Early data suggests strong protection against delta, no evidence for boosters in the general population yet

New Canadian data suggests the bold strategy to delay and mix second doses of COVID-19 vaccines led to strong protection from infection, hospitalization and death — even against the highly contagious delta variant — that could provide lessons for the world.

Preliminary data from researchers at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) and the Quebec National Institute of Public Health (INSPQ) shows the decision to vaccinate more Canadians sooner by delaying second shots by up to four months saved lives.

The researchers excluded long-term care residents from the data, who are generally at increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19, in order to get a better sense of vaccine effectiveness in the general population — and the results were exceptional.

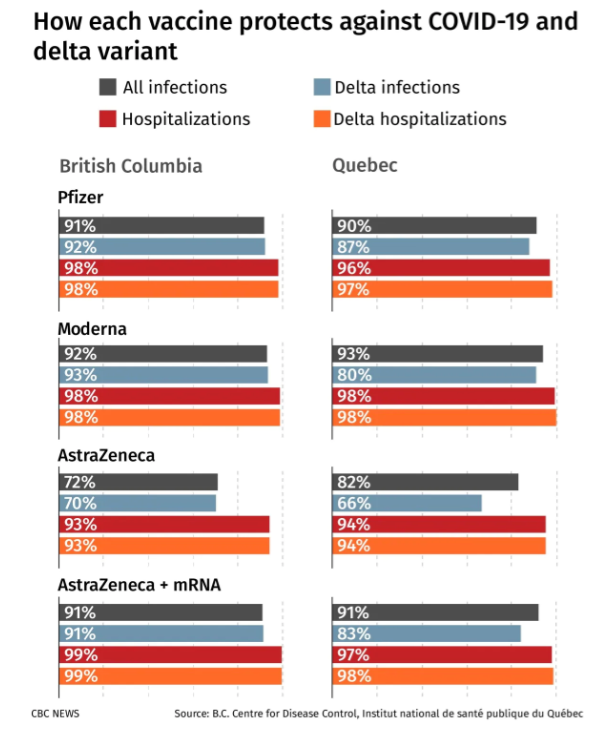

The analysis of close to 250,000 people in B.C. from May 30 to Sept. 11 found two doses of any of the three available COVID-19 vaccines in Canada were close to 95 per cent effective against hospitalization — regardless of the approved vaccination combination.

That means for every 100 unvaccinated people severely ill in Canadian hospitals, 95 of them could have been prevented by receiving two doses of either the AstraZeneca-Oxford, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, or some combination of the three.

Dr. Danuta Skowronski, a vaccine effectiveness expert and epidemiology lead at the BCCDC whose research laid the groundwork for the decision to hold back second doses based on the “fundamental principles of vaccinology,” says the early data is extremely encouraging.

“We were very pleased to see during the period when the delta variant was not just circulating, but predominating, that we had such high protection nonetheless against both infection and hospitalization,” the lead researcher on the analysis told CBC News.

