When LGBTQ communities helped researchers turn HIV from a death sentence into a chronic illness, they gained a new perspective on risk, social stigma and the duty of care – insights that are still critical now

As COVID-19 hospitalizations decline and restrictions loosen across the country, boosted Canadians are slowly moving beyond the crisis stage of the pandemic. But a new phase brings new questions: What does it mean for a population to “live with” COVID-19, in the long term? What can be done to temper the social divisions that persist around this virus? How do we deal with its lingering effects, including long COVID? Two years since the pandemic took hold, how do we calibrate risk and function alongside it?

One population has significant experience with similar questions: gay men who either came of age during the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1990s or adapted in subsequent generations. Though SARS-CoV-2 and HIV have different transmission modes, courses of illness, outcomes and social implications, those who lived through the sweeping, devastating AIDS epidemic can offer insight on how to think about illness, consider risk and safeguard others, while allowing in relief as we begin to emerge.

Amid the AIDS crisis, there was a sense of responsibility for the well-being of others: Community members launched PSA campaigns and created mutual-care networks for the ill and isolated. While accepting a life of precautions, they advocated vociferously for treatment and prevention.

With the advent of antiretroviral drugs in Canada in 1996, HIV became a chronic, manageable illness for those with access to the treatments, which can suppress viral loads to the point that the virus becomes undetectable and untransmissible. On the prevention front, PrEP (preexposure prophylaxis) significantly decreases the risk of infection among the HIV-negative. The groundbreaking drugs have helped this community to navigate risk.

Those who remember the early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis saw parallels in the fear, panic and large-scale disruption of COVID-19′s first wave. Today, inequalities drive both AIDS and COVID-19, with access to costly antiretroviral treatments and vaccines still denied to many of the most vulnerable globally. Approximately 680,000 people died of AIDS-related illness worldwide in 2020, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

With many people diagnosed with HIV decades ago, there has been time to develop a “community sense of going through something together,” according to Ken Monteith, executive director of COCQ-SIDA, the Quebec coalition of AIDS organizations.

Mr. Monteith came of age during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Canada; he was diagnosed in the late ’90s. Recalling the early years, he pointed to a hostile health system that left at-risk groups and their supporters organizing themselves. “Faced with government indifference and silence, they had their own networks to transmit information,” Mr. Monteith said.

That included early advocacy for condoms, a pragmatic strategy that came from gay men themselves, he said. “Sometimes the practical, useful answers are in the community – not only from public health experts.”

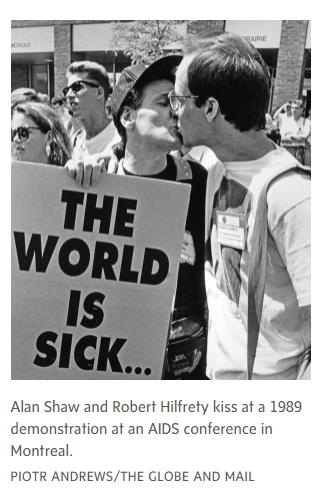

Art became an integral tool to raise awareness, reduce stigma, protest government inaction and educate the public about HIV prevention. Many of the creative campaigns were direct about risk but also arch in tone and forthright about sex.

