DOSE OF DESPERATION

If there was a global race for COVID-19 vaccine, wealthy nations won it, and countries like Angola lost. The rollout left Canada awash in doses. In Africa, meanwhile, every drop is precious.

Alex Boyd Toronto Star

LUANDA, ANGOLA The sun is high in the sky as the plane’s wheels make gentle contact with the runway, an expanse of faded tarmac that gives way to red earth in the distance.

A crowd has assembled, but they’re not here to greet the tired-looking human arrivals descending the stairs to the runway.

Airport workers swing open the cargo hold of the white-and-gold Emirates jet to reveal crates protecting what has become the most sought-after liquid on Earth — COVID-19 vaccine.

This particular batch landing in Angola, almost half a million doses of AstraZeneca, has been mostly paid for by Canada, as part of its pledge to help vaccinate the world.

In Canada, three out of four people on the street are already fully vaccinated. The frenzy for shots cooled months ago, with some clinics now resorting to throwing extra shots away. But here in Angola, a nation on the western coast of Africa, this sole shipment of vaccine is met by a delegation that would normally befit a visiting dignitary. Photographers snap pictures as the health minister strides onto the tarmac.

The doses are here to feed a hungry distribution system in a country at a time when just five per cent of people are fully vaccinated.

Speaking to a halo of microphones as engines rumble nearby, Dr. Silvia Lutucuta tells the crowd of media that the new doses will reinforce Angola’s national vaccination plan, and tries to reassure that everyone who’s already had a first dose will get a second.

“Starting tomorrow, we will have this AstraZeneca vaccine at the vaccination centres,” she says in Portugese, the national language held over from the colonial era.

For the world’s poorest countries, COVID hit like a hurricane, smashing fragile health-care systems and snatching back hard-earned gains in anti-poverty and education.

In Angola, a sprawling tropical country with vast oil reserves and a buzzing capital city perched on the edge of the Atlantic, the virus blindsided a reform-minded government already struggling with dropping oil prices, not to mention the nation’s ongoing recovery from decades of war.

And while no one on the tarmac this day knows it yet, more dark clouds are gathering. Within weeks, a new variant will be discovered in nearby Botswana, and will begin spreading like wildfire.

Angola will be one of the first nations in the world to face travel bans after cases of Omicron are detected in southern Africa — while also enacting a few of its own — and, not long after, case counts will spike higher than ever before.

Wrapped in tarps, the crates of tiny glass vaccine vials of vaccine are sprayed with disinfectant. Officials peel the backs off of plate-sized stickers emblazoned in big, block letters spelling CANADA and slap them on the sides of the crates.

Within minutes of its arrival, the vaccine is lifted onto cargo trucks and sent on its way. The first doses are meant to go into arms in the morning and, in Angola, there’s no time to waste.

Imagine the world is a house. Right now, it’s a house on fire.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, health experts have argued vaccines would be one of the most likely ways to stop it in its tracks.

It usually takes years to develop just one, but the global community poured enough collective time and money into the vaccine race that the world ended up with several, an embarrassment of riches that most did not see coming.

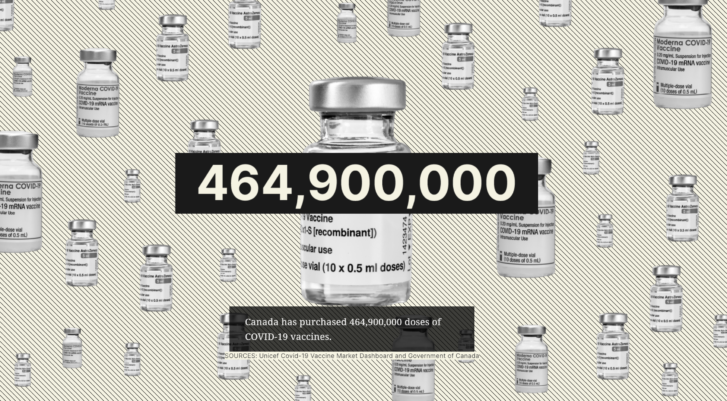

Despite pleas from the global health community to work together, countries that could afford to — such as Canada — snapped up the majority of the first shipments of vaccines before they’d even been shown to work, betting on candidate doses like horses and pouring money into those most likely to cross the finish line first. With little ability to make vaccines itself, Canada inked agreements for seven different shots before the first was even out of trials.

