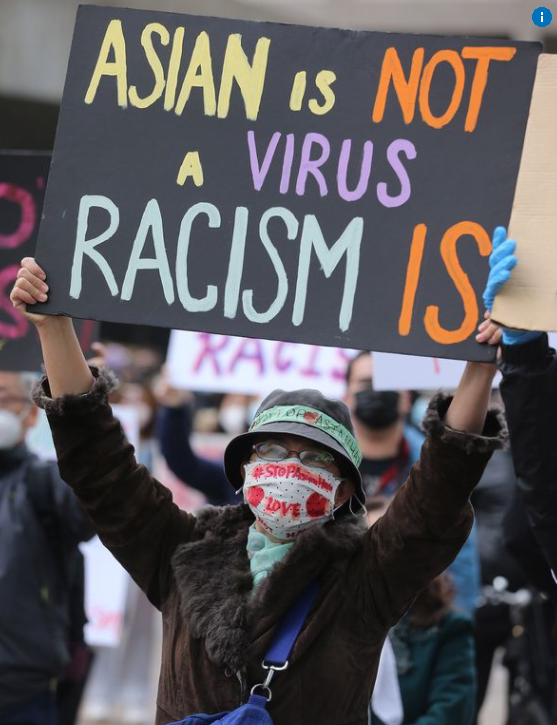

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese Canadians and other visible Asians became targets of threats and attacks in the nonsensical scapegoating of the coronavirus.

In 2020, the Chinese Canadian National Council Toronto Chapter (CCNCTO) and community partners across Canada documented 1150 cases of racist attacks nationally, with Vancouver seeing a 717 per cent increase in anti-Asian hate crimes. Asian elders have been especially targeted, including a 92-year-old man with dementia who was violently shoved onto the pavement in Vancouver and an 80-year-old woman who was assaulted and struck in the head with a rock in Pembroke.

A year and a half later, new anti-Asian racism cases continue to flood into Fight COVID Racism’s self-report and witness-report tracking tool.

While these are examples of overt, hate crimes, the type of racism that cannot be tracked, but continues to happen is the experience of someone like Michael. Michael is a Chinese Canadian who has worked in Chinese supermarkets for nine years. He has low pay, works long hours and faces the systemic violations of minimum wage and vacation pay. It is par for the course in this line of work. Michael’s situation is already far better than that of his co-workers who have precarious immigration status and endure worse treatment and exploitation.

When the pandemic hit, Michael saw his pay and hours reduced. He and other workers had to pay out-of-pocket for their own masks and even disinfectant to stay safe on the job and at home. Confronted with the financial squeeze and risk of infection at work, he also faced a growing anti-Asian sentiment outside of work due to racist scapegoating.

Michael’s experience, detailed in a new report Our Lives Are Essential by CCNCTO, is both recurrent and commonplace within Chinese Canadian working class communities, where precarious working conditions and endemic poverty are deep and persistent. Chinese Canadian communities experience conditions of low-income at rates nearly double that of white communities (22.2 per cent to 11.5 per cent), making up the largest population of racialized people living in poverty.

Racially-motivated hate is the most obvious manifestation of anti-Asian racism; the tip of the iceberg visible above water. Beneath the surface lies the far more subtle and insidious nature of racialized social and economic exclusion: elevated levels of poverty, racial disparities in employment, underinvestment in working-class communities, reduced access to health and social services, legally-produced immigration status precarity, reduced support for collective bargaining and more pronounced violations of workers’ rights. The hypervisibility of hate crimes and related calls for greater policing stand in stark contrast to the normalized indignities of racialized poverty and labour injustice.

This invisible side of anti-Asian racism often is erased by the “model minority” myth, which fixates on visible Asians who are wealthy, educated, and upwardly mobile, rather than the poor and marginalized. But the working-class genesis of the model minority trope originated more maliciously. When white settlers enlisted Chinese migrant workers in the 1880s to build the Canadian Pacific Railway, Chinese workers were seen as economic threats because of their supposed inherent “propensity” to be compliant, manageable, accepting of lower wages, longer hours, and dangerous work … all threats to white workers’ chances for prosperity.

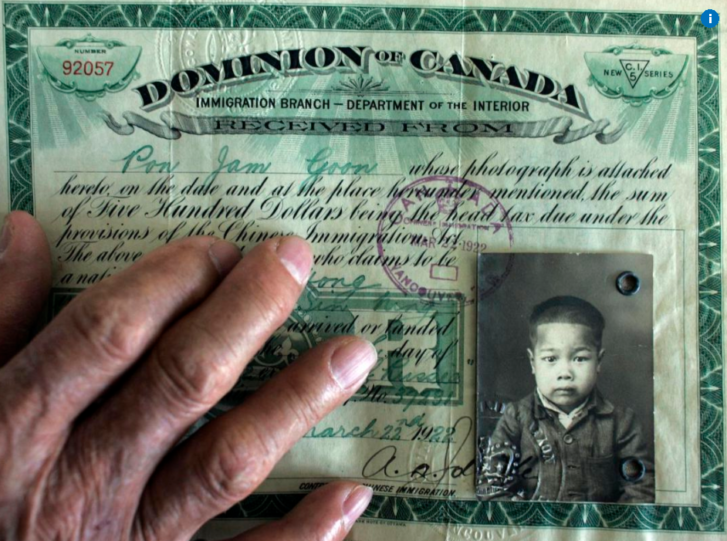

Operating parallel to the federal government’s imposition of racially exclusive policies, like the Chinese head taxes and immigration restrictions, were white labour unions that passed restrictions banning Chinese workers (and later Japanese and South Asian workers) from their ranks. The idea of the toiling Asian worker continues to manifest as a threat to Canadian labour to this day — with former Toronto Mayor Rob Ford infamously remarking “Oriental people work like dogs” and were “slowly taking over.”

The entanglements between worker exploitation and racial caricature of the Asian labourer has resulted in a host of anti-Asian racist harms: perpetual foreignness, immigration controls combined with racial exclusion, and the undermining of labour solidarity — limiting our capacity to see workers’ struggles as tied to struggles for racial and migrant justice.

As a result, the successes of Chinese Canadian labour organizing is also lost, from the strikes led by Chinese and other Asian shingle mill workers in British Columbia that predated the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, to the creation of the Ontario Employee Wage Protection Program in the 1990s after Chinese Canadian garment factory workers organized against wage theft by Lark Manufacturing.

Alongside anti-Asian racist attacks, a hierarchy of “essential” work has emerged during this pandemic. The invisible low wage labour that disproportionately relies on racialized immigrant workers in industries like food, transportation, personal support and more. Those jobs were first labelled non-essential, despite taking the front-line brunt of running establishments that supplied basic necessities to us during the series of lockdowns. This Labour Day, in the shadow of a federal election and another spike of COVID cases, the invisible side of anti-Asian racism hidden behind the model minority myth — valuing certain labour over others — must be made visible again.

Michael is not the only racialized immigrant low wage worker whose blood, sweat and tears remains ignored by our political system. So many have been made invisible and isolated in their labour struggles, while simultaneously made hypervisible by continued anti-Asian sentiment.

Only by seeing the labour and lives of racialized immigrant workers as essential to our communities will we recover towards a fair and just society for all.

Vincent Wong is a human rights lawyer and PhD student at Osgoode Hall Law School.Kennes Lin works as a community social worker and is the co-chair of the Chinese Canadian National Council Toronto Chapter.

Article From: The Star