A. Gavin Clark is a retired microbiologist from the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine.

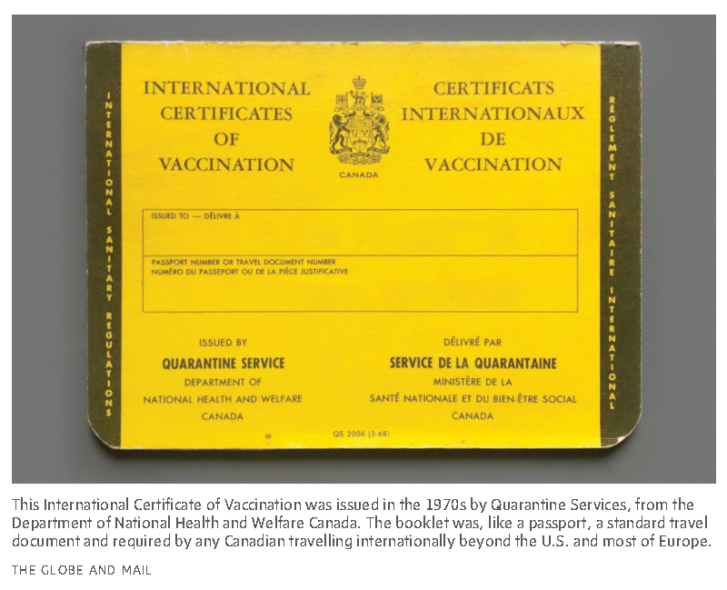

When I was travelling in Asia in the 1970s, I had to carry a little yellow booklet called the International Certificate of Vaccination (ICV). It was issued by Quarantine Services, from the Department of National Health and Welfare Canada. It contained only 10 pages of text, but each page was recognized around the world, and had detailed columns collecting dates, signatures of vaccinators, vaccine origins, code numbers and approved stamps. This meant that a personal record existed of what, when, where and with which agent a person was vaccinated. Without the required vaccinations, I was not allowed to enter specific countries.

Today, as governments around the world have realized that infections, be they epidemic or pandemic in their spread, have an economic and political cost, personal records of vaccinations and tests against COVID-19 are increasingly being required by countries to allow travel. Most countries are considering proof of vaccinations at their borders.

And each of the pages in that ICV tells a story about the history of vaccines, the history of how those viruses have been constrained or overcome, and what we need to remember going ahead.

The first two pages of my booklet were for vaccination – and revaccination as needed – against smallpox, which devastated, among others, indigenous populations in the Americas. This served as a reminder that no vaccination is totally lifelong, and that some require booster reinoculations. Smallpox is a uniquely human disease with no other animal host, meaning that it could be “extinguished,” and indeed, the WHO declared the world smallpox-free in 1980. But everyone born after that date is therefore immunologically naïve – which is to say, defenseless – to smallpox, if it were ever to reoccur.

That fear re-emerged as recently as 2017, when a Canadian lab was able to synthesize the related horsepox virus (which is not known to harm humans, and is also believed to not exist in nature any longer) using off-the-shelf units of DNA, causing international concern that this could lead to a bad actor reproducing smallpox.

Pages four to seven of my yellow booklet were devoted to Cholera. The number of pages shows the terrible impact that cholera had on the world. Originally called “Asiatic Cholera” because of its origin, cholera became a European and then a worldwide problem when it was carried by immigrants, traders, armies and seafarers. From 1822, Canada suffered through multiple waves of cholera, which caused Canada to designate Quebec’s Grosse Isle as a quarantine station. Hundreds of immigrants got no further, dying on the island.

Untreated, cholera has a high death rate because the bacterium that causes it, Vibrio cholerae, produces a toxin when in the gut. This toxin causes a loss of fluids and salts from the body. This can prompt up to 20 litres of uncontrolled diarrhea to erupt from the infected body every day, which leads to loss of electrolytes, shock and death.

Prior to the 1970s, a phenol-inactivated, injectable vaccine gave a partial protection; that’s what I received. Today, the vaccine is oral, directing the preventative straight to the site of potential infection. However, the greatest medical success has come from the design of supportive therapy using oral rehydration salts (ORS). A salt pack mixed into boiled water can be administered anywhere without medical involvement. It is cheap and highly effective, and is a major reason for the drop in cholera deaths.

Cholera remains endemic in Bangladesh and parts of sub-equatorial Africa, but it is a constant fear wherever sanitation breaks down, owing to war, natural disaster and insurrection. For instance, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti resulted in 820,000 cases of cholera and 10,000 deaths. Haiti never had cholera outbreaks before, but a scientific review concluded that it was introduced by sick Nepalese UN peacekeepers – a tragic irony.

