On a mild day late last year, my husband and I were walking through High Park – Toronto’s 160-hectare urban oasis complete with a zoo, walking trails and its famous Grenadier Pond – when we stopped to look at a squirrel sitting on the trunk of a tree. It was making eye contact with us, and we remarked that it reminded us of our entertainingly dopey cats. Suddenly, two tiny squirrel paws, then a head, popped out from a hollow just beneath it. Now two squirrels were staring at us in puzzlement while we laughed at the unexpectedly comical moment.

Once the humour subsided, I mused about how there’s so little room for feeling surprise like that in our current circumstances. Of course, it’s likely none of us expected to still be in this fraught and uncertain situation, but living during a global pandemic means that life has a narrower scope and become largely bereft of the unanticipated moments we might encounter while travelling or out with a group of friends.

It turns out that a lack of surprise in our lives has important implications beyond contributing to a state of constant ennui. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in December, the co-authors – including Morgan Barense, professor and Canada Research Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Toronto – reveal that the event of surprise is linked to the currency and correctness of our memories.

“The brain is a fundamentally predictive organ,” Barense explains. It generates an internal model of the world and what it’s expecting to happen. But when those expectations are violated, when we’re surprised, our internal model needs to be updated. “There’s a big idea in memory research that when a prediction error is generated, it signals an ‘event boundary.’ Those boundaries are important for scaffolding and shaping our memories.”

In a TEDX Teen talk, Tania Luna, author of Surprise: Embrace the Unpredictable and Engineer the Unexpected and a former psychology instructor at Hunter College, discusses how, as we age, we begin to avoid unfamiliar or uncertain situations. This winds us into a place where relinquishing control, refusing to acknowledge our biases and the fear of being wrong dominate our mental direction. Surprise, on the other hand, allows us to create modes of curiosity and wonder.

These are certainly two sensations I’ve experienced while watching the HBO show How To with John Wilson, which, in addition to therecent super-Surrealist collections by French fashion house Schiaparelli, has been crucial to keeping me agog throughout the monotony of yet another stage of pandemic restrictions.

The engaging flow of clips and commentary in each episode, all strung together from an overwhelming bank of video footage Wilson has shot in New York, leaves me with perpetual “duh face” – what Luna dubs the expression we have when we’re surprised. And what I’ve come to learn is that Wilson’s ability to link together surprising moments of an abstract, whimsical, tense, mundane and even bleak nature actually forces me to recalibrate what I think I know about the world.

“I wanted to make something that was wall-to-wall some of the most unique imagery you could find,” Wilson said in an interview. “I get so much joy out of sharing these moments with people.” He adds that part of the reason he thinks the show is so compelling is that we’re “believing what [we’re] seeing but also not believing it – there’s something really exciting about that emotionally. I want that to remain a constant buzz throughout the work.”

And the buzz is mutual. When he describes gaining access to an energy drink mogul’s preposterous mansion and getting a glimpse of his outsized, amped up lifestyle, Wilson still sounds incredulous. “It was one of the most exhilarating moments of my life to encounter something like that,” he says. “That’s what I live for – this really risky thing worked out, and we’re seeing something that nobody has ever seen. It’s such a rush.”