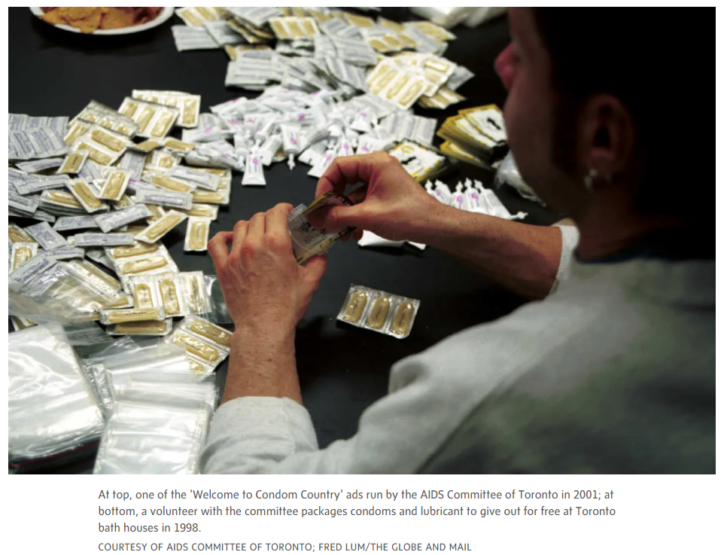

Artist Keith Haring, who died of AIDS-related complications at 31, created safe-sex campaigns in the late eighties: One 1989 artwork, Stop AIDS, featured twoentwined bodies forming scissors slicing through a snake, metaphorical for the virus. The same year, Gran Fury, a New York group of artist activists combatting AIDS stigma in the general population, organized a provocative campaignthat included bus and subway ads and a mass mailing of postcards featuring sexually diverse couples kissing. The message on the cards read, “Kissing doesn’t kill, greed and indifference do. Corporate greed, government inaction and public indifference make AIDS a political crisis.” Meanwhile in Canada, the AIDS Committee of Toronto (ACT) launched a poster campaign referencing vintage Marlboro ads: “Welcome to Condom Country. Ride Safely,” the spots read.

Community response extended to bars, clubs, bathhouses and sex clubs, which offered bowls of free condoms and educational pamphlets, with some also providing on-site testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

ACT would hold monthly parties where volunteers assembled packages of condoms, lubricants and sexual-health leaflets to be distributed free at clinics, book stores and clubs across Toronto.

Mr. Monteith saw some parallels of community response during COVID-19, when local activists knocked on neighbours’ doors to address vaccine hesitancy. “They know how to talk to them and identify the sources of these hesitancies, to be able to strategize. It’s not about excluding public health but about working with them to say, ‘Here’s what we have to overcome.’”

The HIV/AIDS community also demanded a seat at the table with the medical industry, significantly strengthening the role of patients in health care.

They pushed for early access to clinical trials, a wide array of treatment options and changes to drug regulation, while demanding that efficacy and side effects be closely monitored as the drugs went to market – effectively pioneering patient-centred care.

“In the eighties, we treated the emerging effects of HIV – the tumours, cancer, Kaposi sarcoma – but we weren’t getting to the cause of it. Only when the patient groups came together and said, ‘Nothing about us without us’ – this was the turning point. Everything was recentred on a person living with HIV,” said Gary Lacasse, Montreal-basedexecutive director of the Canadian AIDS Society.

Today, there are similarities between the early, panicked days of HIV and the many unknowns surrounding long COVID, according to John MacLeod, a family physician who has focused on HIV care since 1989, first in Montreal and later in Toronto.

After some health care providers initially dismissed long COVID as mere anxiety, sufferers began forming private networks of help, including numerous support groups on Facebook, where “long haulers” pushed for studies.

As with HIV, “the community came together and formed these groups to try and make things happen, to put together some research to make what they’re experiencing more credible so people would pay attention,” Dr. MacLeod said. “In time, there was interest in long COVID and some clinics popping up along the way.”

With the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, Dr. MacLeod fell acutely ill with a severe flu and shortness of breath. What followed was two years of intense chest pains, fluctuating oxygen levels and numerous visits to the emergency department and various specialists. He went from running half marathons and lifting weights five days a week to having to nap 10 times a day.

Though an MRI turned up viral myocarditis, the doctor never tested positive for SARS-CoV-2or its antibodies – a point that added to the frustration.

“All along with HIV, people had to figure out how they’re going to live with this. … In a lot of ways, long COVID is like that too. How do we live with the unknown, and who will give us support to do that?” Dr. MacLeod said.

