Patricia Treble: The delayed response is part of a frustrating pandemic pattern in Canada, where governments fail to recognize the blindingly obvious

“You’re swearing a lot, Patricia,” a cousin recently observed. “I’ve been writing about the pandemic for nearly two years,” I responded, “It’s either a potty mouth or throwing something against a wall.”

If there is one issue that has amped up my vocabulary, it’s the slow rollout of rapid antigen tests (RATs) to the general population in this country, especially my home province of Ontario. I’ve been writing about rapid testing since December 2020 and only now, 515,000 cases of COVID, and 6,400 deaths later, is the provincial government distributing some free home tests to everyone. No wonder #FreeTheRATs keeps trending on social media.

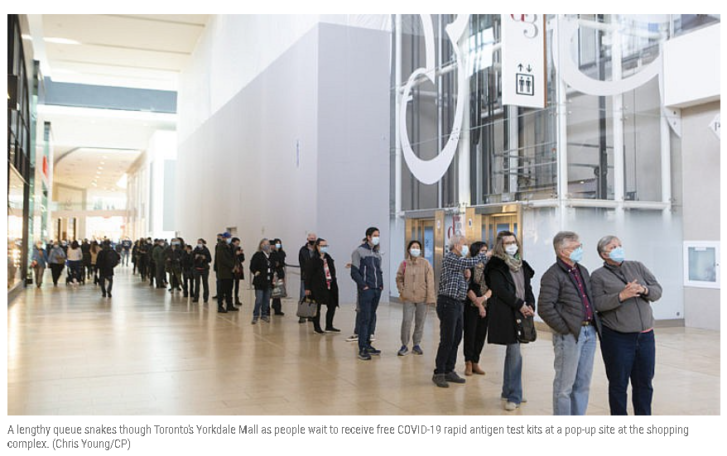

The province says that “throughout December to mid-January, two million rapid tests will be provided free of charge at pop-up testing sites in high-traffic settings such as malls, retail settings, holiday markets, public libraries and transit hubs.” Given each pack contains five tests, that means just 400,000 packs for a population of 14.7 million, or one chance in 30 of scoring a free pack. (Maclean’s has asked Ontario’s Health Ministry to double check the number of tests and packs being given away.)

The government touts how many tests have been distributed to workplaces—qualifying businesses get umpteen boxes of free rapid tests for their workers—and to students, who get five tests to use over the holidays. But if you don’t work for one of those businesses, or don’t have school-aged children, then the only way to get tests is to line up, or buy them through the private market, paying anywhere from $10 to $40 a test, if they are able to find them. Bear in mind these tests should be done every few days, or immediately before each gathering, to identify someone while they are infectious. At those prices, the costs are beyond the budgets of many Canadian families, and a tangible example of the deep inequities exposed by this pandemic.

On Wednesday, as word spread on social media that free rapid tests were being handed out in Ontario, a Hunger Games race began: people rushed to the handful of locales, only to find they’d run out hours before. The next day, long lines formed early at the few pick-up locations, which quickly exhausted their supplies. Currently, there are few locations outside the Greater Toronto Area, prompting more frustration.

The temporary holiday measures just unveiled in Ontario are miserly compared to Nova Scotia’s rapid testing strategy, now more than a year old. It has numerous testing sites (run by volunteers who have been trained by health-care professionals) and a new giveaway plan that saw 400,000 tests handed out in one day for a population of fewer than one million people. Some version of “Why can’t we do that?!?” is the most common reaction that Dr. Kevin Wilson, an epidemiologist in Halifax, hears from people outside of Nova Scotia about his province’s program. Roughly once a week, he drops into one of those sites to get a test before going to the gym or a big gathering.

Making rapid testing both routine and normal is a key aspect to the Nova Scotia program. “If people want to keep things open, the only way to safely do that with a virus that spreads without symptoms is to do regular testing. Full stop,” said Dr. Lisa Barrett, the infectious diseases researcher at Dalhousie University in Halifax, who helped start Canada’s first rapid testing pop-up sites in late November 2020. “[It’s] not to make cases low [that] you get tested, but to keep cases low,” Barrett explains.