The supply turned on like a faucet in late 2020 — the first vaccine authorized in the West was the Pfizer-BioNTech version, though Moderna and AstraZeneca weren’t far behind — first a trickle and then a flood.

Instead of dousing the flames throughout the whole house, though, the approach to COVID-19 has seen much of the flow diverted to particular rooms, if you will, dividing the globe between the vaccinated and the unprotected.

There’s one fact that tends to come up when talking to campaigners for vaccine access about Canada and COVID vaccines.

It is this: Canada has purchased more doses per capita than any other country on the planet. If the government takes advantage of its seven agreements — and in fairness, not all those vaccines have been authorized yet — it would have enough vaccine to give everyone in the country almost six shots.

But Canada isn’t alone.

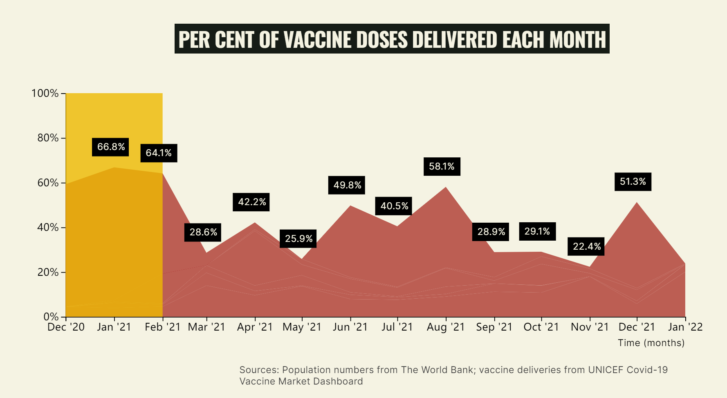

In the first three months that vaccines were available, two thirds of the global supply went to a small number of higher income countries — including the U.K., the U.S., the European Union, Russia and China — with only a third of the world’s population.

Roughly a third of the world has yet to see a single shot.

For the poor countries left out, the inability to access vaccines is not just a health issue, but an existential one. The World Bank has warned that the virus hit poorer countries hardest. Rates of extreme poverty worldwide had been in decline for two decades until the virus arrived, threatening to upend years of progress.

In Africa, less than 10 per cent of the population had two doses by the end of 2021 — and the resulting health crises and shutdowns have pushed millions to the brink.

Rwanda, which has worked mightily to move on from genocide, is experiencing its first recession, with an additional five per cent of the population now living in poverty.

In Uganda, where schools have been shut down for a staggering 80 weeks, almost a third of students are expected not to return because of an uptick in child marriages, teen pregnancies and child labour.

And in Angola, aid workers who spent months in lockdown in the city eventually returned to rural areas and were stunned by the sight of so many malnourished children.

Now they face the wave of Omicron largely unvaccinated.

One of South Africa’s most high-profile vaccine experts is Dr. Shabir Madhi, based at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, who has spent a career working to develop childhood vaccines and make them more accessible. This isn’t the first time he’s seen a vaccine finally unloaded in Africa long after its use was commonplace in North America. Still, to watch doses roll out to wealthy nations while the death toll continued to rise elsewhere, has been hard.

In the face of Omicron, the current crop of vaccines has proven to be good at preventing serious illness, but not infection. As a result, they were “pretty much wasted in children,” he argues, given their relatively low risk for serious illness. While that point is likely to be debated by some, what’s undeniable is that high-risk individuals in poor countries have died by the millions.

Notably, as of November — 18 months into the pandemic — three out of four health workers in Africa remained unvaccinated.

“It hardly comes as a surprise that high-income countries didn’t play the ballgame in terms of putting some sort of action behind their words of vaccine equity,” he says. “But the consequences of that is they’ve ended up protecting children against infections at a cost of life in low income countries.”

