Key Take-Home Messages

- COVID-19 is associated with increased rates of common mental disorders.

- There are higher rates of increased mental disorders for young individuals and for girls and females.

- There is some evidence of higher rates of alcohol use, especially among those with prior harmful drinking.

- So far, few data show time trends and relationships with COVID-19 infection peaks and waves.

- To date, no clear evidence exists of raised suicide rates.

- Beware of overgeneralizations.

- Health and social care staff are at higher risk of common mental disorders.

- Protective factors include social support and prompt government action.

At press time, COVID-19 had infected more than 234 million people worldwide and contributed to at least 4.7 million deaths.1 Although most of the research on the vast human toll of COVID-19 has referred to death and physical morbidity, analysis of the mental health consequences of the pandemic has surged, with more than 3000 relevant papers and more than 120 review papers published in the past year. This article addresses 4 key issues: (1) impacts on the general population; (2) impacts on individuals with preexisting mental illness; (3) impacts on individuals providing essential services; and (4) impacts on individuals infected with COVID-19.

Although the figures cited in this paper are from different countries, the conclusions may not be generalizable, as regions, continents, and countries have shown somewhat different characteristics in their experience of the pandemic. This is especially true regarding differences between high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Similarly, important variations (ie, family, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic factors and issues) exist within components of the general population that may differentially affect the impact of the pandemic. Thus, this article provides perspectives but is not intended to be an exhaustive review.

Impacts on the General Population

The early consequences of the threat of COVID-19 infection in spring 2020 produced many features of “health anxiety.” There were elevated rates of insomnia, anxiety, and depression; reports of increased alcohol and drug use; and, somewhat understandably, antisocial behaviors such as excessive stockpiling of essential supplies. Increasing numbers of individuals within the general population were directly affected by grief following the deaths of people they loved.

Even in the pandemic’s early months, it was clear that it would be important not to overgeneralize. Data from the United Nations (UN) in mid-2020 showed that, in national surveys, distress was identified among the general population in several countries to differing extents—for example, 35%, 45%, and 60% in China, the United States, and Iran, respectively. During 2021, several systematic reviews were published on the mental health impacts on whole population. These studies found pooled prevalence rates for anxiety of between 32% and 34%, and for depression of 30% to 31%.2,3 These papers also identified risk factors for even higher rates of common mental disorders—namely, preexisting chronic disease, being quarantined, or being infected with COVID-19.

In the United Kingdom, data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) showed higher rates of and greater increases in depression among people aged 16 to 39 years, rising from 10.9% in 2019 to 31% in 2020, with the lowest rates of depression in 2020 among individuals 70 years or older. These ONS surveys also demonstrated that the increase in the rates of depression differed by gender, with prevalence rates in spring 2021 for women and men aged 16 to 29 years at 43% and 26%, respectively. The harm to mental health may also be even greater for students, as a systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that 36% and 39% of students were experiencing anxiety and depression, respectively, after the start of the pandemic.4

