Covid has revealed deep tensions within the medical community

An emergency-room (er) consultant in his late 40s enters a treatment room. He’s wiry and watchful, like a pit boss in a casino. “Hi Ma’am. So, what’s going on?” he says, using the friendly, open voice he’s honed over the years. We’ll call him Dr Croc for anonymity, an alter ego derived from his nickname, “Doc Crocodile”, which, he says, refers to his own “cold, dead reptilian heart”.

The patient is a woman in her mid-60s. She is deferential, her voice laced with worry. Her 40-something daughter sits at her side.

“I hurt when I breathe.”

“OK,” Croc says, reviewing her symptoms. She’s had a fever for three days and has a cough.

“Did you get vaccinated against covid?”

“No.”

“Is there a reason you didn’t get vaccinated?”

“Laziness,” she says in a near-whisper.

“Uh-oh.”

It’s the kind of non-judgmental “uh-oh” you’d rattle off if your child told you she’d lost a sock. But Croc is worried: she’s unvaccinated, almost certainly has covid and needs to be admitted for supplemental oxygen.

Croc splits his time between two hospitals in California. This one is close to the Bay Area, a region populated by farm workers, many undocumented, and well-educated, liberal-leaning professionals, among others. More than 75% of residents in the county are fully vaccinated, higher than in California overall.

The other hospital where Croc works is in the Central Valley, a patchwork of counties that Donald Trump either won easily in 2020 or lost by only a narrow margin. Mirroring the Republican-Democrat divide in vaccination rates across America, the share of inoculated people in this area is well below the state average; many locals oppose getting the jab.

“Don’t come to work and think you can, like, cherry-pick around the covid patients”

Away from his patients Croc is full of bluster, which helps to alleviate the pressure of the job: the er is a “fast-moving river of shit”, his patients can be “fucking idiots” and anti-vaxxers are “fucking insane”. Certain other mental tricks also help him. “I may think, You’re unvaxxed and now you’re deathly sick, but no matter how much that fills my rage field, you were once a cute baby like all of us.”

Now he is treating a woman who has spent decades working hard to provide for her family but attributes her lack of vaccination to “laziness”. That’s a new one, Croc thinks.

He asks her if she’s had any exposure to the virus.

“My family,” she replies meekly.

“Well, that’s concerning,” he says. The woman’s son is already in the hospital’s intensive-care unit, with covid. Unvaccinated, he’d been put on a ventilator the night before and wouldn’t survive the morning. She would never get the chance to say goodbye to him. He was in his early 40s.

As Croc finishes the exam, he tells the woman they’ll check her for covid and for “other possibilities” too. “We’re gonna take care of you.”

Croc utters that reassuring refrain a dozen times a day, but on occasion his caustic side breaks through. He recalls walking into an isolation room to examine a 39-year-old unvaxxed man who’d been brought in, gasping for breath with a critical case of covid. “He was wearing one of those anti-vax ‘Live free or die’ t-shirts. I just said, ‘I see you made your choice.’ He was already so far gone he couldn’t hear me.” The patient died two hours later.

The daughter of the 60-something patient says that she is vaccinated. What about the rest of the family? “None of my three boys is vaccinated. Nine days ago, they all tested positive for covid. So did I. My father, he’s also got covid.”

There is a long pause, during which Croc adds it up: in front of him is a woman who is about to be admitted to hospital, her husband is home with covid and her son is gravely ill with the disease in the icu. Her daughter and her three grandsons have all tested positive.

“In the ER we are used to people’s idiocy. To have us be the idiots is shocking”

“The kids are afraid of the side-effects because they want to have babies. The older one, he thinks that the vaccine is really bad. I told him we’ve been guinea pigs to vaccines all our lives. It’s nothing new. Yeah, we might have some kind of side-effect, some kind of allergy to it, but it’s not something that can’t get, you know, fixed.”

“Exactly,” Croc says.

“My younger two, they’re just like, ‘We don’t have to have it, and we don’t want it’.”