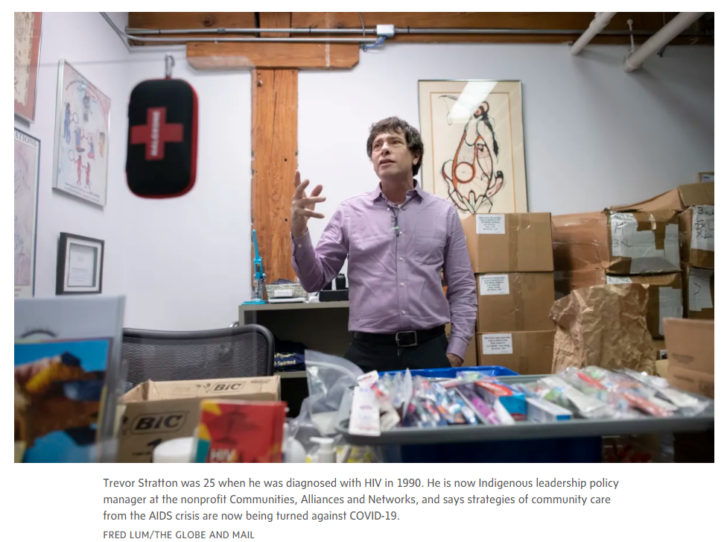

Diagnosed with HIV in 1990 when he was 25 years old, Trevor Stratton watched terrified as people all around him died. With many of the sick ostracized by their families, AIDS service organizations run by gay and lesbian communities were formed to improve conditions for dying people. Informal groups of friends and strangers also stepped in, setting up care teams to help the ill.

“Many people died alone. We decided this was not okay for people to be rejected,” said Mr. Stratton, who is theIndigenous leadership policy manager at Communities, Alliances and Networks, a non-profit organization that began as the Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network in the nineties.

“We had schedules and everyone would check off a box. We’d bring food. We were washing them. We’d communicate with their families and help them write living wills. We’d hold their hands as they were dying, saying, ‘It’s okay for you to go,’” said Mr. Stratton, who credits the antiretroviral drugs he began taking in 1999 with getting him off his death bed and back to work.

Today, Mr. Stratton, who is Indigenous and two spirit, said his community is applying those crisis skills to COVID-19. He pointed to the Toronto AIDS services organization 2-Spirited People of the 1st Nations, where he is president of the board of directors.

Throughout the pandemic, staff at the organization checked in on people, delivered food and harm reduction supplies and provided mental health aid. If someone was sick and alone at home or in hospital, they contacted family. For some clients, staff assisted with technology: They set up Zoom, handed out tablets, increased people’s bandwidth and topped up data packages so Elders could connect with others in lockdown. “Community’s going to figure out what works in their own families and circles,” Mr. Stratton said.

While such community networking proved effective through both the HIV and COVID-19 pandemics, broader messaging from public health officials too frequently fell flat in both cases, according to Mr. Monteith. Over the past two years, he was disheartened by the inconsistent, sometimes draconian decrees coming from provincial governments – particularly the concept of “social distancing,” which should have stressed physical space instead.

“We learned over time from HIV that punishing is not a good public health tool,” said Mr. Monteith, adding, “I’ve been seeing lessons not learned and it’s very disappointing.”

He referenced fines issued around gathering limits in the early days of COVID-19. “As usual, the tickets came down on the heads of people who have no choices and no means,” said Mr. Monteith, pointing to fears among people trying to access harm reduction sites at night during Quebec’s curfews.

Mr. Monteith urged deeper consideration for different populations and more transparent communication to bring the public along. “Over time with HIV we learned that fear messages ended up stigmatizing people who were living with HIV, while not really achieving any prevention goals. What becomes more effective is explaining – ‘vulgarizing,’ as we say in French – the science. It’s communicating to people who are not scientists so that they can understand these public health decisions.”

This still applies, he said, as provinces lift restrictions and jettison vaccine passports and mandatory masking – even as the Omicron subvariant BA.2 takes hold amid an absence of widespread PCR testing.

