The Star’s Megan Ogilvie and Steve Russell spent a day inside Mackenzie Richmond Hill Hospital to see the toll COVID has had on health workers.

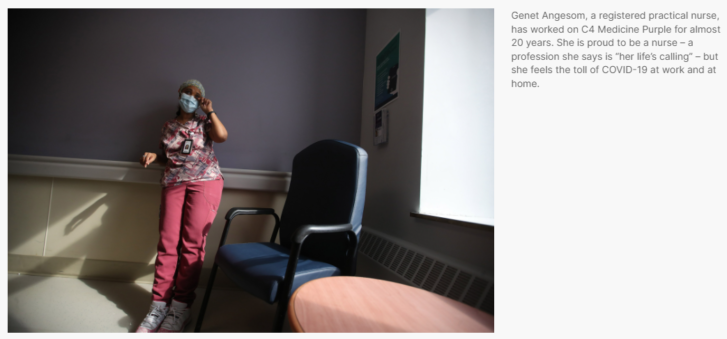

Genet Angesom weeps as she tells her story.

The registered practical nurse is standing at the end of the hall on the fourth floor of Mackenzie Richmond Hill Hospital, steps away from the patients she cares for on this medical unit.

It’s a typical day — there is no crisis — but the toll of the last two years is spilling out.

Wiping tears from her eyes, Angesom explains how the pandemic has made the difficult job of nursing even harder. There are more tasks, new worries, longer days.

She also details how COVID-19 has ravaged her family, starting in the first wave when the virus killed her older brother and severely sickened her husband, a personal support worker at a Toronto long-term-care facility.

Last year, when travel restrictions meant Angesom could not be with her father when he died in Eritrea, in northeast Africa, she was forced to mourn him at her Thornhill home.

And then, in January, at the height of the Omicron wave, Angesom got COVID — she believes she was infected during an outbreak at work — and needed three weeks to recover, despite being fully vaccinated.SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

“Our house,” she says, “it has been affected with so much sickness and death.”

But still, Angesom is here, caring for patients. She wants people to know that health-care workers, behind their uniforms, bear their own pandemic wounds.

“If you could see inside, you could see how much they struggle.”

The Star visited a general medicine unit at Mackenzie Richmond Hill Hospital in mid-February to see how health-care workers were coping following the devastating impact of the Omicron wave. The hospital admitted its first COVID patient on March 2, 2020 and has since been among the hardest-hit Toronto-area hospitals in the pandemic.

With COVID cases declining, and COVID wards clearing of the sickest patients, staff said they hoped the worst was behind them.

But they also spoke of their bone-deep fatigue after two years of pandemic medicine and the resilience needed to work through the trauma of multiple COVID waves.

Some described their frustration with the fraction of the public who demand the end of COVID protections and minimize the virus’ threats.

Most who spoke to the Star want people to understand COVID is far from over for those who work in hospitals, and recognize they are doing their best amid a never-ending stream of challenges at work and at home.

“I’m here to do my job; I’m proud of … working through a moment in history,” says Hannah Han, a registered nurse and the unit’s patient care co-ordinator.

“But we also have families. We’re mothers. We’re wives. We have elderly parents we care for. If you could send a message out to everyone (I’d like them to know) this is not easy, it is extremely challenging … but as health-care providers, we still give ourselves to our community.”

This medical unit, known as C4 Medicine Purple, has never been a COVID ward, though it usually does care for a handful of COVID patients.

It’s primarily a nephrology unit, meaning its patients have kidney disease or disorders, with many requiring dialysis. There is space for 28 patients and each needs complex nursing care.

Today C4 Purple is full, a point that comes up at the daily morning meeting where managers review the number of patients in each of the units and emergency departments at Mackenzie Health’s two hospitals and at the Reactivation Care Centre, a shared community facility for those who no longer need acute hospital care.

The Cortellucci Vaughan Hospital, which opened in February 2021 exclusively as a COVID hospital, and then last June as the region’s new community hospital, is part of Mackenzie Health.