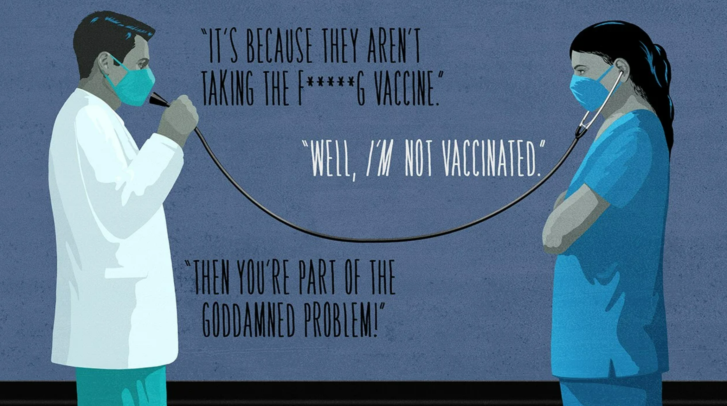

One especially hairy Saturday night last summer, when the er at the coastal hospital was packed with covid patients, Croc started to commiserate – or so he thought – with an er technician who was grumbling about the crowd.

“It’s because they aren’t fucking taking the vaccine,” Croc said.

“Well, I’m not vaccinated,” she replied.

“Then you’re part of the goddamned problem!”

The technician complained to the hospital administration, Croc says, and he was given an official reprimand. Croc knows he should have kept his mouth shut, but he’s found himself overwhelmed by the new reality. “In the er we are used to people’s idiocy – we sit around joking about it to relieve stress. To have us be the idiots is shocking.”

Many nurses at the Central Valley hospital were refusing the vaccine last summer, Croc says – some on the basis of political or religious beliefs, but he reckons others did so out of antagonism towards the medical establishment. “They feel undervalued and overworked. They say, ‘Don’t tell me what to do’ as a way of having their own agency.”

Croc, who has never had covid, got the vaccine as soon as it became available to health-care workers in December 2020. Since California made the jab compulsory for all medical staff in September 2021, hospitals are reporting that staff inoculation rates are above 95%. The state was among the first to require its 2m health-care workers to get a booster by the start of February.

Covid has brought other tensions in American medicine to the fore. Early in the pandemic, the coastal hospital where Croc works set up tents in the car park to examine those with suspected covid. Physician assistants, who have less training than doctors, were expected to staff the tents. Physician assistants often complain that they’re given the twisted ankles and sniffles while doctors keep the more “interesting”, complicated cases to themselves. (“That’s understandable”, Croc says, “because the docs should be reserved to take care of the sicker patients.”)

In this instance, however, assistants were incensed about the opposite: though doctors insisted that treating the tent patients was simple because they just needed to be tested for covid, the assistants “were like, ‘Oh, sure now you’re happy to give us the most high-risk patients, the people with this unknown, super scary infection.’ ”

Dissent intensified, Croc says, when some doctors refused to enter what came to be called the “dirty tent”. “Out of ten docs, you’d have three actively avoiding covid patients. A few others would try to be more subtle, like they’d suddenly get all interested in something going on away from the covid patients.” The hospital’s official stance was that medics couldn’t be forced to attend to any particular patient. (American hospitals often have contracts with external organisations to staff ers, which can muddy the lines of authority.)

“So some of the er docs had to mob up on other er docs. We’d take aside a doc who was avoiding covid patients and be like: ‘You fucker, this is the job. You don’t want it, then get out. Don’t come to work and think you can cherry-pick around the covid patients.’ ”

“There were a lot of cowards. Covid has been a real stress test for the profession”

Croc has little time for the gauzy videos from 2020 of noble medical staff confronting covid. “There were a lot of cowards. Back in world war one and world war two, you know why the officer carried a sidearm? It wasn’t for the enemy. It was for someone who wouldn’t go up and over, who wouldn’t answer the call. Covid has been a real stress test for the profession. And, honestly, we’d gotten kind of soft.”

Croc’s route from studying at Harvard to becoming a fully fledged doctor wasn’t a straight one. He did stints as a bike messenger (which he describes as its own form of street combat) and spent time as a paramedic in South Central Los Angeles and Africa. He did two “horrible things” early in his career that still prey on him, he says. As an emergency medical technician, he says, he was called to a scene where a mother and father had beaten up a friend they’d asked to babysit – they came home to find him raping their 12-year-old daughter. “I’m riding with the guy in the back of the ambulance”, Croc says, “and he’s telling me how good the sex was with this girl. He’s just bragging about it. So I fucking beat the shit out of that guy before we got to the hospital.”

