The goal was daunting, seemingly unattainable: Vaccinate 90 per cent of Ontario’s population — more than 13 million people — against COVID-19.

Double doses would help protect our family and neighbours, lower our own risk of getting sick and push us past the pandemic that has upended daily life and led to the deaths of more than 10,000 people in the province.

Thousands took on the monumental task. Health-care providers. Community leaders. Public health workers. Logistics experts. Pharmacists. Countless volunteers.

The campaign began in long-term-care homes, a race to protect the most vulnerable. Limited vaccine supply meant the spring rollout started out rocky. But the summer blitz saw millions vaccinated; some days, more than 200,000 people got immunized against the virus. The fall brought a more targeted approach, with pop-up clinics in subway stations and suburban malls, to reach those who had not yet been vaccinated.

It wasn’t always smooth. And not always equitable. Yet by the beginning of December, the province was tantalizingly close to reaching its goal. On Dec. 2, 90 per cent of Ontarians over the age of 12 had received at least one dose, and newly eligible young children were lining up for their first vaccines.

But then Omicron came. And the flamingly fast-transmitting variant dramatically shifted the vaccination rules: the two-dose vaccine series is now three, and millions again need to get the shot, and swiftly.

To mark how far we’ve come — and acknowledge just how much farther we now need to go in the face of Omicron — the Star has profiled 20 of the people who helped get more than 25 million doses into our bodies.

Each said they are just one of many thousands of people who are helping and are thankful for their teams. Many admit they are exhausted, but will keep on with their vital work. They hope this winter sprint will bring a safer spring.

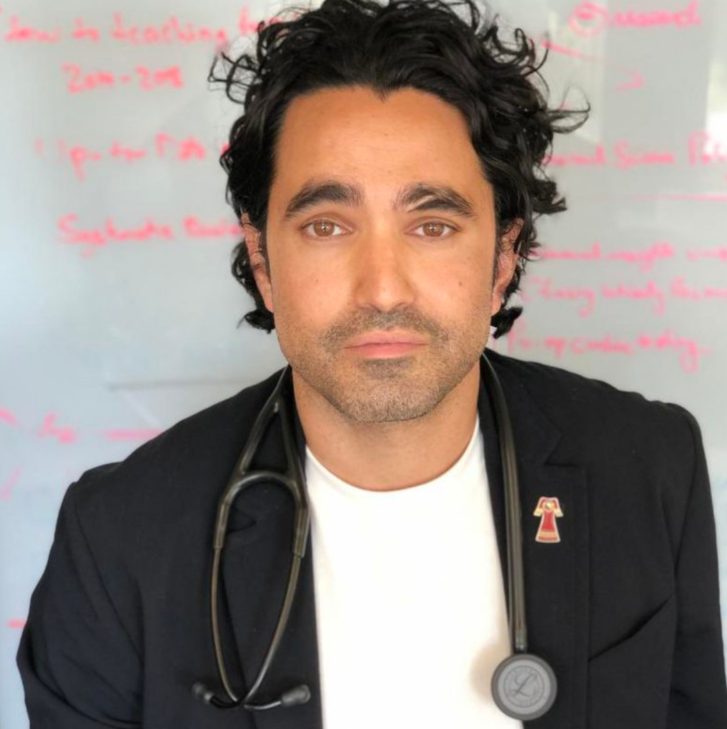

Isaac Bogoch — The infectious diseases doctor

Dr. Isaac Bogoch, a member of Ontario’s now-disbanded vaccine distribution task force, remembers a moment early in the rollout when his morale took a big hit.

It was late January 2021. Pfizer had just announced that it would be reducing shipments of its vaccine to Canada to retool its production line in Belgium to ensure it could meet increased long-term demand. And that meant Ontario would have to make do with fewer vaccines just as its rollout was starting to gain steam.

“That really stung,” recalls Bogoch, who has become a household name due to his commitment to answering any and all media requests, in addition to his day job as an infectious diseases specialist at UHN. “I know it was temporary … and we had no reason to believe that was not what was going to happen. But the public reaction to that and the reaction from many vocal pundits was extremely challenging.”

It was a time Bogoch calls a “low point.”