“We’re being told to ‘live with it’ without having the safety nets underneath us. It’s disingenuous for governments to back out of the controls that we put in to keep us safe without telling us, ‘This is what it’s going to look like and how you’re going to be affected,’” Mr. Lacasse said.

With COVID-19 being relatively new and so highly infectious, risk calibration remains complex, he added. It took several decades to mitigate HIV risk, through strategies that included condom-wearing, the development of antiretrovirals and PrEP, as well as honest conversations with sexual partners.

Shaun Proulx was diagnosed in 2005 but is now undetectable thanks to effective antiretroviral treatment. Mr. Proulx described the considerations some gay men made as they weighed potential partners’ tolerance for risk. “The community is a small one. You would find out who took a lot of risks and maybe you didn’t necessarily want to engage sexually with them. You made a probability analysis that they could be of higher risk to you,” said Mr. Proulx, a Toronto board member of Realize Canada, a national charitable organization that responds to the rehabilitation needs of people living with HIV/AIDS.

Now, with everyone vulnerable to COVID-19, risk calculus has become universal: “We’re making choices about, ‘Do I want to go to a restaurant that’s being opened up again with people who are eating and talking? Or do I want to stay in?’” Mr. Proulx said. Amid the endless decision-making, there should be some respite afforded to those who’ve taken precautions, he added. “I’m triple vaccinated. At some point, you have to claim your life back. That might not look exactly the same as it did before. You might have to cut off some people or make choices that you wouldn’t have had to before.”

Risk management evolves with scientific knowledge, which is in its early days with COVID-19, Mr. Monteith said. “It’s a disease that transmits extremely easily so the precautions are things we have to keep learning about; the goalposts keep moving,” he said.

“We will learn along the way how to manage it because people want to enjoy life and you can’t always live in fear. … We manage risks all the time, in every aspect of our lives, and this is something we will learn to manage.”

With a growing sense of emergence from the pandemic, this will be a time of reflection for those lost, said Albert McLeod,a long-time HIV activist and two-spirit knowledge keeper from Winnipeg. “How do we restructure our lives with that reality? That’s similar to HIV. We are survivors of that generation.”

In Manitoba, Mr. McLeod is working on a quilt project memorializing those who died during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many in their circles weren’t given rituals for closure, with the sick suffering alone in intensive care units and some families barred from holding proper wakes, funerals and burials. “There’s all this unresolved trauma and loss that’s happened to Canadians in the last two years,” he said.

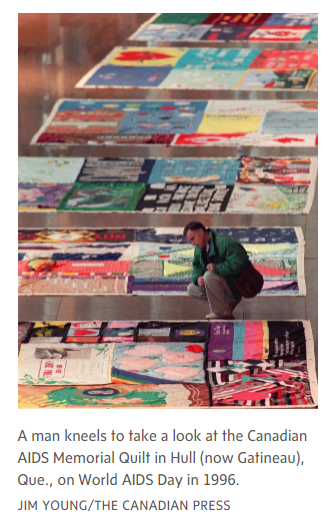

The project references the Canadian AIDS Memorial Quilt, which is comprised of about 600 panels, each memorializing an individual or group of people who died of AIDS-related causes. Throughout the eighties and early nineties, many were disowned by bigoted relatives, denied proper funerals or buried far from home. “The quilts came about because undertakers would not bury people dying of AIDS at the beginning of the epidemic. So families and friends of people who died of AIDS made a quilt panel in 12-foot sections. They were the same size as a coffin,” Mr. Lacasse said.

The colourful panels feature people’s names, birth and death dates, messages and artwork from those who loved them. As a communal symbol of grief, the quilts were publicly displayed over the years and now reside with the Canadian AIDS Society.

The planned COVID-19 quilting project will include a website where families can build a quilt digitally, or take online tutorials to sew a fabric version.

“If you’re sitting around a table sewing, that’s the healing component because you talk,” Mr. McLeod said. “It’s important to memorialize what occurred. Memorial makes us human. We’re not just pushing forward and saying it’s over, it’s done with.”

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: ZOSIA BIELSKI