After leaving the airport, the cube vans carrying vaccine plunge onto the chaotic roadways that knit Luanda’s urban centre together, becoming a couple of white blips in the speeding, honking, swerving late afternoon traffic.

The noise drops away as they pass through a high gate into a yard of neatly manicured gardens surrounding a nondescript white building.

The sign above the door has the gleam of a recent addition: Depósito Central de Vacinas.

This is Angola’s vaccine depository, a crucial lynchpin in its distribution system.

The health minister says the country started ordering fridges and planning a distribution network last year. A country must show it can store vaccines before it can receive them under the global vaccine-sharing program COVAX, and Angolan officials tried to prepare for anything — including a host of different vaccines with different storage requirements.

“All over the country, we can vaccinate with Pfizer, we can vaccinate with Sinopharm, we can vaccinate with AstraZeneca, we can vaccinate with Johnson and Johnson,” she said, speaking through a translator.

“We can vaccinate with any other vaccine.”

Given that some countries struggle to pay for and distribute typical childhood vaccines, the challenge of distributing COVID vaccine has pushed some health-care systems to the brink.

COVAX has tasked UNICEF, a branch of the United Nations that already provides aid to children around the world, with delivering donated vaccines as far as the local airport, at which point it’s largely the recipient country’s problem. (That said, UNICEF is also doing its own work in dozens of middle- and low-income countries, including things such as training and providing personal protective equipment to health workers and combating vaccine hesitancy.)

The challenge has been complicated by the fact that the size of shipments has varied and they have arrived on nothing resembling a set schedule. Wealthy countries have also used COVAX as a defacto clearing house for vaccines they can no longer use, some of which have been redistributed, as one observer put it, with all the organization and planning of someone regifting last year’s Christmas present.

In an email, a COVAX spokesperson said that vaccines are “ideally” allocated three months ahead to account for things such as expiry dates and how many vaccines a country can reasonably expect to use.

Before a donation ships out, countries must grant national regulatory approval for the vaccine, and complete “readiness checklists” to show they can store and transport the doses. They must also sign a “manufacturer-specific indemnity and liability agreement,” which limits the vaccine makers’ responsibility for things like adverse effects.

While this isn’t unheard of during a pandemic, some countries have accused the makers of COVID vaccines of taking it too far — according to the U.K.-based Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Argentina accused Pfizer of asking for indemnity for, among other things, its own negligence. Pfizer was quoted in the story as saying it had allocated doses to low- and middle-income countries for a not-for-profit price and was “committed” to supporting efforts to promote global vaccine access.

Ultimately a recipient country can choose to take a donation or not. Poor nations rejected more than 100 million vaccine doses in December alone, mostly because they were too close to their expiry date, a UNICEF official told Reuters. Other countries have struggled to string together enough refrigeration capacity to keep the vaccines chilled to manufacturers’ specifications.

In an interview with the Star, Harjit Sajjan, the newly minted federal minister of international development, says officials are currently moving “as quickly as possible” to assist the global community.

Sajjan, who did three tours in Afghanistan as a military reserve officer, says it’s important that donations and other supports are tailored to the needs on the ground, and that broader issues around a country’s ability to accept and use vaccines are addressed. Maybe some countries aren’t ready to transport vaccines, or don’t have enough refrigerators standing by, he says.

He points to countries that donated excess doses to low-income countries, only to see them tossed because they were too close to expiry: “It sounds all great from a political perspective. But we just wasted all those doses,” he said.

An official with UNICEF involved in shipments to this part of the world says that when he emails Angolan leadership to ask if they can handle another arrival, their only question is — how soon can it get here?

Angola was the first country in southern Africa to welcome a COVAX shipment, in March 2021.

The country has a population roughly the same size as Canada’s, but with not quite four per cent of the gross domestic product. That number papers over a stark divide between the haves and have notes — Luanda ranks among the world’s priciest cities for foreigners who pay $400 a night in high-end hotels and lounge at beach clubs while en route to offshore oil rigs.

Meanwhile, almost half of the population lives on less than $2.50 a day. While Canada called in the army to make sure regular shipments of three vaccines were shuttled across the country, Angola has handled half a dozen different vaccines on a shoestring budget.

