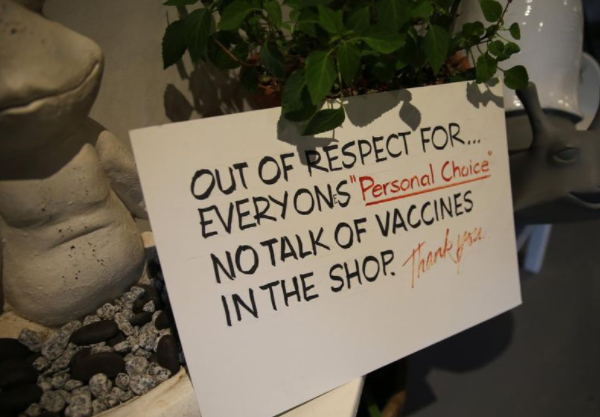

DUNNVILLE, Ont.—At Stefanie’s Family Hair Care in downtown Dunnville, beside a statue of a blissed-out frog, a sign greets customers: “Out of respect for everyone’s ‘Personal Choice’ no talk of vaccines in the shop.”

Owner Stefanie Price was tired of the arguments. Clients would come in for highlights only to find themselves in a heated battle with another customer over masks or vaccines. She longed for simpler times, when people complained about their husbands or the weather. “Anything but that,” she says.

She won’t say whether she is vaccinated. Customers haven’t asked, and she wants to remain neutral. Her salon is meant to be a place to relax and talk about life — just not the one conversation that’s dominating and dividing the town.

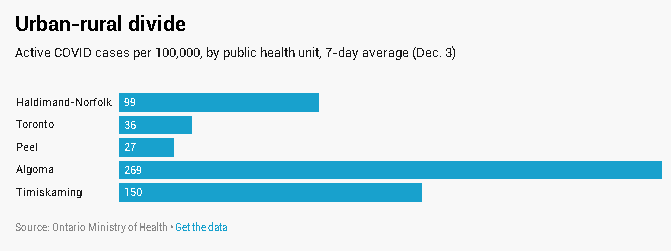

In the first waves of the pandemic, densely populated places like Toronto and Peel were hit hard while many small towns were relatively sheltered from the virus. But this fall, the trouble is increasingly found in wide-open spaces, as more rural communities struggle with higher case counts. In late October, one in 10 people in the Dunnville area who had a COVID test was positive for the virus as outbreaks hit the local hardware store, hospital and a school. Northern Ontario is also seeing concerning numbers: The most recent data shows Algoma and Timiskaming at the top of the charts for positive tests, along with the Haldimand-Norfolk health unit in southwestern Ontario, which includes Dunnville.

Some places struggling with COVID-19 have not embraced vaccination as enthusiastically as many bigger cities have. In Aylmer, a southwestern town with notorious vaccine resistance, the virus continues to fester, overwhelming the regional hospital and disrupting schools. At the end of November, the public health unit brought back capacity limits for eight towns in a bid to stop the spread.

Todd Coleman, an assistant professor of health sciences at Laurier University, says that while you’d need a detailed breakdown of vaccine status to determine whether the lower vaccination rates are driving virus spread, there is a “rural-urban divide” with vaccines.

Dunnville has the lowest vaccine uptake in the Haldimand-Norfolk Health Unit, a region that is itself below the provincial average. Dr. Matt Strauss, acting medical officer of health for Haldimand-Norfolk, says that lower uptake is a factor in spread, but not the whole story. He explains that communities with higher vaccination rates likely have higher adherence to public health measures. There is also the risk of waning immunity for vaccinated people — why booster shots are so important, he says.

While the majority of people in Dunnville are vaccinated, the holdouts are a skeptical group. An independent streak runs through this part of the province, where the habit of questioning authority tends to begin with the authority figures themselves. Back in June, county mayors Kristal Chopp and Ken Hewitt had protest haircuts when their region was left behind in provincial reopening. In October, Conservative MP Leslyn Lewis (Haldimand-Norfolk) said Canadian children were being used as “shields for adults” with vaccines.

Before his appointment, Strauss made the kind of posts you don’t tend to see from a prospective public health leader. When Florida reopened without restrictions, he asked how he could apply for refugee status. When Premier Jason Kenney said that it was “time for media to stop promoting fear” in July, before Alberta’s “best summer ever” ended in a state of emergency, Strauss retweeted him. Throughout the pandemic, the ICU doctor has questioned the efficacy of lockdowns.

