Vaccinating at least 90 per cent of eligible Canadians against COVID-19 could tip the balance against new, more infectious variants much better than the 75-per-cent uptake Ottawa is pushing for. Here’s how things could play out

The difference between a fall in which COVID-19 is in retreat and one where it surges back in a fourth deadly wave may come down to whether Canada can achieve a B or an A+ with its vaccination effort.

That is the upshot of a new analysis conducted for The Globe and Mail that demonstrates the value of vaccinating at least 90 per cent of eligible individuals, including children 12 and up, as soon as possible. In Canada, this would be equivalent to the current rate of vaccination against polio as well as measles, mumps and rubella.

On Friday, Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam pointed to the federal government’s latest epidemiological models that show a vaccination rate of 75 per cent is a key goalpost that can allow the most restrictive public-heath measures to be lifted for the summer – though people should continue with precautions such as masking and social distancing when gathering with non-household members. Once the 75-per-cent threshold is reached for second doses, Dr. Tam added, “it may also be safe to begin easing personal protective measures without overwhelming hospital capacity.”

While the message is an important one, for some experts it overlooks the immense value to Canada of setting a higher vaccination target. Current numbers show that a 75-per-cent vaccination rate is achievable, indeed it has already been achieved for those over 60. Yet modelling suggests that if Canada’s vaccination rate can reach 90 per cent, the result will not simply be a better outcome, it could be a different path entirely – one that substantially reduces of the risk of a fourth wave.

These alternative futures are a by-product of the variants of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 and their influence on the spread of the disease in Canada. At least some of the variants are more transmissible, which means that each case of COVID-19 will, on average, spark a higher number of subsequent infections.

When the pandemic began, epidemiologists estimated that about two-thirds of the population would have to be resistant to the virus to reach herd immunity – a state in which new outbreaks die out because the virus can’t spread to enough susceptible people. A higher disease transmission means that more people must be vaccinated to reach that goal. That is why current estimates for how many vaccinations will be needed to eliminate COVID-19 have shifted upward and why some scientists have suggested that herd immunity may now be out of reach.

But even if this proves true, Canadians have good reason to push hard to achieve a vaccination rate well above 75 per cent, said Caroline Colijn, a mathematician who specializes in infectious disease at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C., and who contributed to the federal modelling. “We can get practical herd immunity,” Dr. Colijn said. “That doesn’t mean we never see COVID-19 again. It doesn’t mean it never comes across our borders. But it does mean we can reopen, supported by vaccination.”

To illustrate the point, Dr. Colijn worked with The Globe to develop a model that shows the difference between vaccination rates of 75 and 90 per cent under different scenarios, including the case where a variant of the coronavirus threatens to revive the pandemic. This could be because of a new variant that emerges on its own or a genetic combination of existing variants – such as one that was recently reported in Vietnam. Either would have the potential to improve COVID-19′s ability to overcome the challenge posed by vaccines.

In all scenarios, a higher vaccination rate leads to a significantly better outcome, both in terms of total infections and hospital admissions. Often, it is the difference between a sizable fourth wave and no wave at all.

In the four scenarios below, the model used is based on one developed by Dr. Colijn and her colleagues that was published in the journal Science earlier this year. It uses age and essential worker contact rate information from demographic data, and captures what is know about disease susceptibility, severity and vaccination patterns. The results reflect total infections, including asymptomatic or unseen cases of COIVID-19. Reported cases, hospital stays and deaths will each have their own curves, but they will rise and fall in lockstep with the infection rates shown.

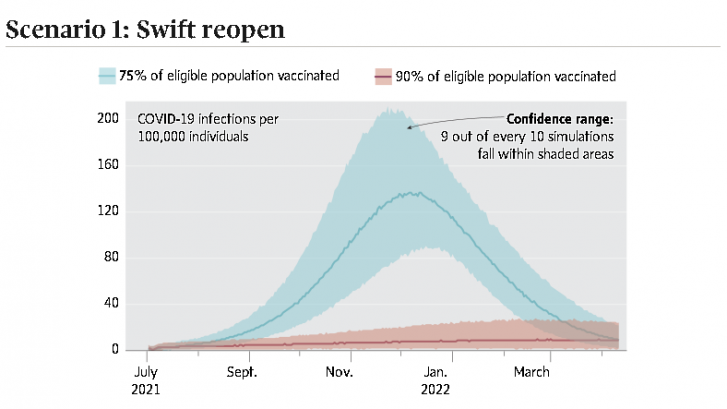

In the first scenario, rapidly dropping case counts and increased vaccine availability prompt provincial governments to drop most public-health measures at the beginning of summer, around June 24. For the next two months, infections remain at a relatively low level, as they were during the summer of 2020. But as infectious-disease experts are quick to point out, this is no longer the same pandemic we saw last year.