“You’re trying to roll out vaccines in an equitable and data-driven manner and you’ve got things that are just starting to come into shape and really take off, and then things that are so beyond your control really slow things down.”

Bogoch and his colleagues persevered and eventually helped more than 80 per cent of Ontario’s eligible population become fully vaccinated.

“It was just incredible to watch the team work, so many people working behind the scenes, so many volunteers, public health professionals, pharmacies, family physicians and organizers,” he said. “It really exemplified Ontario coming together to literally and figuratively roll up their sleeves to get the job done.”

—Kenyon Wallace

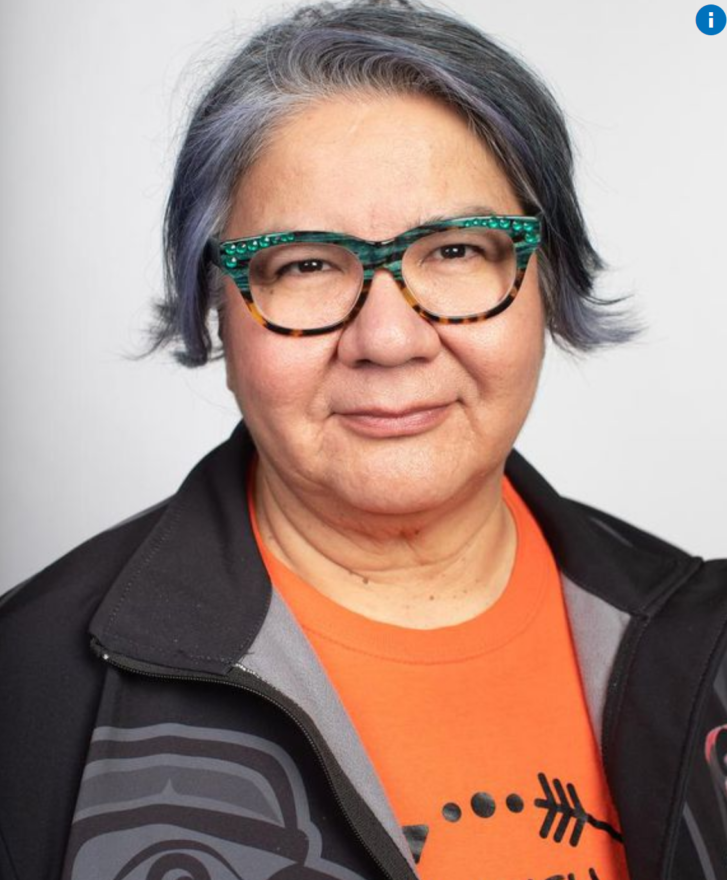

RoseAnne Archibald — The Indigenous leader

The National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, RoseAnne Archibald, was instrumental in the effort to bring vaccines safely and efficiently to on-reserve First Nations communities in Ontario.

Archibald sat on the province’s Vaccine Distribution Task Force as the then-Regional Chief of Ontario — a contribution that helped put Indigenous people’s needs front and centre at the policy table.

Archibald said she was concerned about the impact COVID-19 would have on Indigenous communities before the province announced its first lockdown in March. “We often have 20 people in one house, one bathroom,” she said. “Many communities in Ontario were under long-term water drinking advisories at that time.”

Archibald quickly called Premier Doug Ford to encourage further research and awareness on the virus. First Nations communities became some of the first to lock down.

When vaccines were on the horizon, she spoke to the premier again to ensure she could contribute. This led to Operation Remote Immunity, which brought vaccines to Indigenous communities. “That was really the beginning of being able to advocate for our people.” Archibald said.

Her leadership and advocacy, with the help of people mobilizing on the ground, helped keep infection rates low in those communities, ultimately saving lives.

—Nadine Yousif

Maria Muraca — The family doctor

In the first pandemic year, Dr. Maria Muraca, a family physician and medical director of the North York Family Health Team, did everything she could to protect her community.

She helped lead North York’s COVID-19 testing strategy with family physician Dr. Rebecca Stoller, together setting up assessment centres with North York General Hospital, where both are on staff, and making sure vulnerable populations could access tests. At the start of influenza season, they led efforts to get flu shots to the community.