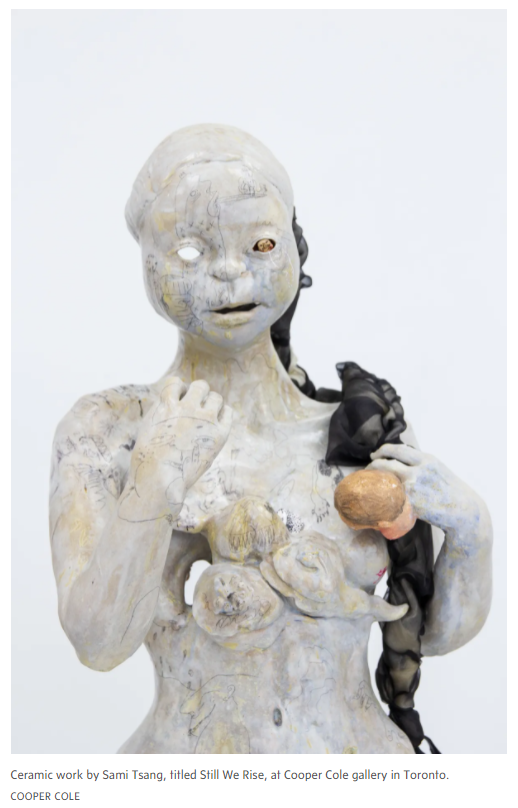

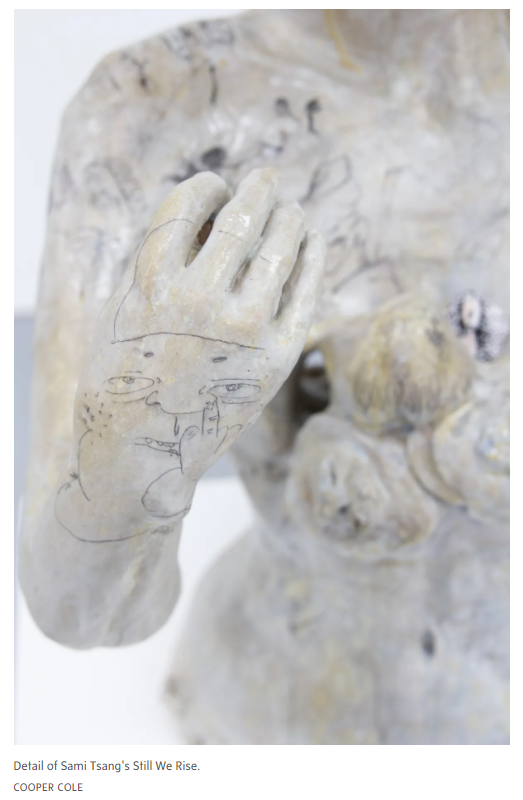

The last time I felt a rush (without the risk, mind you) was in January on the opening day of Toronto art gallery Cooper Cole’s latest exhibition, Separate/Together. While winding my way through the collection of pieces, I was taken aback by a ceramic work by Sami Tsang. Titled Still We Rise, it’s a female figure possessing a textile braid and boasting an assemblage of sketchbook-y drawings across her glazed frame; an assortment of faces protrude from various body parts as well.

It’s truly astonishing to gaze upon – I’d never seen anything like it – and I found myself circling around its plinth several times, gasping as each new detail came into my view. “My work talks about mystic encounters, private matters and inner struggle,” says Tsang, noting that her artistic practice deals with mental health. “These stories are drawn from myself or through intimate conversations with other people. And sometimes, [they’re] imaginary.”

Indeed, I recognized an element of fantasy permeating Tsang’s captivating sculpture. Coupled with the intimate tension she expresses, a haunting quality is exposed that lingers with you long after your eyes have left it. And what’s more, the sense of surprise the piece inspired in me – despite the fact I’d followed her work on Instagram for some time – roused such curiosity in Tsang’s art that I just had to know more about this young talent, who was the recipient of the Gardiner Museum Prize in 2019.

“I’m a pretty open person and I do share a lot of my personal story with people,” she says as we discuss the fact that while I couldn’t wait to see what my eyes came to next on her sculpture, I know other onlookers might not have that same zeal for examining the piece. But that doesn’t seem to bother Tsang.

“Over time, I’ve developed more of an instinct with what I want to share with people – who really cares, or if someone is listening but doesn’t really get it,” she says. “It’s similar with audiences of my work; some people will just walk past [it], and some people will really see it and what I’m trying to talk about with the piece without me having to suggest too much. When I find that connection, it’s so special.”

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: ODESSA PALOMA PARKER