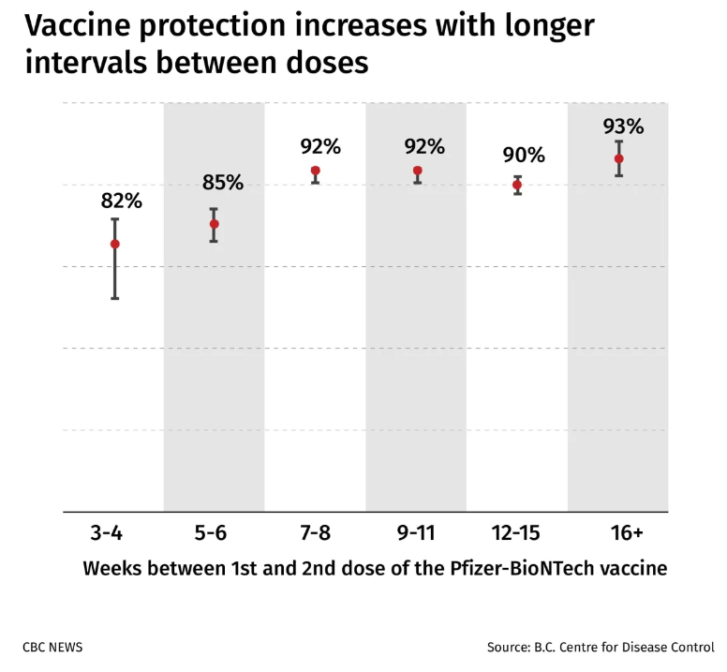

“Protection was even stronger when the interval between the first and the second doses was more than six weeks apart.”

In fact, the research showed that protection against COVID-19 infection from two doses of the Pfizer vaccine rose dramatically when the first and second shots were spread out — from 82 per cent after three or four weeks, to 93 per cent after four months.

“For those who received the AstraZeneca vaccine as their first dose, their protection against any infection was lower than for mRNA vaccine recipients, but they had comparable protection against hospitalization and that’s the main goal,” she said.

“But for those who received a first dose of AstraZeneca and a second dose as an mRNA vaccine, their protection was as good as those who had received two mRNA vaccines. So that’s also a really important finding from this analysis.”

While the work is still being finalized and has not yet been submitted as a pre-print or undergone peer review, the researchers felt it’s important to get their early data out now to inform the public and policymakers here and abroad about the positive results.

“The mix-and-match schedules are protecting well, and my preference would be that those countries who don’t recognize that get to see our data as soon as possible,” she said, adding that the findings were sent to U.S. officials for review of international travel policies.

“My hope is that when they see the evidence that they will change those policies, which are frankly inconsistent with the science.”

Quebec data backs up findings from B.C.

In Quebec, thousands of kilometres away and with a different population, demographic makeup and early vaccine rollout approach — the results of a twin study that will be published alongside the B.C. data were astonishingly similar.

Of the 181 people who died from COVID-19 from May 30 to Sept. 11 in Quebec, just three were fully vaccinated. Researchers say that corresponds to a vaccine effectiveness against death upwards of 97 per cent based on a population analysis of nearly 1.3 million people.

Similar to the B.C. data, the Quebec research also showed more than 92 per cent protection from hospitalizations — with Pfizer, Moderna or AstraZeneca vaccines — against all circulating coronavirus variants of concern in Canada at that time, including delta.

“The takeaway is whatever vaccine people had, if they got two doses they should consider that they are very well protected against severe COVID-19,” said Dr. Gaston De Serres, an epidemiologist at the INSPQ. “That’s the main message.”

The analysis found Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were 90 per cent effective at preventing COVID-19 infections — either asymptomatic, symptomatic, or those needing hospital care — a protection rate equal to those with an AstraZeneca and mRNA vaccine combination.

For people who received two doses of AstraZeneca, the research suggests a slightly lower level of protection from infection — but one that is still remarkably high at 82 per cent.

De Serres says the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) and the Quebec Immunization Committee (CIQ) are looking at whether additional doses may be needed for that group, but says it’s “not as pressing” given the strong protection from hospitalization.

“For the time being, just stay put. If there is a recommendation for you to get an additional RNA dose you’ll know in time,” De Serres said. “But feel that what you’ve got is still a very good regimen to protect you against what we fear most — which is severe COVID-19.”

The NACI recommendation in March to delay second doses of all three COVID-19 vaccines by up to four months was not without controversy at the time, and no doubt led to confusion among many Canadians about whether they were adequately protected.

Canada’s Chief Science Adviser Mona Nemer said in early March that the strategy amounted to a “population level experiment,” while at the same time health officials tried to reassure the public that the approach was safe and effective.

Deepta Bhattacharya, an immunologist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the study, says the results are “very encouraging” and provide evidence of “improved real world protection” from delaying second doses.

But he admits even he was initially skeptical.

