could hear her. But she finally conveyed the news they had all been holding back for days. “I did tell him, ‘You have to go,’ ” she says. “ ‘Mom and Dad are waiting for you. So don’t worry. You are going with them.’ His eyes were closed but tears were coming out, so he was listening. I cannot forget that face.”

Ankit got the okay to visit Abhi in Hamilton over the days that followed. On March 14, a doctor told him Abhi was experiencing multiple organ failure and there wasn’t much time left. It would be best to turn off the ventilator soon. That’s when everyone closest to Abhi said their goodbyes through Ankit’s phone.

Months later, those whom Bimla, Ramesh and Abhi left behind are still grappling with how to process the loss. After watching his best friend die in that hospital room, Ankit has resolved to “live a better life.” Menka feels her brother’s absence most when she craves his advice, or when she notices something nice—like how beautiful the weather is—and has an impulse to text him about it. The fact that her daughter won’t get to know her uncle and grandparents weighs heavily. “My happiness is sharing my happiness with them,” she says. “I’m not the person I was, and they’re gone. They left me with so much anxiety, so much fear, so much sadness. I don’t know when I’m going to come out of it.”

Aarjoo, who lost her father several years ago and has been living in New Zealand alone, is coming to grips with all the lost potential of a new family and a new life. She is dealing with the fact that she never got to meet the person she fell in love with in person. She says she still finds herself texting him goodnight in the evening. “When I go to sleep, it’s the hardest time for me, alone, gathering my thoughts,” she says. “And then I talk with Abhi. It makes me feel crazy, but I close my eyes and imagine I am talking to him. Every night, I pray to him, ‘Just guide me toward what you wish for me to do.’ ”

As the loss sank in for Ankit’s mother, Nutan found herself troubled by the knowledge that Abhi and his parents died not long before they would have been eligible to receive COVID-19 vaccines, which at the time were coming in to Canada at a slow trickle. The tragedy was compounded, too, by the knowledge of how viciously COVID-19 tore through India soon after, where more members of her family contracted the virus. “All the time we were talking to God: ‘It’s not fair that you took all three. It’s not fair,’ ” she says. She still sees a daughter in Aarjoo and hopes to welcome her to Canada one day.

For her part, Heena has been reflecting on the house. Not so much the structure itself, which, as Ankit puts it, has become an “empty shell.” More so what that house represented: a second loving home; a safe, happy place. “To say that that’s not there anymore?” she says. “Right now because of the pandemic, the lockdown restrictions, it’s not hitting me as hard. But I can already see that, once these restrictions open, I’m going to really feel that sense of: ‘Where do I go now?’ ”

Article From: Maclean’s

Author: Marie-Danielle Smith