Almost seven weeks after appointments opened, just 45 per cent of kids 5-11 had received at least one dose, as the date for in-person learning nears.

COVID-19 vaccine doses administered to the kids aged five to 11 in Ontario have dropped off significantly over the last three weeks, a sign that the province is facing an uphill battle to vaccinate even a majority of children in this age cohort before school returns to in-person learning.

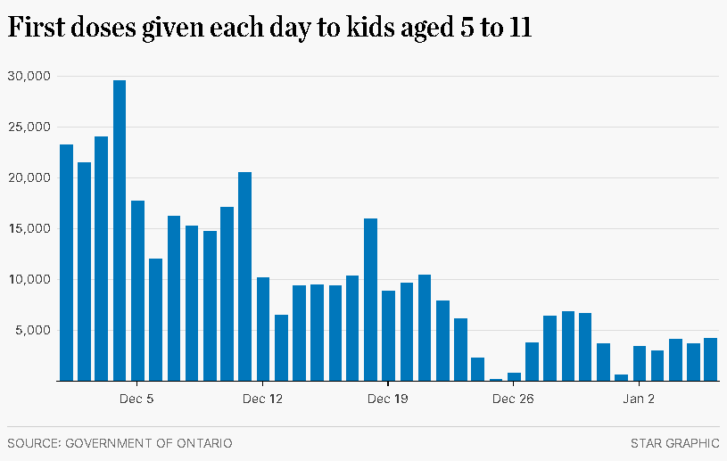

As of Thursday, almost seven weeks after appointments opened, just 45 per cent of kids in the five-to-11 age group had received at least one dose, according to provincial data, while the number of first doses given out has stalled at less than 5,000 a day in the last week.

“This is alarming,” said Peter Jüni, scientific director of Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. “Even though the risk of hospital admissions is still low in children, with so many infections happening right now it’s a numbers game. So it’s really important to get them fully vaccinated as soon as possible.”

He added that there is preliminary evidence suggesting that the advantages children seemed to have had with earlier variants when compared to adults are now disappearing due to Omicron finding easier ways to enter the cells of especially young children.

“It could well be that this difference that children are less affected than young adults is about to disappear.”

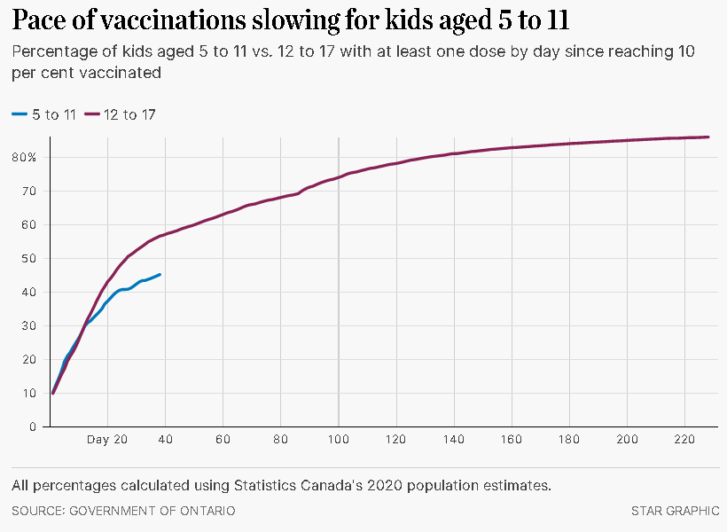

Right off the bat, five-to-11-year-olds and 12-to-17-year-olds saw comparable percentages of their respective populations getting vaccinated daily. (Vaccinations for the older cohort opened in late May.) Kids in the younger cohort became eligible for vaccinations Nov. 23, and while uptake was enthusiastic initially, it has trailed off.

New daily first doses for five-to-11-year-olds peaked Dec. 4 with nearly 30,000 shots given that day. Since then, the number of daily doses given out to this cohort has trended downward most days.

