Alan Bernstein is president and CEO of the global research organization CIFAR and a member of Canada’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force. Janet Rossant is president and scientific director of the Gairdner Foundation and senior scientist emeritus at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

To say that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of open science to humanity is the understatement of the century.

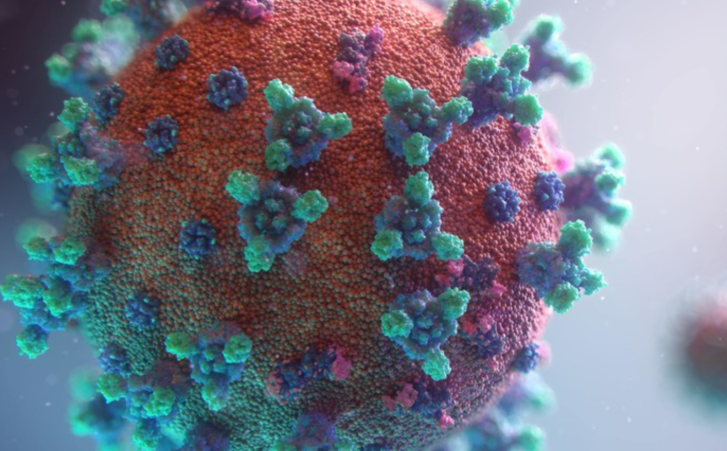

In January, 2020, scientists in China shared with the world the genetic sequence of the new coronavirus they had isolated from very sick patients in Wuhan. Since then, science has continued to provide an amazing arsenal with which to defeat the virus: PCR diagnostics, rapid antigen tests, vaccines made in record time, monoclonal antibody and novel drug treatments, and powerful new genomic surveillance tools to detect the emergence of dangerous viral variants and model the future course of the pandemic. The key to this remarkable list of achievements has been global collaboration, openness and rapid data sharing.

A more recent example of the power of open science was the identification of a new COVID-19 variant in southern Africa: Omicron. Scientists in South Africa were quick to share the discovery with the rest of the world. That’s the kind of action that has been key to our ability to fight this virus, and that must be encouraged.

And yet, soon after the World Health Organization declared Omicron a variant of concern, many countries, including Canada, restricted travel from southern Africa. Prolonged travel bans may buy time to put in place necessary public health measures, but they usually don’t work, because they typically come into being after a new variant is already circulating widely (as was the case for Omicron). Worse still, these specific bans had the effect of punishing the very countries that had alerted the world to Omicron in the first place.

The travel bans have now been reversed. But has the damage been done? Countries already suffering economically from COVID-19 restrictions may hesitate in the future to share the scientific information that has underpinned our successes in developing and testing vaccines, diagnostic tests and drugs.

The emergence of Omicron, and Delta before it, is a wake-up call to countries in the global North that they must renew efforts to ensure supply and access to COVID-19 vaccines in low-income countries. Increasing the percentage of the world’s population that is vaccinated against the virus is the best way to reduce the chance that more variants will emerge.

But vaccination alone isn’t enough. Genomic surveillance to detect and characterize new viral variants needs to be done everywhere in the world. In Canada, it is being undertaken in two national efforts: CanCoGen and CoVaRRnet. Rapid sharing of genomic and immunological data, combined with public health and clinical data and material, is essential if we are to answer key questions about Omicron or any new viral variant. How transmissible is it? Does it cause more or less severe disease than other variants? Are our vaccines still effective or are booster shots or new vaccines required? Which populations are most susceptible to serious outcomes from infection?

And yet, in Canada, bureaucratic hurdles often prevent health officials and policy-makers from getting reliable, real-time Canadian data on how COVID-19 is affecting public health across provincial boundaries. During normal times, it’s customary to be asked to complete various forms to receive data or biological material from an outside lab or clinic. But we are at war. Speed is of the essence and normal processes are no longer appropriate.

We need (suitably anonymized) data on the characteristics of who has been infected, such as their ages, vaccination statuses, genders and pre-existing health conditions. The data must be linked to clinical data on the severity and characteristics of the disease. Without any of this, we can only rely on reports from other countries with more generous data-sharing practices, whose information may or may not be relevant to Canada.

While our bank cards can access banking data and local currency anywhere we go, our health cards are still stuck in a world where fax machines and pens and pencils reign supreme. It’s in all our interests that the provinces sit down with Ottawa and finally agree to a health data-sharing agreement that brings our health and public health systems into the 21st century and allows us to fight this pandemic without our hands tied behind our backs.

The future course of this pandemic depends on science, global collaboration and rapid sharing of data. The health of Canadians depends on it.

Article From: Globe and Mail

Authors: ALAN BERNSTEIN AND JANET ROSSANT