The province is scrapping its vaccine certificates. But data suggests certificates helped “change the trajectory” in the fall.

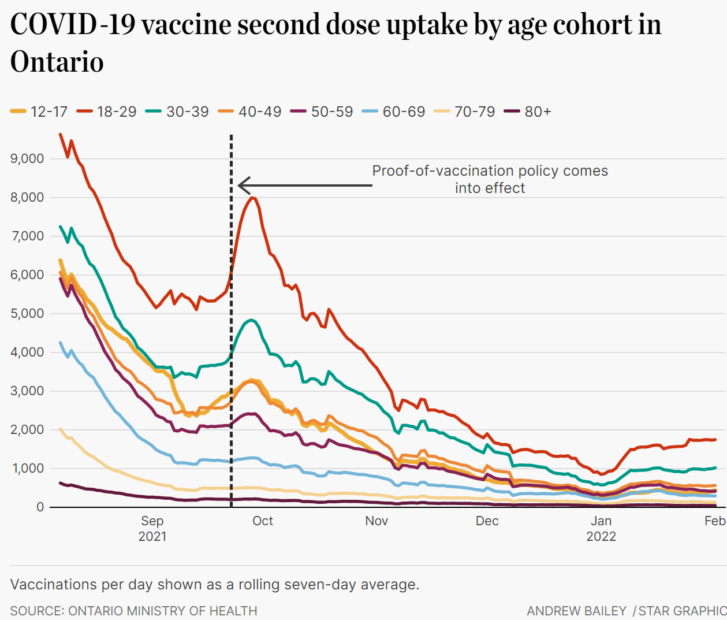

The introduction of a proof-of-vaccination policy in Ontario last fall for entry into venues such as restaurants, bars and gyms was followed by a noticeable bump in second-dose COVID-19 vaccinations, particularly among younger age cohorts, a Star analysis has found.

Data from September to December 2021 shows vaccination rates for the 18-29 and 30-39 age groups had the steepest increases after the province implemented the vaccine passport program — a signal that suggests the policy may have nudged some people towards getting their second shot.

But whether people went out to get their second dose as a direct response to the policy is a complicated question, experts caution.

Vaccine passports have been a hot topic in recent days with several provinces, including Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan and Alberta announcing the end of proof-of-vaccination programs as public patience with restrictions wears thin and COVID hospitalizations trend downwards.

“There’s a reason why vaccine mandates were in place and that’s because they’re an evidence-based approach to improving vaccine uptake,” said Laura Rosella, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health. “It’s well established that the mandates in lots of jurisdictions actually do contribute to uptake in vaccinations.”

The question that’s less clear, said Rosella, is why.

“It’s not just when people are forced that they do it. It could also be, ‘oh, this might actually be really important, I’d better get around to doing it.’ It’s not that everyone’s vaccine-hesitant,” she said. “Often it’s nudging people that either were intending to do it or they weren’t feeling strong one way or the other, or even encouraging people to reach out to their health-care provider to have a conversation about the benefits of the vaccine.”

The Star looked at seven-day rolling averages for daily second doses last fall, broken down by age group, using data publicly available from the Ministry of Health.

This shows that about three weeks after the province announced proof-of-vaccination requirements for entry into public places, vaccinations in most age cohorts saw sharp increases over a period of about 10 days. The only age groups that did not register increases were those 70 and older, most of whom became eligible for second doses earlier in the year.

The seven-day average number of Ontarians who received a second dose every day in the week preceding the implementation of the proof-of-vaccination policy was 18,823, according to provincial data analyzed by Dr. Peter Jüni, scientific director of Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. That average increased to 23,790 second doses per day in the week from Sept. 22-28 — a 26 per cent increase.

Jüni said such an increase in vaccination uptake does not prove causality but said it is “very suggestive that the implementation of certificates helped us to change the trajectory we were on. We saw continued flattening of the curve of vaccine uptake before this was implemented, and then it got steeper again.”

Recent studies have shown that vaccine uptake increased in other jurisdictions following the introduction of similar policies.SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Researchers at the Saskatchewan Population Health and Evaluation Research Unit found that the proof-of-vaccination policy in that province had a “significant” but not “sustained” impact on both first and second doses, following the announcement of the requirement in September 2021.

Just last month, the number of first-dose appointments in Quebec quadrupled to more than 6,000 per day from 1,500, after Health Minister Christian Dubé announced that proof of vaccination would have to be shown to enter provincial liquor and cannabis stores. But these measures were lifted this past week, and the province plans to drop all vaccine passport requirements by March 14.

A January 2022 study published in The Lancet Public Health compared vaccine mandates in five European countries, plus Israel, and found that proof-of-vaccination certificates led to an increase in shots 20 days before the policy was implemented, with the effect lasting up to 40 days. There was a more pronounced impact in countries that had below-average vaccination rates.

Sara Allin, an associate professor at the Dalla Lana school, noted that there also seemed to be a small bump in Ontario’s daily second doses around the time that the U.S. land border opened to fully vaccinated Canadians for recreational travel, on Nov. 8.

There were a lot of other incentives in early fall to increase vaccination rates, including university and college vaccine mandates, she added, as well as intense local efforts to make vaccines more accessible, such as pop-up and apartment clinics. Some employers and businesses also introduced vaccine requirements for employees around that time.

“It’s interesting that this is kind of supported by data coming out of other provinces like Saskatchewan,” she said, “and I think that’s fairly compelling.”

However, she said she wants to research this further to look at other variables, such as where people who got shots post-vaccine passport live.

“I would also be interested in looking at how these policy changes impact the equitable uptake,” she added. “So, are we reaching those who are more likely to benefit?”

Jüni noted that the proof-of-vaccination system that Ontario is soon to eliminate does not currently have the capability to register a recent Omicron infection — in addition to two doses of the vaccine — which a growing body of evidence suggests is equivalent to three doses.

The feasibility of somehow adding a recent infection to a vaccine certificate, instead of a third dose, is problematic with the existing limitations to public lab testing, he said.

“It’s difficult to implement,” he said. “In this situation, I’d rather say we drop the certificates and keep them in the back pocket for future use if we need them again, because we need to be aware that this pandemic is not just over because we pretend it’s over.”

Article From: The Star

Authors: Kenyon Wallace, May Warren