As restrictions are lifted, variants of the virus that begin emerging in Canada over the winter and spring will be able to hit a population where individuals are no longer in isolation for the first time. One of the key limitations of the model is that at this point no one knows the precise transmissibility of the current mix of virus variants in a reopened society. A reproduction number of less than one is needed to prevent the pandemic from rebounding. In this scenario, that number is set at 3.

Because vaccines do not guarantee total protection, a vaccination rate of only 75 per cent means that significantly more than one quarter of the population remains vulnerable to COVID-19. In the absence of continued social distancing and masking, that eventually allows infections to build up to a fourth wave during the fall. Under identical conditions, a vaccination rate of 90 per cent suppresses the surge.

The two curves illustrate how tightly interwoven Canada’s vaccination rate is with the continued need for public-health measures. The risk is that people may equate a rate of 75 per cent, which the federal government has identified as desirable, as signalling the end of the pandemic. Instead, it merely allows a less limited set of restrictions.

“Communities with lower vaccination rates will be particularly at risk as we reopen, because it’s there that the spark of an introduced case can cause an outbreak,” Dr. Colijn said.

On the other hand, higher rates of vaccination everywhere will leave the virus nowhere to hide, allowing for a safer reopening. This would mean shaving away at the remaining fraction of the unvaccinated, including children 12 and over and those who are hesitant but open to persuasion. Then, the risk of a fourth wave could be curtailed.

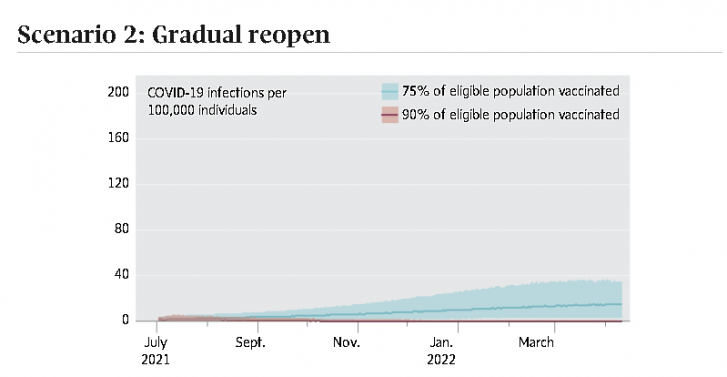

As Dr. Tam made clear on Friday, if strong public-health measures continue alongside the vaccination effort, then infections are more effectively contained. This scenario is the one that most closely resembles what Ottawa has in mind. Here, a more gradual lifting of restrictions on gatherings and other measures reduces the reproduction number to 2.5.

The measures provide enough of a barrier to ensure that the next wave is a modest one when the vaccination rate is 75 per cent. However, everyday life is not yet “back to normal,” which may put pressure on provincial governments to ease up on measures faster than they should. There is less need to worry about this if the vaccination rate hits 90 per cent because it flattens the infection curve entirely. Jason Kindrachuk, a virologist at the University of Manitoba, sums up the tension between what is acceptable and what is excellent:

“We want to have targets that we think are going to be effective … but our best kind of outcome is that we exceed those targets,” he said. “Ultimately having more protection is not going to be a bad thing.”

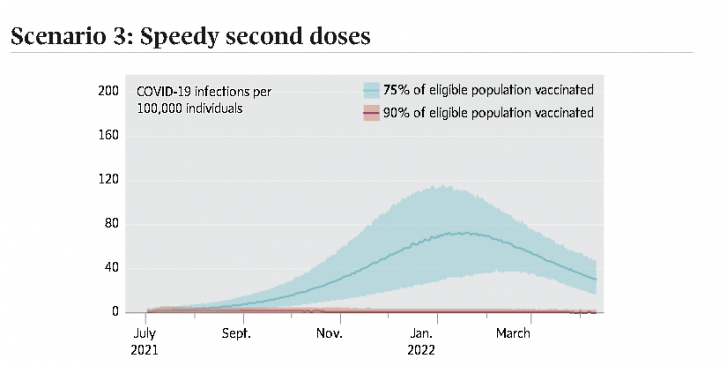

Another variation on the theme is evident if vaccine supply continues to rise and second doses are made available more quickly than the four-month interval Canadians have expected up until now.