Dr. Dina Kulik, pediatrician and founder of KidCrew Medical, a multidisciplinary children’s health clinic in Toronto, said parents seem to be hesitant for two main reasons. The first is that they are scared of the vaccine because of misinformation spread on social media; the second is that there has been much publicity around Omicron being relatively mild and parents are therefore concluding their children are not at risk.

To address these concerns, Kulik explains that vaccines don’t tend to produce any negative long-term impact. “It’s been around for a year and a half, there’s no medium- to long-term side effects we’ve seen so far, nor reason to suspect there would be, because vaccines don’t typically cause long-term side effects,” she said.

“This argument that there might be long-term negative side effects to the vaccine, well, we know there are medium- to long-term negative side effects of COVID for children, even children who have very mild illness,” she added. “Even a child that has very mild illness with maybe no symptoms, or just a runny nose, has the risk of having brain fog, fatigue, mental health illness related to long COVID.”

Alex Hilkene, a spokesperson for Health Minister Christine Elliott, said the province knows that some parents might be hesitant to get their child vaccinated and may have questions.

“We also know that some parents may not want their child to get vaccinated at all,” she said in an email. “That’s why we are working closely with public health units, children’s hospitals, children’s services and other health experts, including partnering with SickKids to allow for confidential, convenient and accessible vaccine consultation services for children, youth and their families.”

For its part, the city of Toronto is setting up some 27 clinics in the next two weeks in an effort to get younger students, as well as education workers, vaccinated before the tentative return to in-class learning Jan. 17.

On Thursday, Mayor John Tory said only about 45 per cent of children five to 11 in the city had received their first dose, while 92 per cent in the 12-17 group had received at least one dose.

In early December a lot of kids came into community clinics in the Jane and Finch neighbourhood for vaccines, some with their parents or even grandparents, who joined them to get their first or second doses, said Michelle Dagnino, executive director of the Jane/Finch Community and Family Centre.

Since then, they have “certainly seen a drop-off” in the five-to-11 numbers. Some may be related to the Christmas break.

But Dagnino said the provincial booking system and complicated process to book at one of several pharmacies offering the vaccines are also barriers to some families, especially if the parents are shift workers or lack reliable schedules to book appointments weeks in advance.

She said she feels more targeted pop-ups aimed at families are needed on evenings and weekends, along with an education campaign.

“Really it’s an accessibility issue,” she said. “It’s the pop-up clinics which really have reached the vast majority of the population, and we haven’t seen the same amount of pop-up clinics for kids.”

To tackle this, the Jane and Finch Community and Family Centre and the Black Creek Community Health Centre are organizing three evening pop-up clinics later in January at the Jane Finch Mall, aimed at kids in the community and their family members.

Michelle Westin, a senior analyst of planning, quality and risk with Black Creek, said that only five per cent of doses at community clinics in the neighbourhood are now given to kids five to 11; the overwhelming majority are adults seeking third shots.

There has been some hesitancy from parents who are vaccinated but concerned about giving their young children the vaccine, she said. Clinics where they can ask questions, talk to medical professionals and community ambassadors in different languages can help, she noted, but that approach takes more time and trust.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach for any community,” she said.

Dr. Maria Muraca, a family physician and one of the primary care leads of North York Toronto Health Partners, said they saw two rushes of parents bringing their kids into family health team clinics.

The first was when the kids became eligible in late November. The second was when Omicron started exploding and media reports emerged about more kids ending up in the hospital. But “then it quickly died down again,” once the return to school was delayed, she said.

Her team is stepping up pediatric clinics, where kids get special certificates and loot bags with crayons and colouring pages, as well as providing resources to local schools. The mass vaccination clinic at Seneca’s Newnham Campus has also reopened.

Muraca urges parents to remember that most kids will probably be OK, but not vaccinating them is taking an unnecessary risk that amounts to a “roll of the dice.”

“These vaccines have been around for over a year now, billions of people have received doses,” she said.

“Consider this similar to all the other pediatric vaccines you gave your child and protect them from something you can protect them from.”

Article From: The Star

Authors: May Warren, Kenyon Wallace