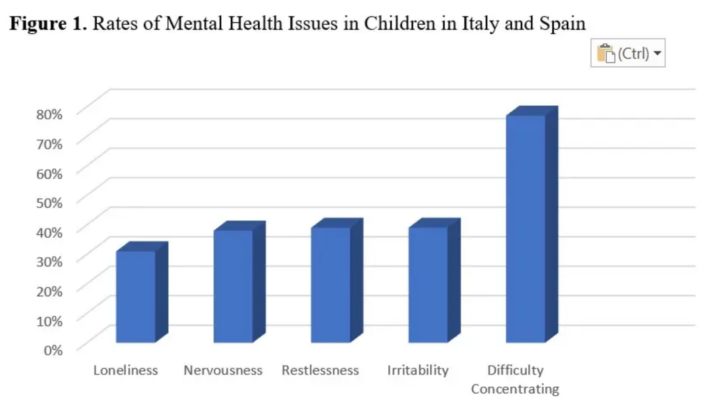

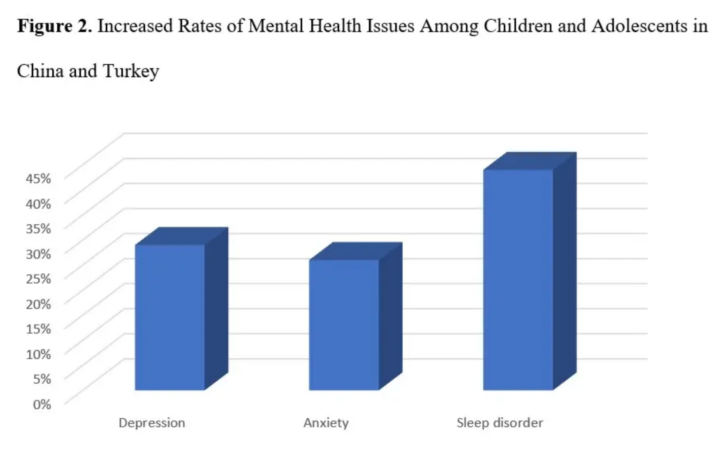

The effects of the pandemic on the mental health of children and young people also seem to be harsh. In mid-2020, UN data indicated that among children in Italy and Spain, the 2 countries hit hardest early in that year, there were high rates of loneliness, nervousness, restlessness, irritability, and difficulty in concentrating (Figure 1). ONS data in the United Kingdom again found differences between genders: Among adolescents aged 11 to 16 years, mental health problems were found in 15% of boys and 20% of girls in 2020. A wider analysis of the impact on children and adolescents in China and Turkey found increased rates of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorder, once again higher among girls (Figure 2).5

These findings were reinforced by a global review of the literature, which found the following protective factors: social support, coping skills, home quarantining, and parent-child discussions.6 On the other hand, groups vulnerable to greater mental health harm may include children with special needs, those with a preexisting mental disorder, and young people with excessive media and social media exposure.7 Once again, caution is needed in interpreting these results, as some reports suggest large variations in the impact on young people among countries.8

Early in the pandemic, a number of commentators held the view that the devastating economic impact of COVID-19 across the world would lead to an increase in suicide rates, based in part upon evidence from the 2008-2010 recession and associated economic austerity measures. In fact, the evidence to date does not support this concern. An analysis of data from 21 high- and upper-middle-income countries worldwide found that suicide rates remained largely unchanged or declined in the early months of the pandemic compared with the expected levels based on the prepandemic period, but the authors also indicated a need to “remain vigilant and be poised to respond if the situation changes as the longer-term mental health and economic effects of the pandemic unfold.”9

Governmental actions at the national level may also mitigate or exacerbate mental health impacts. A fascinating paper using data from 33 countries showed that overall depression incidence among adults was 21% during 2020, but rates tended to be lower in countries whose governments reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic with prompt and stringent control measures.10

Impacts on Individuals with Preexisting Mental Illness

From the outset of the pandemic, there were clear grounds to be fearful that the impact on people with preexisting mental illness would be greater than on the whole population. This concern is based on a number of factors: the high rates of coexisting physical and mental morbidities; the risk of cross-infection in wards, homes, or other institutions; the lower priorities given to patients with mental illness for reasons associated with stigma11; and concerns about reduced funding for mental illness services to offset spending increases for direct COVID-19 services. Subsequent evidence largely supports these fears. One particular concern refers to higher mortality rates from COVID-19 among psychiatric patients, reported to be between 1.4 and 7.6 times higher than that of patients without mental illness,12,13 with exposure to antipsychotic medication as a particular risk factor.14,15 Further evidence of this concern is reflected in The Economist, which reported that public health data from England indicated that mortality rates from COVID-19 are about 4 times higher in individuals with learning/intellectual disabilities, especially older individuals, than among the general population.16

Impacts on Individuals Providing Essential Services

Perhaps the starkest rise in the occurrence of mental disorders has been identified among individuals providing essential services. It is important to remember that essential workers across the globe are heterogenous, with different risks, backgrounds, support, and cultures. Studies vary in their definitions of this group: Narrow criteria may include only health care workers while wider criteria may include, for example, public transport workers, truck drivers transporting essential supplies, and shopkeepers. Several factors combine to put these workers at higher risk: canceled days off or holidays; multiple experiences of loss and bereavement for intensive/critical care staff; and the moral hazards of being asked to prioritize patients to receive potentially lifesaving interventions.