The delays and difficulties surrounding the rollout of rapid tests in Ontario feels emblematic of the frustrations endured by many across this country during this pandemic. We’ve struggled to get PCR tests. We were so confused by government vaccine appointment systems that a group of volunteers started Vaccine Hunters Canada to help us. Then there is the cruelty endured by parents and their school-aged kids as they were repeatedly thrown into what colleague Shannon Proudfoot called the “dystopian hell” of online learning. What made the latter so utterly exasperating is that rapid testing could have prevented some school closures by identifying and isolating infectious students before they passed COVID-19 to their schoolmates.

Indeed, the benefits of rapid testing in keeping community spread low have been clear for a long time. In the autumn of 2020, virtually the entire nation of Slovakia was tested two to three times in quick succession with rapid tests. Some 50,000 tests coming back positive, meaning a positivity rate of around four per cent. A week after the tests were done, case loads dropped by 60 per cent. In Europe, rapid tests are either free or ridiculously cheap, costing a dollar or two per test.

Except for Nova Scotia, provincial governments decided not to adopt the European model and incorporate rapid tests within their public health measures for the general population. As a result, even though provinces pressed Ottawa to buy and send them tens of millions of rapid tests, they left most of them on shelves for much of 2021. So great was the number of unused tests that, in a classic example of federal-provincial passive aggressiveness, Ottawa created a webpage detailing how many tests had been sent to each province, how many had been distributed and how many used. As of Dec. 15, Canada has received 99 million tests, of which 67 million have been deployed but just 15.5 million have been reported as used. In Ontario, fewer than one third of its tests have been used, according to the federal data.

On Feb. 24, 2021, I wrote again about experts pressing for widespread rapid testing in Canada. “We are speaking of an infectious disease,” explained Dr. David Juncker, a biomedical engineering professor at McGill University in Montreal. “Yet our testing is all about detecting infected people, as opposed to detecting infectious people.” The advantage of rapid testing is that they can “be more efficient at stopping the pandemic” by identifying asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic people early, while they are infectious.

That’s even more true now, as Delta is being pushed aside by the far more infectious Omicron as the dominant variant in Canada. The value of repeated testing can be seen in professional sports. For instance, though pretty much 100 per cent of the National Hockey League’s players are fully vaxxed, the league has already put at least 17 per cent of its players in its “COVID-19 protocol” this season thanks to its extensive testing program— something unavailable to most Canadians. (Even so, right now, the Calgary Flames has only five players eligible to play on its active roster.)

For much of December, it has felt like we are back at the end of 2020, and again, the Ontario government was a step or two behind the virus.. Case counts are rising quickly, this time because of Omicron, and Dr. Steini Brown of the Science Table warns “this will likely be the hardest wave of the pandemic.” Once again, it’s hard to get a PCR test in hard-hit areas. COVID-19 is once more sweeping through schools so quickly that boards are telling students to bring all their belongings home for the holidays, just in case.

And even though experts warned for months that the protection from just two doses of vaccine was waning; even though Health Canada authorized the use of Pfizer and Moderna boosters in early November, Ontario has given third doses of vaccine to fewer than 10 per cent of its population and is only now trying to ramp up its efforts. Last year, it delayed enacting public health restrictions until Boxing Day. This year, it only started distributing free rapid tests to the general population 10 days before Christmas.

Will Ontario continue to hand out free tests after the holidays? It depends how this rollout proceeds. The Ford government is sensitive to negative publicity, especially as there is an election coming in 2022, and images of lines of people queuing outside pop-up sites or provincially-run liquor stores may not be the happy holiday images they imagined.

On the flip side, if people take to social media to talk about how rapid testing contributed to them getting through the holidays at a time of explosive case growth, then #FreeTheRATs may have proved its worth, and rapid tests for all will be made permanent.

Article From: Maclean’s

Author: Patricia Treble