This post is also available in: 简体中文 繁體中文

About 20 clinics across Canada are specifically helping the so-called long haulers

“I haven’t picked this up in 6 months.” Derek Christie slowly strums a few chords on his guitar.

The 60-year-old musician from Richmond Hill, Ont., nearly died of COVID-19 twice over the last eight months. But survival was only the beginning of a long road back.

Christie is one of the more than 170,000 long-COVID patients across Canada. Like the others, he faced a mystifying array of lingering after-effects, from tinnitus to intense pain throughout parts of his body.

“The cough, the fatigue, the aches and pains, hair loss, occasional insomnia, brain fog, like I’m having now,” he said.

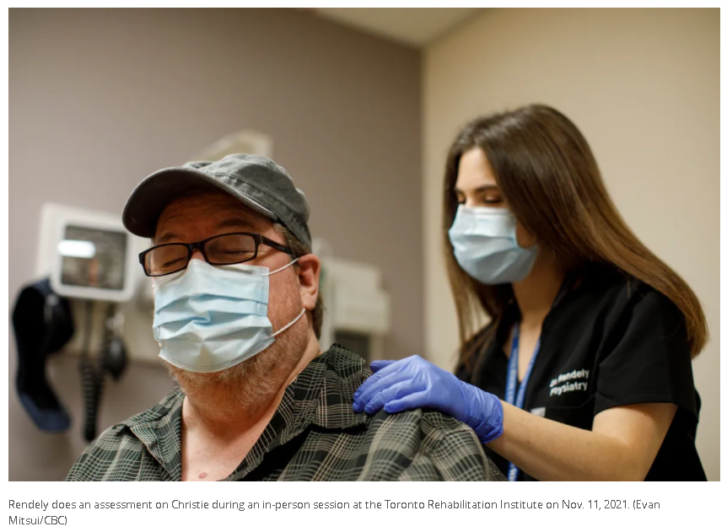

Christie is getting help. He’s an outpatient at a clinic offered by the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, where he’s seen — both in person and virtually — by a team of experts.

It is one of approximately 20 such clinics across the country that specifically help patients grappling with a much longer than expected recovery from COVID-19.

At the moment, there’s no known cure for long COVID, so doctors are creating their own treatment playbook for those affected by lingering symptoms of the disease.

“We’re really able to take evidence-based information that’s been studied in other populations, with similar symptoms but from a different virus, a different pathology — stroke, MS, spinal cord injury — and take that research and bring it to our COVID rehab patients,” said Dr. Alexandra Rendely, a physiatrist who has been working with Christie.

Long-COVID patients — sometimes called long haulers — are defined as those who have at least one unexplained symptom lasting longer than 12 weeks.

According to studies, long COVID is associated with more than 200 symptoms across 10 organ systems, including the brain, heart, lungs and blood vessels. A large Canadian survey released in June found the top reported long-COVID symptoms included fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog and muscle and joint pain.

Learning on the fly

It’s been a learning experience for Rendely and her team of physio and occupational therapists. They are trying to figure things out as they go, treating patients who can be fine one day and terrible the next.

Even if Rendely and the others can’t find anything structurally wrong with their patients, it doesn’t mean the health concerns are less valid. “I think as physicians we should believe our patients with the symptoms that they’re experiencing,” she said.

Doctors working with long-COVID patients are already employing some additional investigational tools, such as the use of a special MRI, which allows doctors to dilate the brain’s capillaries and see how slow they respond to stimuli. It may help explain brain fog in some patients.

“We have already learned a few things,” said Dr. Angela Cheung, a senior scientist-clinician at the University Health Network in Toronto, which includes the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute. She is also co-lead investigator for the Canadian COVID-19 Prospective Cohort Study (CANCOV), which is looking at the one-year outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

Resting and pacing yourself, for example, helps with recovery. Deep breathing can also help patients get rid of shortness of breath. Steroid puffers can be used for wheezing and cough, as well as steroid nasal sprays for runny noses and sinus congestion.

But doctors still aren’t sure why COVID-19 lingers in some people — and not in others.

Genetics may play a role, said Cheung. Other theories speculate that long COVID is a powerful immune reaction caused by the virus. And there’s the idea that perhaps the virus causes damage to the nervous system and other parts of the body, which is difficult to discern.