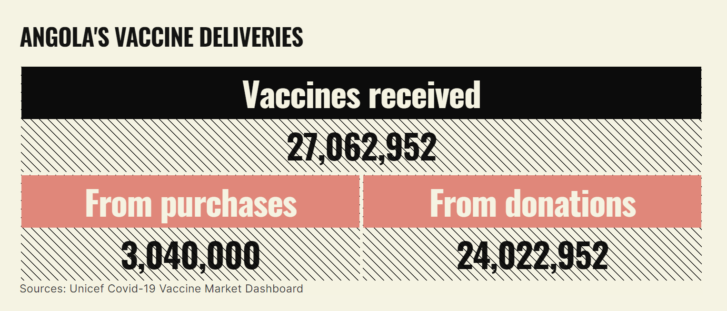

Angola is one of 92 countries classified as “low” or “low-middle” income by COVAX, and it has been mostly dependent on donations, despite managing to pay for some vaccines. The country has received donations well known in the West, including Pfizer, Moderna and Janssen, but also shots less familiar to a Western audience, including Sinopharm from China.

Roughly a dozen countries have chipped in donations, according to UNICEF’s vaccine tracker. Portugal, Angola’s former colonial ruler, has sent at least three types of vaccine, including more than 700,00 AstraZeneca doses from its own supply. Even Alrosa, a Russian mining company that owns almost a third of a massive open-pit diamond mine known as the Catoca mine, announced it was sending 50,000 doses of Russia’s Sputnik V shot.

Inside the vaccine depository, the AstraZeneca vaccines have their own room, cooled exactly to the manufacturer’s specifications. The woman in charge pulls out a phone and taps open an app that shows the temperature of each room: “Even from home, I can see whether there is a problem or not.”

They’re taking no chances. The stakes are too high.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

The COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility, quickly shortened to the more pronounceable “COVAX,” was announced with much fanfare in April 2020 at a meeting hosted by the World Health Organization and including a who’s who of leaders from around the globe.

The initial goal of delivering two billion vaccines by the end of 2021 died early and decisively.

COVAX had initially hoped to act as a purchasing mechanism for the world, whereby wealthy countries could effectively pool their money to fund the development and purchase of vaccines, which would, in turn, help fund doses for their low-income neighbours. The goal then was to send roughly a billion vaccines to high income countries, and a billion to poorer countries.

But when it became clear that wealthy countries were choosing to cut their own deals instead, COVAX jettisoned the first part of its mandate and decided to focus just on low-income countries.

In mid-January 2022, COVAX celebrated the one billion milestone. The news release announcing the milestone started out celebratory before taking a turn: “COVAX’s ambition was compromised by hoarding/stockpiling in rich countries, catastrophic outbreaks leading to borders and supply being locked,” it reads.

The initiative has now found itself cash-strapped. In January of 2022, organizers put out a call for $5.2 billion US in new funding to cover the costs of actually getting some of these doses into arms, like syringes and transport, as well as unexpected costs of booster shots or vaccines tweaked for new variants.

In the first week, it raised three per cent of that goal.

To be clear, Canadian leaders haven’t ignored the rest of the world.

In a year-end interview with the CBC, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that getting vaccines to the rest of the world will be one of the clearest signs that the pandemic is in its end stages.

He pointed out that Canada was one of the first to commit to COVAX, the only global attempt to make sure vaccines were distributed equally, and that “making sure that we’re ending COVID everywhere so it can be over anywhere,” was a priority.

Yet Canada has fallen far short of its promises.

In 2021, Trudeau pledged to donate 50 million shots from Canada’s supply and pay for at least 150 million more through money given directly to COVAX. Though a firm commitment to export excess doses wasn’t made until July — seven months after the most vulnerable Canadians started getting shots — and the vials didn’t actually get delivered to COVAX until September.

By the end of the year Canada had only donated a quarter of the doses it had committed to — or about 12.7 million shots — and provided enough money, about $545 million in cash, to buy an additional 87 million.

Since the national advisory body recommened all adults in Canada get a booster shot in the first week of December, more than a million doses of vaccine have landed on Canadian soil every week — in total, more shots have come to Canada since then than were donated abroad all of last year.