Another time, “in an er in New Orleans I was treating a murder suspect who had a broken leg. Some cops came in to question him and they squeezed his fracture and twisted it. I was like, whoa! And the captain says ‘What did you see, doc? Nothing.’

“And you know what I did? Nothing. I feel worse about the guy with the fracture. On the first, I gave in to animalistic anger. On the second, I had a choice of stopping it,” he said. “Before it happened, I would have said I’d stop it, but in the moment I did nothing. That gives me empathy for making bad decisions, and realising that you’re just as fallible as the guy who’s lying in the hospital bed who may have made his own bad choices.”

ERS brim with people who, apart from failing to get covid vaccines, have made what are often conceived of as “bad choices”: they smoke, are obese or ski on unmarked trails. “I can think, You’re a drunk, stupid meth addict,” Croc says, “but my job is: how can I reach this person?”

He has tried various gambits to persuade people to get vaccinated. An interaction with an anti-vax couple sticks with him. When he delivered the news that their little girl, who was too young to qualify for the vaccine, had covid, “the dad said I was full of shit and wanted to see another doctor. I said, ‘Look, sometimes there are laboratory errors, so let’s do the tests again.’ He said ‘fine.’ The tests again came back positive, and I told him he could choose to believe it or not, but they’d come to the hospital so obviously they hoped we could offer them something.” The best thing the couple could do now for their child was to get vaccinated – they could do it that very day at the hospital, Croc added.

The father kept “grousing” so Croc tried another angle: “I know you care about your daughter because you brought her here in a car seat. Getting the vaccine is also showing you care.” The guy didn’t give an inch but later Croc discovered he’d gone right over and got the jab. “Holy shit!” Croc says delightedly. “Was it because I took extra time with him? Was it because I didn’t lecture him? Was it because I framed it in a way that left the decision up to his better nature?”

The challenge for him, Croc says, is working out how to give people “their moment”. He knows from his days as a bike messenger what it’s like to be invisible. Drivers didn’t see him – “so you make noise, you slap hoods, throw elbows” – and neither did the people who took his deliveries: “The secretary I hand the package to, it was like I didn’t exist.

“You realise how most people go through their whole life feeling completely unseen.” he says. “Before, my attitude was ‘I went to a slick private school, I went to Harvard, I’m a white man, so fuck you, you will see me!’ ” Now he’s different. But when he can’t find a way in, or work out how to offer a validating moment, Croc admits that he sometimes falls back on “bludgeoning” anti-vaxxers with data. “I’ll say ‘At this hospital 50% of unvaccinated patients who have been admitted die’, and so on. Then I leave them as if I don’t care.”

As suspected, the test results show that the woman in her 60s has covid. He doesn’t tell her that she also has pneumonia: “Why kick her when she’s down?” He calls her daughter to give her the full picture: her mother has been admitted but is so far requiring only a modest amount of supplemental oxygen.

“Oh, OK,” the daughter says, sounding resigned.

“And I know you’re vaccinated, thank goodness,” Doc says, staying crisp but friendly. “But with your mom now admitted and your brother in the icu, the rest of your family members should get vaccinated as soon as possible.”

“I know.”

After a long pause, the daughter asks what’s really on her mind: “How is my mother, really?”

“She’s OK, but she is sick. I hope we can keep her from getting more sick.”

“How will she do?”

“It’s hard to know. I think the next 24 to 48 hours are going to be the most important. We will keep our fingers crossed, and, you know, she’s in good hands.”

What will happen in the months ahead is anyone’s guess. Even now, Croc has no idea how many Omicron patients he’s seeing, as the hospital’s standard test doesn’t distinguish among strains. “It’s like being an astronomer: that light you see left the star aeons ago. We probably saw Omicron three months ago but didn’t realise it.”

As for his patient in her 60s, she was still in the hospital nearly two weeks after being admitted. Croc says she was “shattered” by the loss of her son but was hanging on. Her daughter reports that the three holdout grandsons have now all had their first jabs.■

Article From: The Economists

Author: RYAN VER BERKMOES

Ryan Ver Berkmoes is a writer who lives in California

ILLUSTRATIONS: MICHAEL GLENWOOD