So when COVID vaccines were approved, Muraca used existing contacts and infrastructure to help run North York’s vaccine response. She says her 15 years as a family physician, and leadership role with the North Toronto Ontario Health Team, ensured the strategy was team-based and community-minded.

“I knew we needed to reduce the barriers to getting vaccinated. We needed to meet people where they are at.”

Muraca will remember many moments, from seeing her primary care colleagues rush to deliver vaccines to holding the hand of a young man afraid of needles while he got his shot to setting up pop-up clinics in parks so people could get jabs while out for a summer evening walk. North York General and the North York Toronto Health Partners have administered more than 250,000 shots.

Muraca also recalls riding her bike along Bathurst St., between Wilson and Sheppard handing out flyers at shops, alerting owners and customers of the nearby vaccine clinic last summer.

“I would show them my badge and say I’m a doctor in North York. It ended up being a way for people to ask really important questions. I could make these face-to-face connections with people, and often they would later show up at one of our clinics.”

—Megan Ogilvie

Samantha Yammine — The popular scientist

Samantha Yammine is a science communicator and bright light in the muck of misinformation, who used social media to show people how vaccines work, and respond to questions.

Yammine, who has a PhD from the department of molecular genetics at the University of Toronto, is better known as “Science Sam” on Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, where her easily digestible and informative videos help bridge the gap between experts and the public.

“My goal is to make shareable content that empowers people to make a decision about vaccination,” Yammine said. “We’ve been really bad at bringing people into science and this was a time where we had an opportunity and a lot of people came and were excited to participate. That gives me so much hope.”

The “loud minority” who refuse to get vaccinated often steals the headlines. But “that doesn’t do justice to, truly, the millions of people in Toronto and across Canada, who were just so excited about it, and just wanted to learn more, and then when they did learn more, they wanted more details,” she added.

“We have some amazing parts of science that are household names, things like mRNA, epidemiology. All of these concepts are now things that people talk about at the dinner table.”

—May Warren

Anita Anand — The procurer

Anita Anand, member of Parliament for Oakville and theminister of public services and procurement during the early rollout, was instrumental in securing the vaccine supply for Canadians.

Anand, now defence minister, recalls the moment she realized there were enough vaccines to fully vaccinate every eligible Canadian, “which was at the end of July 2021, two months ahead of schedule,” she said in an email.

“We were building towards this time throughout the spring and I knew that this objective was obtainable. However, global supply chains for vaccines remained unstable and from week to week, we kept pressing our suppliers to confirm that our shipments would arrive on time,” she added.

A turning point, she said, “was our ability to bring vaccines to Canada across the border from manufacturing facilities in the United States.

“Reading my journal, I wrote excitedly at the end of July, “I am so relieved for our country: we have enough vaccines for every eligible Canadian to be double vaxxed!” I decided to visit the warehouse in Milton where the vaccines were being stored to thank everyone who had worked for months and months to get us to that point. Our stressful days, sleepless nights, and countless calls with vaccine suppliers ultimately resulted in the protection of millions of people.”

—May Warren

Homer Tien — The problem solver

There is a triumphant moment that stands out in Dr. Homer Tien’s mind from the past year as a member of Ontario’s now-disbanded vaccine distribution task force and subsequently its chair.

It was figuring out how to get tens of thousands of first and second doses of the COVID-19 vaccine to Indigenous communities — many of them fly-in only — in a three-month time frame before spring flooding forced the evacuation of many areas.

“It was actually quite daunting,” said Tien, a trauma surgeon at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre who replaced retired Gen. Rick Hillier as head of the task force at the beginning of April.

Tien, who spent 25 years as an armed forces medical officer, recalls an exchange with Hiller when he was tasked with delivering shots to the North. “He sort of jokingly said to me, ‘Remember, you’re in charge. So you’re the one throat to choke.’ … it was that moment where I thought, ‘Oh man, I’d better figure this out.’ ”

Operation Remote Immunity was born. Leveraging his other role as CEO of Ornge Air Ambulance, and partnering with the Nishnawbe Aski Nation and Indigenous leaders, Tien oversaw a massive operation beginning in February to supply 31 northern communities and Moosonee. Aided by Ornge pilots and staff, and northern community members, they achieved the feat of administering 25,000 doses by April 6.