This lopsided global vaccine distribution is not simply the age-old tale of rich outbuying the poor. Even some lower income countries that tried to buy their own doses say they found themselves pushed out of line by wealthier countries.

In Rwanda, former health minister Agnes Binagwaho’s irritation is palpable. A no-nonsense pediatrician who has, among other things, taught at Harvard, Binagwaho returned to her home country after the genocide in 1995, where she presided over a hospital system that is rapidly becoming one of the best on the continent. Now the country that has rebuilt itself from ashes is being held back by a lack of vaccines.

As she tells it, Rwanda was ready and waiting to distribute vaccines. The problem has been getting them. “There is no vaccine to buy,” she says simply, speaking in September over a video call from Kigali.

“We have paid for 3.4 million doses of Pfizer,” she says. “We paid upfront at the beginning. That’s been more than a year ago. Same for AstraZeneca, 500,000 doses.” (According to the UNICEF online tracker, Rwanda had recieved at least that many doses through COVAX by the end of 2021, though some of their biggest shipments had arrived in the later months of the year.)

The New York Times reported last fall that Botswana had ordered half a million doses from Moderna that were due to arrive in August, but has been left waiting. According to Doctors Without Borders, the Central African Republic had also been promised doses by COVAX that arrived months later than expected.

“Those big pharma prefer to serve rich counties, even if they’re orders come after low income countries,” Binagwaho says, speaking over a video feed from Kigali. “Normally, such a practice would have been condemned.”

In an emailed response, a spokesperson for Pfizer said that their vaccine doses “are shipped based upon the supply agreements in place with the government or supranational organization. From day one of our vaccine development program, our outreach has been broad and inclusive to ensure equitable access.”

The vaccine supply shortages have raised questions about how useful funding is by itself — last fall Switzerland became the first country, and, so far, one of the only — to give its place in Moderna’s manufacturing queue to COVAX, allowing the initiative to take delivery of a million shots while the small European country waited.

Meanwhile, Canada has sat firmly on the fence in response to a push from South Africa and India to temporarily waive vaccine makers’ intellectual property rights, therefore giving other manufacturers a chance to start churning out the life saving doses.

The result? Prevented from buying or making their own vaccines, much of the world is now dependant on a system of charitable handouts that, so far, hasn’t panned out.

An Angus Reid poll released last June suggested that sharing doses overseas too soon would be politically unpopular, with almost three quarters of Canadians saying they wanted officials to wait until all eligible adults and teens had been vaccinated here before doses were sent abroad.

But, if the argument for helping neighbours doesn’t warm your heart — there’s a selfish rationale to sharing vaccines, too.

Dr. Madhukar Pai, the Canada Research Chair in epidemiology and global health, based at McGill University, points out that every infected person harbours between one and 100 billion viral particles at peak infection — little virus bitties that can be spewed into the air with every cough or sneeze.

They also replicate by, essentially, copy and pasting themselves; and every time they do so, they risk making a mistake. It was a mutation like this that birthed Omicron, and it will be a mutation like this that creates the next variant, too. That next variant could be worse.

Pai has been one of the loudest voices in Canada pushing for vaccine equity. He hopes that Omicron could be the watershed moment at which Canadians finally realize that they won’t be safe until other countries are, too. But for months, he’s given interview after interview, shouting into the void, and now, he apologizes if his words have been sharpened by frustration. Optimism is in short supply.

“Look at the prime minister. His comments (about vaccinating the world) are brilliant. I could have written them for him,” Pai says.

“But, is he following up on them, is my question. That’s what I want to know. Show me action, not words. Words are cheap.”

The oldest landmark in Luanda may be the Fortress of São Miguel, which has clung to the coast like a barnacle for almost half a millennium.

Built by the Portugese and named for the angel tasked with championing the Catholic church, its canons are still trained on the whitecapped waters of the Atlantic — the same waters over which generations of people were taken in chains to the Americas and where, more recently, deep water oil reserves have begun to gush revenues into the fledgling country’s coffers.