Sadly, even though cholera is a purely human disease, it is unlikely that it can be totally eliminated. Cholera is seasonal in places where it is endemic; in the “off-season,” the bacteria becomes attached to aquatic zooplankton and the egg cases of copepod crustaceans where it goes into a state of hibernation, and is unculturable in the laboratory. Notably, there were seven cases of cholera in British Columbia in 2018 attributed to eating herring eggs. No country currently requires cholera vaccination for entry, but travel advisories do exist for certain countries.

Pages eight and nine of the ICV were for yellow fever. This viral disease is mostly seen in monkeys and lemurs, but it can also be transmitted to humans, and then person-to-person, by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti). The virus is endemic in tropical Africa, Central and South America wherever the virus and such mosquitoes exist. There is no specific anti-viral drug and the resulting hepatitis can be fatal, but there is an excellent available vaccine.

Pages 10 and 11 of my ICV were for “Other Vaccinations.” My booklet listed, on those pages, TAB(T), polio (Salk) and Trivalent oral polio. TAB, with or without the T (for tetanus), is a universal vaccine that covers typhoid fever and para-typhoid A or B. Tetanus toxoid vaccine is an effective vaccine, and a fairly common one; most patients with deep wounds requiring stitching or surgery will receive a tetanus shot.

The “Polio” entry is another matter. Poliomyelitis is a viral disease that was once dreaded for its paralytic potential. Before the 1950s, children with leg braces or being kept alive inside iron-lung ventilators were not rare. People may have forgotten that the March of Dimes, a non-profit that today focusses on the health of mothers and infants, was founded to raise money for polio research. Canada played a major role in that regard: Toronto’s Connaught Laboratories were vital to the research for and production of the first polio vaccine.

Wild polio virus exists in 3 types: WT1, WT2, WT3 (which is why I received a three-part vaccination). All were present in Canada in the 1950s, especially among the Inuit, but after vaccination campaigns, North America was declared polio-free in 1979 by the WHO; WT2 and WT3 were declared extinguished worldwide in 1999 and 2012, respectively. Today, WT1 is found in Bangladesh and Afghanistan. The WHO-directed vaccination programs have been remarkably successful. It is now possible to count the cases of WT1 polio worldwide on the fingers of two hands. Compare this with 1953, when Canada counted 9,000 cases of poliomyelitis and 500 deaths.

My booklet only lists the classically problematic infectious diseases with epidemic potential at that time. But the world has changed. While AIDS, SARS, and the norovirus have made the news, the massive number of “new to medicine” bacteria and viruses that have been detected since 1970 dwarf those mere three. Some “new” viruses with marked lethality have, however, been contained within their endemic locales by WHO directed public health measures. For example, Nipah virus in India has a death rate of up to 75 per cent, while Ebola (25 per cent to 90 per cent) and Lassa fever (23 per cent) have been restricted to Africa.

The dangers posed by refugees from unstable countries, their congregation in migrant camps and travel itself all offer chances for the spread of endemic diseases to become epidemics in immunologically naïve countries.

Two-thirds of all viruses that infect humans are zoonotic – that is, they live, grow and multiply in and among birds and non-human animals. The size of the pool of undetected viruses is unknown. But to give a sense of the sheer scale of the situation, the last three coronavirus epidemics – SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 – have been linked to bats, which are the most numerous mammals on earth, with more than 1,500 species with individual food sources and habitats. These bats appear to carry many coronaviruses, and have not only the unexplained ability to resist infection, but also to adjust this resistance as the virus mutates.

Bats do have an important function in controlling insects, which are also significant vectors of disease. But deforestation drives bats to urban areas, where their feces and urine can spread virus. It is not illogical to say that we have not seen the last of bat-related coronavirus pandemics.

As for the future of COVID-19, there are two possibilities: The virus becomes endemic, with seasonal or sporadic re-emergences – after all, seasonal coronaviruses have long been one of the causes of the common cold – or the range of new vaccines will be able to suppress it as well as other vaccines have limited childhood infections. Either way, we will need something like the ICV to keep track.

I know that since 1970, I have had a number of other vaccinations administered by a family doctor (now retired, with files deposited somewhere), at walk-in clinics, hospital group practices and pharmacies. Where are the documents, the historical trail? Certainly not in one place, or even in my own hands. Canadians of European origin will remember the reams of paperwork needed to travel in Europe between and after the two World Wars. Even today, the documentation required in order to enter Russia feels like undertaking a genealogical quest, and despite the “union” part of the European Union, the countries are far from unified in their approach to travel and entry requirements.

As coronavirus variants continue to spread, and as countries institute or consider introducing policies to demand proof of vaccination from travellers, it is time for Canada to act as well. The federal government should once again mandate the equivalent of the travel booklet issued by the Department of Health and Welfare Canada for everyone – whether they’re intending to travel or not. It will show responsible public-health leadership – and remind us of the stories we need to remember as we move ahead into a future we cannot hope to predict.

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: A. GAVIN CLARK