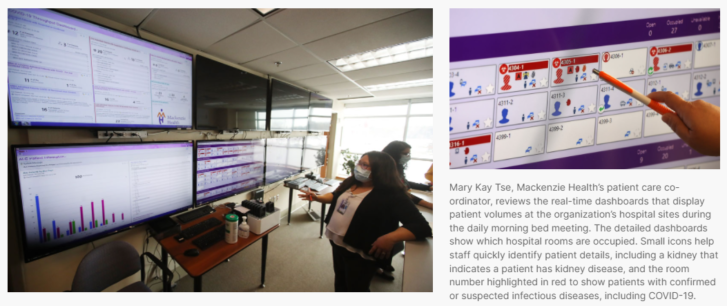

Mary Kay Tse, a patient care co-ordinator, takes notes during the 20-minute meeting. She listens as unit managers call in with updates on staffing concerns and the number of patients being admitted and discharged that day.

Behind her, a wall of TV screens display real-time dashboards that track patient volumes and the number of beds available on each unit. Staff also monitor the news, including COVID trends and traffic reports of highway crashes, to plan for patient surges.

The updates today are swift and to the point: The hospital system is at 96 per cent capacity. Its emergency departments were busy overnight, and they are nearing the limits of staffed ICU beds. There are 22 COVID-positive patients and 25 patients suspected of having the virus. Staffing is a concern, but manageable.

Moving 19 patients waiting in the Richmond Hill hospital’s ER to an in-patient bed is the most pressing problem. Three of these patients need to be in the ICU, including one who was recently intubated.

Despite this concern, Tse says today is “going to be OK. We’ll be able to meet the demand.”

Just weeks ago, in early January when Omicron was peaking in the province, few days were OK at Mackenzie Health.

The crush of patients combined with critical staffing shortages fuelled by the highly contagious variant meant each day was a scramble to find enough staff and enough beds, even after following the provincial directive to postpone scheduled surgeries. At the apex of Omicron, its two hospitals were caring for 131 COVID patients.

“It was very much crisis management,” says Mary-Agnes Wilson, chief nursing officer, COO and executive vice president at Mackenzie Health.

She noted that in the first 20 months of the pandemic about 540 staff were off for COVID-related reasons. But in one month, between Dec. 20 and Jan. 20 at the height of the Omicron surge, 544 staff were off because of the virus.

At that time, Mackenzie Health redeployed administrative staff to in-patient units to help with some tasks, such as delivering patient meals, to free up nurses for medical care.

And while extreme pressures had eased by mid-February, Wilson says operations were still nowhere near normal.

Working through the Omicron wave was especially tough on C4 Purple.

The unit was full of patients with complex medical conditions. Many staff were home, either sick with COVID or caring for family members ill with the virus, and those remaining needed to work longer hours and pick up extra shifts.

And as the variant tore through long-term-care facilities, triggering outbreaks, many patients on the unit could not be discharged to their retirement or nursing homes. That meant C4 Purple was caring for more than the usual number of patients with dementia, some with difficult-to-manage behaviours, at a time when staff were already stretched thin.

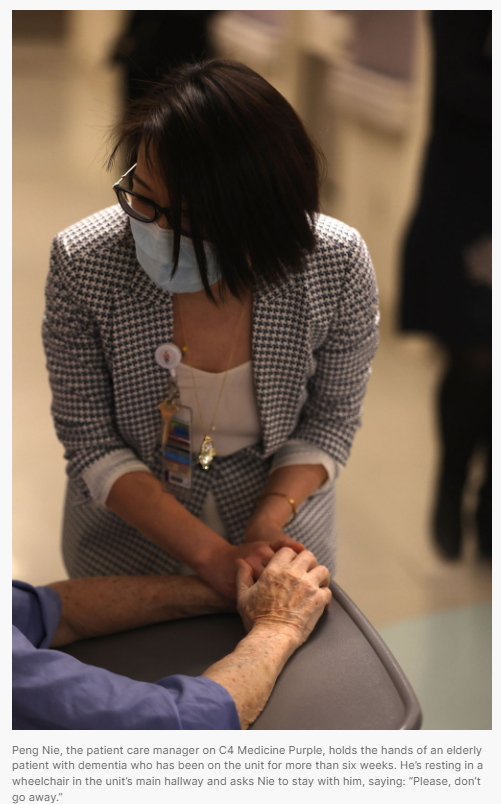

Peng Nie, a registered nurse and the unit’s patient care manager, explains all this as she walks along the main hallway.