Even for a part of the world often dismissed by outsiders as war-torn, Angola’s history is particularly violent. Portugese ships first sailed into view over four centuries ago, and the then-mighty colonial power grew coffee and gutted communities for slaves.

Nationalist fighters won freedom in 1975, but the country fell almost immediately into a civil war that attracted the notice of the major players of the Cold War, from the United States and the U.S.S.R. to China and South Africa, who poured money and munitions into opposing sides, turning the newly freed nation into their own military chessboard.

Decades of fighting in the desert and the jungle pushed people into the capital, and, today, Angola is one of the most urbanized countries in Africa. The old fortress has been joined in the skyline by the domed national assembly and the towering mausoleum where the country’s first president — a man known as much for his poetry as his politics — has been laid to rest.

As more people have flooded in, the imposing colonial buildings, many improbably-pink, became hemmed in by the shops, office buildings and honking weekday traffic that mushroomed up in every available space.

The country has been peaceful now for two decades, and the country has struggled mightily in recent years to knit the social fabric back together. Children born in 2019 were expected to live 20 years longer and get eight more years of schooling than their parents.

Life in low income countries can feel more precarious, without the safety net afforded by the resources of a wealthier nation. But COVID has thrown a wrench into the rise of a country working to overcome the past, and right now, there’s no end in sight.

Angola has a population roughly the same size as Canada’s (almost 33 million people compared to Canada’s 38 million), but if you go by the official numbers has had a fraction of the cases — roughly 80,000 people confirmed sick, versus 2.3 million cases in Canada.

Observers point out that when a PCR test at a pharmacy can cost a month’s salary, that number is almost certainly an underestimation. Over the same time period, one notes, the number of graves dug has tripled.

When you drive out of downtown, the buildings get lower and start to crowd together.

More than half of Angolans who live in cities live in informal settlements known as “musseques,” that splash up hillsides and down roadways at the margins of the city. The close quarters can mean a half dozen people living in a couple of rooms, with limited access to water and electricity.

In an area called Bairro Gika, a faucet built into a dugout in the iron-red earth gushes, clear and cold, for hours every day as women take turns filling up plastic containers of every shape and size before lifting them, one by one, onto their heads, to be carried to their households.

These tight-knit communities have mushroomed up over time, the ad hoc brick buildings growing and changing to meet the needs of those who live among them. Within that, the taps seem to be part critical infrastructure and part communal water cooler.

Women stop by to chat, the babies on their backs blissfully asleep; kids run by, the shell-shaped beads in their hair clicking with every step, and a vendor rolls through a wheelbarrow of dried fish.

The staff of the non-governmental organization Development Workshop has spent years trying to bring water to these areas through the creation of communal taps, where dozens of local residents could come and fill up.

But when the virus began to spread, it was feared that these water points would become vectors of disease. Funded in part by the Canadian government, Development Workshop set about modifying some of these water points to try and make them COVID friendly.

SAFEGUARDING ANGOLA’S VITAL WATER POINTS

Before the pandemic, Lufunda Yona worked as a driver, but COVID lockdowns had put him out of work. He grew up in Gika, and has been hired on as one of the builders of the new project, and is here today to pore over plans and inspect the sheets of metal that will be used to erect the new shelter.

When he was a kid, most people here lived in tents or small wooden houses, but over the past couple of decades, the neighbourhood remade itself in concrete blocks. People continued to pour in.

When COVID hit, “so many people lost their jobs and that affected many people,” he says, through a translator. Finding a job had been hard before, but now it’s even tougher.

Yona is vaccinated and is hopeful the shots could eventually pave a way out of the pandemic. But it’s difficult for a lot of his neighbours to travel all the way to a vaccine clinic, he says — he wishes it were easier for people out here, in the outskirts, to access one.

These communities were particularly vulnerable to a virus that spread among people in close quarters.

Early in the pandemic, Development Workshop called roughly 1,600 people in 18 Angolan provinces and found that while income dropped drastically, cost of living went up, leaving people increasingly without the funds to buy even simple things such as hand sanitizer or medicine

Angola’s pandemic response is orchestrated out of the upper levels of a shiny tower in downtown Luanda — one originally constructed for a Chinese resource company — filled with polished wood and oversized furniture.