Kristal Chopp, the mayor of Norfolk, who is also the chair of the board of health, brushed aside his “colourful Twitter feed” in the Port Dover Maple Leaf after his hiring caused major controversy: “First, let me state that Dr. Strauss doesn’t wear a tin foil hat, attend QAnon meetings or espouse conspiracy theories,” she wrote. “Let me make this Kristal Clear, Dr. Strauss believes in vaccinations, which the last time I checked is the strongest public health measure we have available in our tool box.”

“The status quo hasn’t worked but maybe, just maybe, someone like Dr. Strauss can provide a unique perspective and better connect with those that remain skeptical that vaccinations are indeed our way out of the pandemic.”

On the drive into Dunnville, visitors are greeted by a gigantic catfish. Muddy is a nod to the fish that swim in the nearby Grand River and a source of pride as the biggest mudcat statue in the world. Earlier in the pandemic, the fish was protected by a blue mask, but on a recent autumn day, the flat-headed fellow was gaping at cars as they drove into town from the surrounding farmland. Located just north of Lake Erie, this used to be a factory town, but now it’s a bedroom community for Hamilton and Niagara.

The Haldimand War Memorial Hospital is a major employer. Built to honour the sacrifices of First World War soldiers, the downtown hospital is a beloved institution. For the last four years, the local Tim Hortons has sold the most Smile cookies in Canada, with proceeds going to the hospital foundation. In 2021, that worked out to eight cookies for each of Dunnville’s 6,000or so residents.

The hospital nearly closed during the Mike Harris era, and people still talk about the rally to save it. When the bureaucrats showed up for a meeting at the hospital, farmers sat atop tractors and combines. People marched through the streets, defiantly waving protest signs: “Kill our hospital and you kill our town.”

Back then, it was clear whose side everybody was on. That’s not the case anymore.

At the hospital, early support of health-care “heroes” gave way to something more complicated. Anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers made trouble, denying the science, arguing with staff, sometimes becoming violent, says the hospital’s president and CEO, Sharon Moore. Some employees retired early or quit.

In the early days of the pandemic, Dunnville felt far from the fear that gripped cities like Toronto. But the virus eventually arrived. Haldimand-Norfolk has the second-largest population of migrant workers per capita in Ontario. The people so crucial to the province’s food supply live in bunkhouses, which made them especially vulnerable to COVID outbreaks. Some restrictions put in place by the health unit were met with protest and legal action by the farming community.

Jacob Shelley, an associate professor at Western University’s faculty of law and school of health studies, is originally from nearby Simcoe. This part of the province is often overlooked, he says.

“It’s easy to to not pay attention, but there is a pretty dominant perspective of some things, including farming,” he says.

With vaccination rates lagging in the region in September, the hospital implored locals to get vaccinated. Dunnville has the lowest uptake in the health unit, and stats show the numbers haven’t moved much, even after the outbreaks this fall. Currently, 76.6 per cent of people over 12 in the Dunnville postal code are fully vaccinated. In Haldimand-Norfolk, 81.8 per cent of people are fully vaccinated. Both numbers are below Ontario’s vaccination rate of 87.2 per cent. Since peaking in late October, the rate of positive COVID tests is now back in line with the provincial average.

At the Tim Hortons, locals rush inside, their winter jackets zipped tight against the north wind. It’s a friendly crowd, and everyone who chats is vaccinated, except for one maskless man ordering a breakfast sandwich, but he is from Welland. “There’s nothing we can do about it,” says a fully vaccinated Joyce Marr. “There’s no sense fighting with them.”

A few streets away, at the public health office, seniors show up every 10 minutes or so for their booster. This morning, the news is bleak. A new variant called Omicron has put the world on edge.

Logan Ritchie, 19, has also come for his third shot. “I’m on the town’s Facebook group, and it is a war zone,” he says. In one recent post about booster shots, one man calls the vaccine an “experiment on the homosapien race.” Another says: “It is 100% fear-mongering to get everyone divided and compliant. I can’t believe people can be so blind.”

Not everyone is peddling conspiracy theories. Some are concerned about side effects, some distrust the government. In a Facebook message, one local tells the Star that she doesn’t fully believe in COVID: “I believe it exists but is not what they (the government) make it to be.” Vaccine resistance and misinformation are problems in cities, too. But with fewer health-care professionals in rural areas, social media and word-of-mouth can fill the vacuum, says Todd Coleman. “Fear-based messaging … goes a lot faster and works its way through a community.”

