When more transmissible variants of the virus that causes COVID-19 first began arriving in Canada late last year, they accelerated the rate of infection. Now, case data accumulated in Ontario over several months show that the disease has become substantially more dangerous as well.

That assessment, published on Tuesday in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, offers the most in-depth look to date at the changing risk posed by COVID-19 in Canada. And it comes with important implications for those who remain unvaccinated: Namely, the experience of an individual who caught COVID-19 last year and was lucky enough to fight off the virus with little apparent effect is not a reliable guide to how the disease may affect someone in similar health today.

“The risks have really markedly changed,” said David Fisman, a professor of epidemiology who co-authored the study with mathematical modeller Ashleigh Tuite. Both are based at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

The large-scale study was based on the outcomes of more than 212,000 cases in Ontario between February and June of this year. Dr. Fisman said the sheer volume of data available allowed him and Dr. Tuite to control for a wide range of variables – including age, sex, vaccination status, and unrelated health conditions that might make a case of COVID-19 more severe in some people – to show that the virus has indeed become more virulent.

The finding is consistent with those of other studies. They suggest that the versions of the virus that the World Health Organization identified as “variants of concern” are generating many more serious cases of COVID-19 – and not just because they spread more easily.

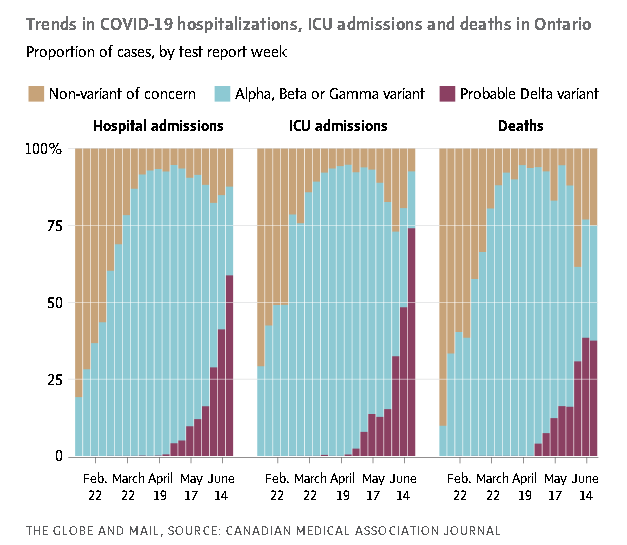

Overall, the Ontario study found that three variants of the virus known as Alpha, Beta and Gamma were 52 per cent more likely to put people in hospital, 89 per cent more likely to lead to cases in intensive care, and 51 per cent more likely to cause death than the version of the novel coronavirus circulating in 2020. All three share a common mutation linked to increased transmission. Earlier this year, the Alpha variant was the main driver of the third wave of the pandemic in Canada.

After the Delta variant began to emerge in late spring, the statistics became even more grim. Delta now accounts for the vast majority of Canadian cases. Compared to someone who caught COVID-19 in Canada a year ago, an individual who is infected with the Delta variant today is 108 per cent more likely to end up in hospital, 235 per cent more likely to be placed in ICU, and 133 per cent more likely to die.

While the study does not include what happened since Delta powered a fourth wave of the pandemic in Canada, it helps explain some of the characteristic features of that wave. For example, even though more than two-thirds of the Ontario population was fully vaccinated by early September, hospital and ICU cases because of COVID-19 were about three to six times higher than they were at the same time last year.

“The virus has become smarter and more dangerous, which means we have to be smarter too,” Kirsten Patrick, the journal’s interim editor-in-chief, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In a follow-up to their study that was posted online last week and is awaiting peer review, Dr. Fisman and Dr. Tuite looked more closely at disease outcomes across different age groups. They found that the relative risk of ending up in hospital with COVID-19 is now increasing with diminishing age. In other words, while people of all ages face a higher threat because of the variants, those who are younger and more able to dodge severe disease are seeing that advantage diminish. The researchers caution that low numbers of ICU stays and deaths among children with COVID-19 mean uncertainty is higher about estimating those risk levels among the youngest.

Dr. Fisman said one takeaway of the combined studies is that vaccination should not be regarded as simply an altruistic choice that primarily keeps severe disease from spreading to older and more vulnerable populations.

“It’s very much about direct protection,” he said.

Alyson Kelvin, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization, said the Ontario study is important because it captures a hard-to-measure aspect of the virus at a time when the pandemic was in transition from its initial phase with no recognized variants of concern but also no approved vaccines to one where vaccines and variants are interacting and having a profound effect on disease dynamics.

“I think it really drives home the importance of the variants and of getting people vaccinated to prevent new variants from emerging,” said Dr. Kelvin, who was not involved in the study.

On Monday, the Saskatchewan facility said Dr. Kelvin has received federal funding to launch a new project that will look at the risk that variants pose to vaccine efficacy in vulnerable populations, including the elderly and those who are HIV-positive. As part of the international year-long project, Dr. Kelvin will analyze antibodies collected from vaccinated participants in Canada, Italy and Rwanda.

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: IVAN SEMENIUK