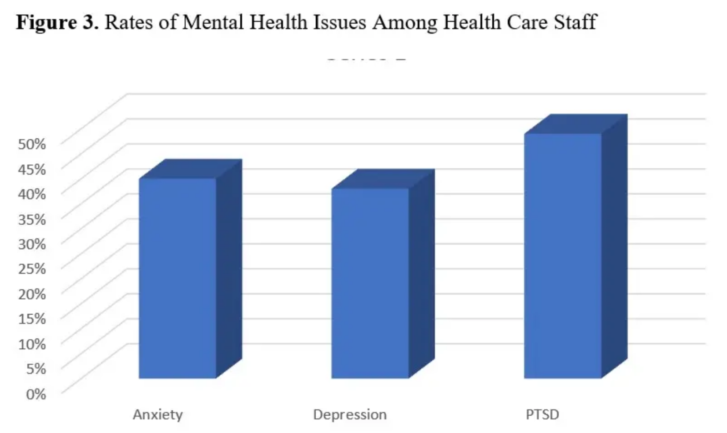

A survey by the COVID Trauma Response Working Group in the United Kingdom conducted in spring 2020 found that among 1194 employees in frontline health and social care positions, 47%, 47%, and 22% met criteria for anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), respectively. Most staff (58%) met the criteria for at least 1 of these conditions.17 At the global level, a systematic review of 38 relevant studies reported pooled rates of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among health care staff (Figure 3).18 It is clear that the aggregate impact of COVID-19 on health and social care staff is among the most pressing continuing challenges of the pandemic. It has not yet received sufficient response.

Impacts on Individuals Infected by the Coronavirus

The mental health associations and consequences of COVID-19 infection seem to be becoming clear more slowly than in the other scenarios mentioned. The emotional and mental health consequences include the early impacts of self-isolation and quarantining, which are linked with higher rates of anxiety and depression.

Acute COVID-19 infections can be characterized by a plethora of psychiatric indicators, including delirium and psychotic symptoms.19 An estimated 20% to 35% of inpatients with COVID-19 have associated features of mental state while being treated for COVID-19. Postinfection features of long COVID are, as yet, not clearly characterized; no agreed-upon definition of this syndrome has been formalized. However, these features often include elevated rates of anxiety, depression, brain fog, and fatigue, such that this pattern of difficulties is increasingly being compared with chronic fatigue syndrome. Patients with COVID-19 who received hospital ventilator support have particularly high subsequent rates of PTSD.20

Interestingly, psychiatric sequelae seem to occur more often after COVID-19 infection than after other viral infections, with 5.8% of COVID-19 infections leading to a first onset of a psychiatric disorder within the following 3 months, compared with 2.8% of influenza cases, according to University of Oxford data. Indeed, several researchers now take the view that there are bidirectional influences between COVID-19 and mental disorders, with a recent paper suggesting that “survivors of COVID-19 appear to be at increased risk of psychiatric sequelae, and a psychiatric diagnosis might be an independent risk factor for COVID-19.”21 It also needs to be recognized that stigmatization and discrimination against people associated with COVID-19 is a continuing scourge.22

Conclusions

Several general lessons emerge from this overview of the voluminous research on the complex associations between COVID-19 and mental health. It is clear that in the general population—at least during the first year of the pandemic—there were substantial rises in the rates of anxiety and depression, and these were more marked for young people and for women and girls, as previously discussed. There is also some evidence of greater alcohol use, especially for individuals with preexisting harmful alcohol use.23 As yet, we do not have clear signals about whether these higher rates covary with peaks and troughs of COVID-19 infections, or whether vaccinations offer protective effects. Currently, no clear global evidence exists of elevated suicide rates as a consequence of the pandemic or associated economic austerity. However, we need to be cautious about not overgeneralizing from the available studies, as these rates seem to vary considerably across countries. It is clear that health and social care staff as well as other key workers and essential personnel have worryingly high levels of common mental disorders, jeopardizing their ability to carry out and sustain their essential roles. Protective factors are increasingly being identified by research, and these include direct social support, discussions between parents and children, and possibly prompt and vigorous action against infection waves.