“We’re fighting against a lot of misinformation, and a lot of rhetoric, for lack of a better word, on social media,” says Sarah Page, the chief of the region’s paramedic service, and the vaccine lead until recently. But they’ve made gains. At the bottom of the provincial vaccine rankings this summer, the health unit is now in the “middle of the pack.”

Bernie Corbett, the Haldimand County councillor who has represented Dunnville for many years says he received a letter from a disappointed supporter when he shared information about vaccines.

“I’m sorry,” Corbett says in an interview. “You may have supported me, but this is my belief.”

Dunnville has a strong religious population, he says, and some have objections. “Their comment is ‘the Lord will look after me.’ I do not choose to marginalize these comments,” he writes in a followup message. “I respect they have their beliefs.”

There are more than a dozen churches in Dunnville, and four are reformed churches. One pastor said that while many members of his congregation are vaccinated, others are not. “We try to walk a narrow path … not inflaming one side versus the other,” he says, declining to go on record because it’s so divisive. “You know, we’re all tired.”

While rural communities are seeing higher case numbers now, they’ve had fewer cases per capita than urban centres over the entire pandemic, Strauss says. If you are going to have outbreaks, he says, it is better to have them when the majority of people are vaccinated.

Strauss says his main priority is “getting folks vaccinated and addressing vaccine hesitancy.” He invites people to call him with their questions and concerns. Most who do aren’t misinformed, he says, but concerned that the facts don’t apply to their situation or values. There is also unease with vaccine mandates.

“I had one gentleman flatly tell me “I am not getting it so long as they are forcing me to get it,” Strauss writes in an email.

Jacob Shelley says it is not the job of a medical officer of health to have one-on-one talks. People should talk to their doctors. It’s a “highly problematic approach,” he says, when there is so much that has to be done in that role, “like managing outbreaks.” Shelley is also concerned about what Strauss might be saying, “given his track record.”

Strauss says he spends 20 minutes a day talking to hesitant people, and is “grateful for the opportunity to better understand” where they are coming from. He believes his criticisms of certain restrictions have given him “additional credibility” in some quarters.

“I frankly can’t think of a better use of my time than having one-on-one conversations with people for whom vaccination could make a tremendous health difference,” he says.

Strauss does not have a public health degree, which is not required of acting medical officers of health. He says that a master’s degree isn’t the only way to learn. He cites his ICU work and the public health education in his medical training.

Some of his communication choices are notable. In one dispatch reminding people to stay vigilant against COVID, he did not include the suggestion to mask.

Strauss says evidence for masks is “just a bit murkier” than that of vaccines. (The Public Health Agency of Canada has called masks essential. Dr. Theresa Tam has urged Canadians to continue to wear masks to prevent airborne transmission of the virus, as evidence shows particles can linger, “much like second-hand smoke.”)

“I don’t doubt that they are beneficial in some situations,” he writes in an email, adding that he wants to use his “credibility capital” where it matters most.

“ ‘Vaccines can save your life’ is a very simple story,” he says. “I would rather stomp my foot and insist on vaccines prevent death.”

In November, the provincial Liberals called for his removal for “undermining vaccination efforts,” when Strauss told local media that parents should consider their own values, along with the risks and benefits, and talk to their doctors when it came to vaccinating children: “I cannot make a blanket recommendation for children that I have never met,” he said.

Strauss explained that Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization advises the vaccine “may be offered to children,” as opposed to the stronger language it uses for adults, who “should” get the shot.

“I CAN ‘make a blanket recommendation for children that I have never met’ — get vaccinated for your health, your family’s health and for the health of the public you are part of,” Toronto ER doctor Raghu Venugopal tweeted.

Strauss clarified on Twitter that he was happy that a safe and effective vaccine was available for children, which “could make a humongous difference in local transmission dynamics.” He included a screenshot of the NACI guidelines.

This time, it was a different sort of follower who balked.

“What a disappointment to see. Thought you were going to be a voice of reason and change but I guess they got to you.”

At the hair salon where she has trimmed Dunnville heads for 20 years, Stefanie Price eats some A&W with her parents, who have businesses in the same building. Her father made the sign. People are relieved to see it, she says, even if it doesn’t always work. The pandemic has made people meaner, she says.

“In the beginning, everybody was like, ‘Let’s help each other.’ Now it’s like people don’t even talk to each other.”

Price has always loved the way people in Dunnville rally: If your house burns down, if you’re in need, this community always comes together.

“I’m hoping this doesn’t wreck that.”

Article From: The Star

Author: Katie Daubs