She stops in front of a patient with dementia, who is sitting in a wheelchair near the central nursing station, a busy place he likes to watch during the day.

Nie leans in to ask how he is doing and whether he’d like to be wheeled around the unit. The patient, who has been on C4 Purple for more than six weeks, grasps her hands and says: “Please, don’t go away. I need somebody.”

She stays a few minutes longer, patting his hand and talking quietly.

“He’s been with us for about 45 days,” Nie says, watching a service assistant start to slowly wheel him around the unit. “We’re treating him like one of our own family members.”

Staff had to step in for family when the hospital system, as directed by the province, restricted visitors, starting on Dec. 23.

For 47days, up until Feb. 8, visitors were not allowed at Mackenzie Health except for some types of patients, and in specific circumstances, including when a patient was dying.

Visitor restrictions tightened even further when a COVID outbreak hit C4 Purple on Jan. 13.

Nie says the outbreak started in a ward room when a patient, who initially was asymptomatic and tested negative for the virus, developed symptoms, leading to a second patient in the room getting the virus.

The outbreak — declared over on Jan. 22 — led to three patients testing positive for COVID. Eight staff also had the virus at that time, though Nie says it wasn’t clear whether they got infected at the hospital or in the community.

“Any unit on outbreak, patients can’t have visitors, and if (patients) used to walk around, they are confined to their room,” Nie says. “This is very challenging for our (dementia) patients. We do see their behaviour getting worse.”

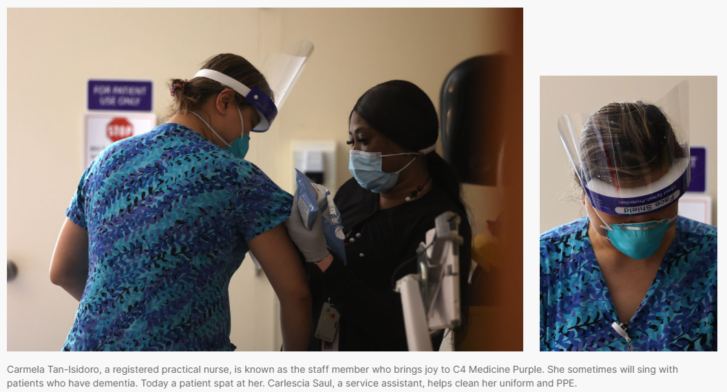

Carmela Tan-Isidoro, a registered practical nurse, often takes extra care with patients, especially those who are frail or who have dementia or age-related memory loss.

“When I can, I try to stay with them for a little bit, maybe hold their hands, maybe talk a little bit,” she says.

Sometimes, she will sing. Though her voice is muffled from her mask, Tan-Isidoro says she can tell that simple songs — ‘You Are My Sunshine’ is her favourite — can calm an agitated patient or help another to smile.

“This kind of care, it comes straight from our hearts.”

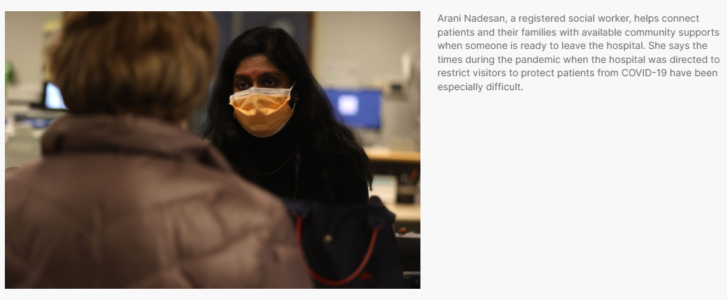

Not having family at the bedside was among the biggest challenges the unit faced during the Omicron wave, says Arani Nadesan, a registered social worker.

Visitors help with meals, ease patients out of bed for short walks and provide welcome distractions during an isolating time.