The country convened a special committee of politicians and staffers to lead the COVID response early on, and their conference room table is surrounded by charts and maps covered in blue erasable marker that track cases and deaths in each region, while a TV screen shows cases in other countries.

Lutucuta, the cardiologist turned health minister, says government officials knew from the beginning that walking up to the makers of AstraZeneca and Pfizer and placing an order was going to be a non-starter, given the expense and the intense competition among richer countries. So, they took what they could get.

“The country can’t wait, so we had to look for opportunities that can supply us in a short period of time,” she says.

While the country wasn’t able to get its own contracts with the makers of the mRNA vaccines, it was able to make a limited order for a Chinese dose, she says.

Officials also decided that the benefits of the AstraZeneca vaccine outweighed any concerns — though they stress they’re watching for side effects closely — so unlike some countries that have expressed trepidation, Angola has welcomed donations of the shot with open arms.

When neighbouring Congo paused use of the dose, one official said, Angola scooped that country’s up and used it, too.

The World Health Organization had set the goal of getting 40 per cent of every country vaccinated with two shots by the end of 2021. Determined not to waste a drop, Angola hoped to exceed that.

Just seven countries in Africa met that goal. Fewer than half made it higher than 10 per cent.

Angola made it to 12 per cent.

They’ve come in suits and head wraps and long, flowing dresses, toting babies, bobbing gently to headphones; but they’ve all come with a single purpose.

The news had blared on national radio and pinged out via text message across Luanda, the bustling seaside capital of Angola, the night before: a new shipment of COVID vaccines has arrived, the bulk of which was paid for by Canada.

People heeded the call, forming tidy lines on the rusty red soil outside teachers’ colleges and decommissioned libraries and zigzagging across the parking lot of the Estádio da Cidadela, the former national stadium of Angola, where the striker known as Akwá — arguably the country’s most famous soccer player — scored his way to dominance two decades ago, even if the concrete cathedral has lost some sheen since then.

Inside the stadium, a vaccination site has been set up across two basketball courts. One of the women in charge, Esperanza Belo, wearing a blue vest marking her as an employee of the health ministry, says sometimes that when they have vaccines her staff doesn’t leave before 11 p.m.

“As you can see, we have long lines outside,” she says, through a translator, motioning to the door beyond the empty nets. “If we see people we can’t leave them outside. All these people will be vaccinated.”

Some will wait hours in the muggy heat at these vaccination sites, hoping for a shot before the well once again runs dry. Officials estimate the Canadian shipment will last about a week.

This morning, Germane Lumana’s phone rang early — it was her sister-in-law, who’d heard about the new shipment of vaccines and knew Lumana had been waiting for a second shot of AstraZeneca. Lumana didn’t waste any time, throwing on a black T-shirt and a ball cap before heading out the door.

The wheels of this country’s young, bustling, cacophonous economy are still greased by informal business. It’s possible to buy everything from multicoloured push brooms to pineapples to masks from vendors standing on street corners, and Lumana is part of the army of self-employed.

She makes kwanga, a bread made from boiled cassava, and sells it from home. The pandemic has pushed people like her into economic free fall, doubly so now that proof of vaccination is required to enter many businesses and public spaces.

The nearest vaccination site to her was assembled in an event complex, with doses being given out in multiple rooms, including a ballroom that looks more suited to a black tie dinner. This morning she will be injected with a marvel of modern medicine — a vaccine designed in Britain, manufactured in Sweden, which will instruct her own cells to make a fake version of the famous spike protein, and set her up to be protected from the real thing.

Perched in a plastic chair in this ballroom turned mass vaccination site, she doesn’t flinch as a blue-gowned staffer gives her the shot. Only after it’s done does she look down briefly down at her arm, before standing up.

“I’m a free woman,” she says, her eyes betraying the grin her medical mask hides. “I can go anywhere.”

Today, Lumana is lucky. Next week the shots will be gone, and Angola’s wait for its next shipment will begin.

Article From: The Star

Author: Alex Boyd Toronto Star