“Is it the residual viral particles that are not being cleared that’s causing sort of a problem in our system? Is it an inflammatory response? Is it the … endothelial function? That’s the lining of the blood vessels,” said Cheung.

At the long-haul COVID rehab clinic at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Katy McLean has also been working through debilitating after-effects from her bout of the disease in September 2020.

Her recovery has ebbed and flowed, but last February, it got really bad. Shingles, arthritis, numbness in the legs, headaches, vascular dysfunction and a condition known as POTS, or Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, which causes, among other things, sweating and wildly fluctuating heart rates.

“I can’t stand for more than a few minutes. I can’t walk more than a few metres. And I use a lot of mobility aids now,” said McLean, 42, who was a healthy, active woman with a full-time job in an urban planning office when she got COVID-19.

The team of doctors and therapists at St. Paul’s is part of B.C’s Post-COVID-19 Interdisciplinary Clinical Care Network, which oversees more than 2,600 patients — a number that is growing.

Standardization to detect patterns

According to Dr. Adeera Levin, the network’s medical lead, they’re also trying to develop strategies for an illness they had never seen before.

“Although we understand a little bit of the biology of the infection, we’re not so sure, because we haven’t had 15 years of time to understand what are the true short, medium and long-term consequences of having had infection with this virus,” she said.

Patients are now required to answer a standardized questionnaire every three months, and regularly scheduled blood tests can help the medical team detect patterns in the cases they see.

All of this is a work in progress, said Levin, which will hopefully give doctors clues in regularly updated data. At the same time, she said, “we are trying to learn and create care pathways for this group of patients.”

They are being helped along by the more than 600 global studies registered to examine long-COVID, though they haven’t yet produced any results.

Cheung and her partners at CANCOV are themselves hoping to begin a controlled trial in 2022. Known as RECLAIM — which stands for Recovering from COVID-19 Lingering Symptoms Adaptive Integrative Medicine Trial — they’ll be recruiting 1,000 patients from across Canada to study the underlying causes of long-COVID and to look at promising therapies.

One such possibility is coming from the University of Oxford, where researchers have started a Phase 2 clinical trial on whether the drug, AXA1125, developed by U.S.-based Axcella Therapeutics, can treat the fatigue and muscle weakness many long haulers experience.

Another American biotherapeutics company, PureTech, announced a global Phase 2 trial last year for its prospect, LYT-100, to treat long COVID respiratory complications.

Still, most experts caution these are early days and a one-size-fits-all therapeutic may not be possible.

Collaboration as key

Collaboration is seen by many experts as being key to solving some of the disease’s riddles. Yet Cheung believes that will only happen if we can get the provinces to share more information.

“I think, in general, it would be great for even more sharing across the country,” she said. “But because the health-care system is provincial, everything is done at a provincial level.”

Levin agrees, but in the current excitement to learn more about the disease, she also cautions against prematurely sharing data that might be misleading.

The mysteries around long COVID, what causes it and how the symptoms affect so many parts of the body requires a more fulsome assessment from specialists in all fields.

This is already happening in patients with other complex health issues. But according to Levin, the sheer number of long COVID patients means that, in time, this interdisciplinary approach to medicine may become the new normal.

“I think this is the beginning of perhaps a change in the way we look at health care and how best to integrate care and research in the moment — so that we can actually do the best for the patients,” she said.

For Derek Christie, his COVID recovery remains his singular goal. He’s confident he will eventually walk without a walker and return to his two loves: music and volunteering.

Meanwhile, Katy McLean has learned, through physiotherapy, to pace herself and manage her heart rate, which has been critical in controlling her symptoms. She too remains cautiously optimistic.

“It’s hard to know if things are going to get better or worse or just continue to go up and down like a roller-coaster,” she said.

For the doctors and other medical experts, they expect the sleuthing will never stop.

Almost two years ago, they faced a mystifying constellation of symptoms they didn’t understand. Cheung compared it to 10 blind men feeling an elephant. Now the picture is becoming clearer with better tests, which she hopes will soon become clinically available.

“Hopefully some of these things will become standard of care. But it takes a little time to get there.”

Article From: CBC

Author: Marcy Cuttler