In this scenario, half of all those who are vaccinated have already received their second dose. This raises vaccine efficacy and makes it harder for the disease to spread among those who are fully immunized. Even in this optimistic scenario, a 75-per-cent vaccination rate is insufficient to completely block a fourth wave without additional public-health measures, but it is more muted.

With 90 per cent of eligible Canadians vaccinated, the pandemic is controlled with the added benefit that fewer cases means fewer opportunities for variants to arise in individuals who are only partially immune. While there remains uncertainty about vaccine efficacy in relation to the combination of variants present in Canada today, it is highly likely that a higher vaccination rate will still provide a better outcome.

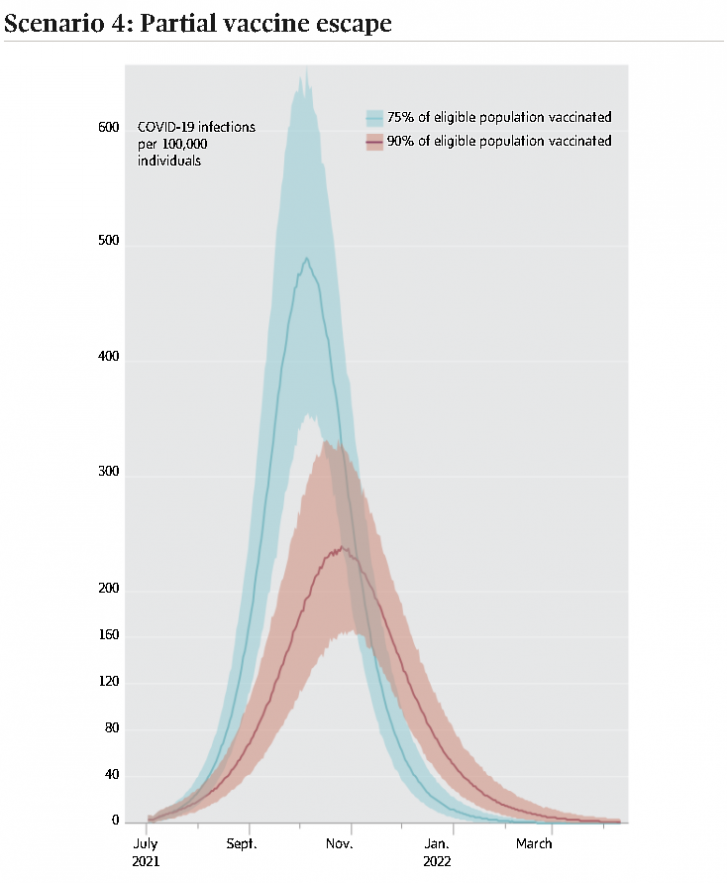

For public-health officials, the worst-case scenario is the emergence of a new variant of the coronavirus that vaccines can’t stop. This is known as “vaccine escape” and its likelihood grows somewhat as the noose tightens on the pandemic and conditions favour the emergence of new variants.

In this model, a complete vaccine escape would be off the charts and force us back to a new round of lockdowns. This scenario shows only a partial vaccine escape. Here, a variant takes hold that vaccines are less able to manage. Infections and hospital admissions rise steeply in the absence of social distancing. But while a fourth wave is inevitable in this scenario, its impact is lessened by the higher vaccination rate.

The difference shown here could be magnified still further if the escape variant is more transmissible, which increases the risk of infection among people who have not received a shot, including children under 12.

“If it’s more transmissible, then it’s going to sweep through the population and it’s going to find all the pockets of people that are not vaccinated,” said Jeff Joy, a research scientist specializing in the evolutionary genetics of viruses at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS.

In this scenario, a partial escape means that vaccines are less able to arrest transmission as well as illness, and vaccinated individuals can serve as a bridge, allowing the virus to more easily find those who will not or cannot be vaccinated. Dr. Joy added that it is the prospect of this scenario that explains why, even at a 90-per-cent vaccination rate, one measure Canada cannot afford to drop is continuing genomic surveillance of COVID-19.

“That’s really important,” he said. “Once we suppress cases down to a really low level, it then becomes feasible to use genomic surveillance to track the hot spots. … Then we can focus our public-health resources into the areas where they’re going to do the most good at preventing widespread transmission.”

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: IVAN SEMENIUK