As in most domains of mental health research, the large majority of the COVID-19 literature comes from high-income countries although about 85% of the world population lives in LMICs.24 Clearly, the abilities of health care systems in LMICs to respond to the pandemic are dramatically weaker than those of wealthier nations.25,26 Prior to the pandemic, the gap between mental health needs and the provision of care (called the “mental health gap”) was vast. For example, among individuals with major depression in LMICS, only 1 in 27 received effective care.27 An early rapid review by the World Health Organization identified the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health services in about 100 countries worldwide and found that most experienced service disruptions, including reductions in essential emergency and lifesaving mental health care.28 This raises the clear possibly that the mental health gap may well increase during and after the pandemic. Thus, it would be interesting to see a deep dive into specific issues in different areas of the world (eg, Latin America, Asia, Africa, etc); such a discussion is beyond the scope of this paper.

Even so, emerging innovations, such as the rapid transition to remote methods of consulting, have the potential to positively transform mental health service delivery in LMICs and worldwide.29,30 It is clear, for all the reasons given in this article and by the UN, that determined and concerted action is needed to properly and sustainably respond to the global COVID-19 mental health crisis.31

Dr Thornicroft is a professor of community psychiatry at the Centre for Global Mental Health and the Centre for Implementation Science, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London. He also works as a consultant psychiatrist at the South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust in a local community mental health team. He is a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences; a National Institute of Health Research Senior Investigator Emeritus; and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, King’s College London, and the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

References

1. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. World Health Organization. 2021.

2. Chekole YA, Abate SM. Global prevalence and determinants of mental health disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;68:102634.

3. Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:91-98.

4. Li Y, Wang A, Wu Y, Han N, Huang H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:669119.

5. Ma L, Mazidi M, Li K, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:78-89.

6. Jones EAK, Mitra AK, Bhuiyan AR. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2470.

7. Panchal U, Salazar de Pablo G, Franco M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Published online August 18, 2021.

8. Porter C, Favara M, Hittmeyer A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression symptoms of young people in the global south: evidence from a four-country cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e049653.

9. Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(7):579-588. Published corrections appear in Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(8):e18; and Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(11):e21.

10. Lee Y, Lui LMW, Chen-Li D, et al. Government response moderates the mental health impact of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of depression outcomes across countries. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:364-377.

11. Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health–related stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1123-1132.

12. Fond G, Nemani K, Etchecopar-Etchart D, et al. Association between mental health disorders and mortality among patients with COVID-19 in 7 countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(11):1208-1217.

13. Wang QQ, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):124-130.

14. Vai B, Gennaro Mazza M, Delli Colli C, et al. Mental disorders and risk of COVID-19–related mortality, hospitalisation, and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(9):797-812.

15. Ostuzzi G, Papola D, Gastaldon C, et al. Safety of psychotropic medications in people with COVID-19: evidence review and practical recommendations. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2020;18(4):466-481.

16. Learning-disabled Britons are the pandemic’s forgotten victims. The Economist. December 10, 2020.

17. Greene T, Harju-Seppänen J, Adeniji M, et al. Predictors and rates of PTSD, depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during COVID-19. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12(1):1882781.

18. Saragih ID, Tonapa SI, Saragih IS, et al. Global prevalence of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;121:104002.

19. Banerjee D, Viswanath B. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 and possible pathogenic mechanisms: insights from other coronaviruses. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102350.

20. Chamberlain SR, Grant JE, Trender W, Hellyer P, Hampshire A. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in COVID-19 survivors: online population survey. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(2):e47.

21. Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):130-140.

22. Gronholm PC, Nosé M, van Brakel WH, et al. Reducing stigma and discrimination associated with COVID-19: early stage pandemic rapid review and practical recommendations. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e15.

23. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942.

24. Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Gureje O. The differential outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in low- and middle-income countries vs high-income countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1207-1208.

25. Maulik PK, Thornicroft G, Saxena S. Roadmap to strengthen global mental health systems to tackle the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:57.

26. Yue J-L, Yan W, Sun Y-K, et al. Mental health services for infectious disease outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Psychol Med. 2020;50(15):2498-2513.

27. Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(2):119-124.

28. The impact of COVID-19 on mental, neurological and substance use services: results of a rapid assessment. World Health Organization. 2020.

29. Kola L, Kohrt BA, Hanlon C, et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(6):535-550. Published correction appears in Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):e13.

30. Vigo D, Patten S, Pajer K, et al. Mental health of communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(10):681-687.

31. United Nations. COVID-19 and the need for action on mental health. United Nations. 2020.

Article From: Psychiatric Times