It’s been heartbreaking to see patients miss their family, Nadesan says, especially those who have weeks-long hospital stays. She wants people to know that COVID affects everyone who comes to hospital, not just those with the virus.

“You don’t want to end up in a situation where you’re limited in seeing your loved ones during the worst times of their life, right? Because that’s what (being in) the hospital is — the worst time of your life.”

Nadesan, who is 29 and started her job during the pandemic, helps connect patients and their families with community supports when someone is ready to leave the hospital. She also speaks with those whose loved one has died in hospital. Little, she says, helps ease their devastation about not being at the bedside to say goodbye.

She says working in the hospital, facing so much grief, has made it difficult to fully join in with friends’ celebrations and to enjoy life as a young person in their 20s.

“We’re here, breaking families’ hearts, every day,” Nadesan says. “The dichotomy of leaving and seeing people not following COVID regulations, and then having to come back to the hospital and having loved ones cry and cry over the phone … it’s just something I’ll never forget.”

The staff in Mackenzie Health’s Patient Relations department also know how much families struggle when they can’t be at bedsides. Christina Wright, manager of patient experience, says visitor restrictions — either ones imposed by the province during COVID surges, or those due to a hospital outbreak — almost always lead to an influx of calls and emails to her department.

That the hospital system requires visitors to be fully vaccinated to see most patients — a measure to protect the vulnerable in their care — also angers some people, says Wright, noting the pandemic has led to “far more intense emotions.”

The four-member team aims to mediate between care providers and a patient or their family to help clarify a situation or resolve a conflict. Wright says she starts most conversations by asking, “Help me understand what happened” to allow people to tell their side of the story.

But in recent months, she says, few people who call patient relations are interested in having an open conversation. Rather, they want to vent their anger and frustration. Though these are valid emotions during a stressful time, Wright says those interactions, some of which are threatening, leave her and her staff feeling depleted and upset.

She wants the community to understand that hospital workers are trying — just like them — to make it to the end of the COVID marathon.

“We want to get there in one piece, feeling like a whole human being,” says Wright. “I think as health-care professionals, people sometimes forget that we’re human, too.”

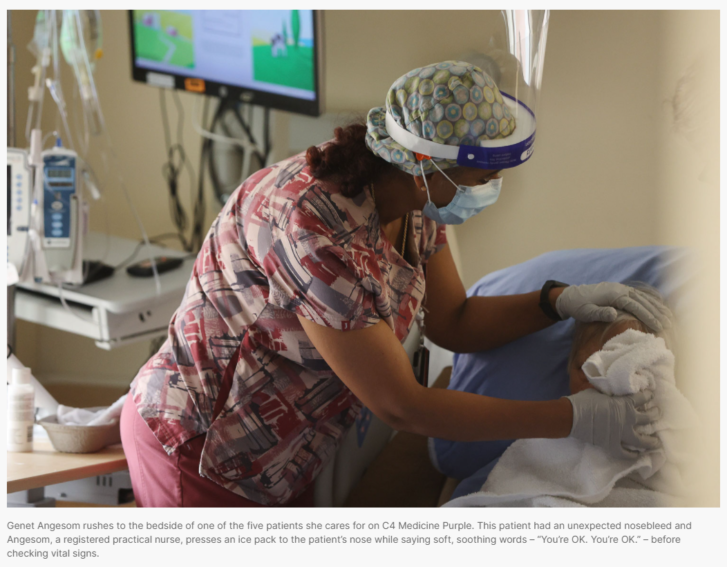

This is the point Angesom makes as she talks through the pain of the pandemic.

Before she can finish her sentence, Angesom rushes to help one of the five patients in her care. She speaks softly to the patient, in distress from an unexpected nosebleed, as she presses an ice pack to her nose.

Later, when asked if she’s ever thought of giving up nursing given the hardships of the past two years, Angesom says sometimes, at the back of her mind, she considers the question.

But then she remembers how much she loves nursing — she says it’s her life’s calling — and that she is proud of her more than two-decade career.

“We’re here, helping others,” she says. “That’s how we’ll get through this.”

Article From: The Star

Author: By Megan OgilvieHealth Reporter

Photographer: Steve RussellStar