“I was uneasy about it in large part because I just wasn’t sure how well the protection would hold up in the interim,” he said. “Obviously it turned out well … but it was risky, and that gamble paid off.”

Bhattacharya says the Canadian data now provides real world evidence that vaccinated people produce more antibodies if their second shot is delayed, and the quality of those antibodies may actually improve — which could explain the better protection against delta.

“What I’m really wondering now going forward is whether the recommendations are going to fundamentally change as to when we should get that second shot,” he said, referring to other countries around the world. “I wish I’d gotten mine later now in retrospect.”

Keeping ‘eye on the prize’ means avoiding hospitalization

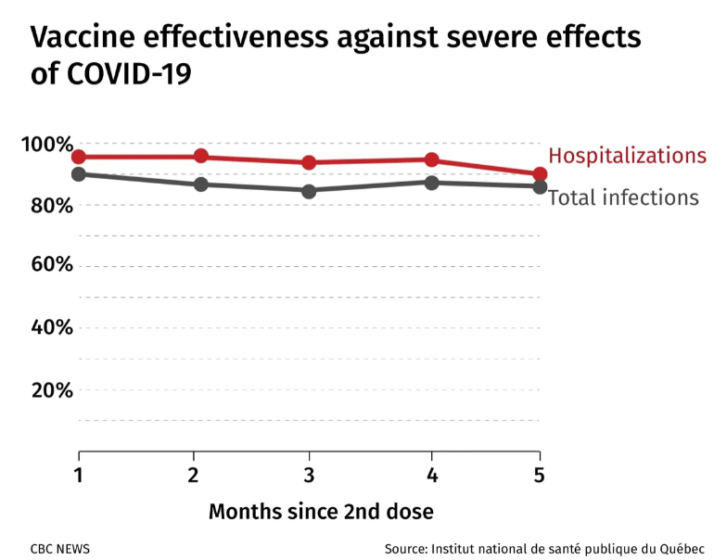

The data also has implications on whether average Canadians need booster shots, particularly given that emerging real world data in other countries like the U.S., Israel and Qatar show evidence of waning immunity that has prompted the rollout of third doses.

But experts caution that while countries reporting diminished vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 infection may be making headlines, the more important factor is that the studies largely show the vaccines have prolonged protection against severe COVID-19 — meaning hospitalization and death.

“We really should keep our eyes on the prize, which is preserving healthcare system capacity and preventing unnecessary suffering,” said Skowronski. “We’re not going to prevent every case of COVID-19. Our goal was never to prevent the sniffles. Our goal was to prevent serious outcomes.”

Still, the B.C. and Quebec data showed “no signs” of waning immunity in the general population four months after the second mRNA dose and strong protection against infection of more than 80 to 90 per cent maintained. The analysis doesn’t go beyond five months, but the researchers will continue monitoring vaccine effectiveness.

“We should be reassured that our vaccine effectiveness from this calculation, from what I’ve seen, will be robust with its protection,” said Alyson Kelvin, an assistant professor at Dalhousie University and virologist at the Canadian Center for Vaccinology and the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization in Saskatoon who was not involved in the research.

“We must continue to have public health measures in place as well as expect at some point we might need a booster, but data like this will inform when we do and right now it’s suggesting that we don’t need it yet — but we have to keep vigilant.”

Skowronski says that while she supports giving long-term care residents and immunocompromised people third doses of COVID-19 vaccines to increase their protection based on emerging data, including from Canada, there isn’t enough evidence yet for average Canadians.

Until then, she says Canadians should feel well protected against severe outcomes from COVID-19 in the delta-driven fourth wave if they’re fully vaccinated with any of the approved vaccine combinations in Canada.

“We’re going to have to learn to live with SARS-CoV-2, including in its very many future iterations,” she said.

“But so long as we can prevent severe outcomes and maintain healthcare system capacity, we can come to a kind of a mutual understanding with this virus.”

Article From: CBC news

Author: Adam Miller