Indigenous communities said “never before did they feel like they were first in line to get something from the medical system that was good … That was certainly a very good moment for me.”

—Kenyon Wallace

Kyro Maseh — The pharmacist

Vaccinating Toronto residents, Kyro Maseh and his team at the Lawlor Pharmacy in the Beaches neighbourhood decided to mark daily milestones in a big, loud way.

Maseh became known as the bell-ringing pharmacist, who would ring a bell and yell “shots in the arm!” While his staff would respond, like a scout chant, “COVID’s gone!”

He also threw a major bash for the 1,000th shot the pharmacy administered near the end of April, full of confetti and music.

“I try to make a point in my day-to-day, in my practice, to always reassure people who receive health care, have an enjoyable experience in the process, and do my best to lift up their spirits,” he said.

“They are already facing a challenge, and the important thing for me is to ensure, even just for a few moments, they can forget about the tribulations they are facing by something silly like ringing a bell, or wearing a Santa Claus hat,” he added.

Ensuring that his patients “feel human” has been a part of his work since he became a pharmacist, he said.

“And with the help of my neighbours and community volunteers, I feel that over this pandemic we’ve done a good job. We hope that we can continue to do that.”

—Olivia Bowden

Mohamad Fakih — The entrepreneur

As the CEO of Paramount Fine Foods, Mohamad Fakih has become known for his connection and commitment to the community his restaurant business exists in.

Even though his chain of Lebanese restaurants has suffered during the pandemic, Fakih remained dedicated to giving back, beyond charitable endeavours including Islamic Relief Worldwide and SickKids, and help for refugees.

He became outspoken on the importance of the vaccine. Paramount donated meals this summer to honour Peel Region staff who worked in clinics. Perhaps fittingly, the Paramount Fine Foods Centre sports and entertainment facility in Mississauga (Paramount owns the naming rights) became the site of a mass vaccination clinic, and youth-focused campaigns.

One of many major challenges this year was combating misinformation around the vaccine — and seeing his teenaged son, Karim, be the target of vitriol for encouraging young people to get vaccinated, said Fakih.

“I always say making a difference comes with pain. If you want to make a real difference, you do it until it hurts,” he said. “And it’s one thing about people attacking me, but my son is on video to encourage children to get vaccinated so we can send them back to school, and their normal life. That was a difficult moment.”

“But the good part of it … Karim didn’t care. All he cared about was going back to his friends, and if that’s what it takes to keep everyone safe … our children get it and the majority of Canadians get it.”

—Olivia Bowden

Tali Bogler — The voice for pregnant patients

Last winter, after Canadian health officials released initial guidance on who was eligible for COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Tali Bogler knew she would need to advocate for her pregnant patients.

As chair of family medicine obstetrics at St. Michael’s Hospital, Bogler was alarmed that pregnant individuals — especially essential workers and health-care providers who could not stay safe at home — were at first excluded from getting the shot.

Bogler immediately pushed for pregnant people to have access, raising her concerns at the provincial level, in the local hospital system and on social media, where she has a prominent voice as co-founder of the Instagram account Pandemic Pregnancy Guide (PPG).

“I just felt I had to do what was best for my patients,” she said, noting evidence quickly accumulated that COVID vaccines are safe and effective in pregnancy. “They are a vulnerable group and I wanted to do whatever was in my power to ensure they were better protected.”

In April, the province prioritized pregnant individuals for vaccines after an alarming number of pregnant patients were in hospital critically ill with the virus.

Since then, Bogler has continued to speak up for pregnant people and uses PPG to provide evidence-based advice on why COVID vaccines are vital during pregnancy. With Omicron surging and only about 70 per cent of pregnant people in Ontario having received two doses, Bogler has no plans to stop.

“When someone comes up to me at a mass vaccination clinic because they recognize me, and says ‘Thank you. I’m here because of you,’ that is the most meaningful to me. That is what keeps me going.”

—Megan Ogilvie

Jaskaran Sandhu — The Sikh community advocate

Jaskaran Sandhu worked with the World Sikh Organization of Canada to launch a vaccine clinic inside one of the largest Sikh places of worship in North America.

Sandhu’s efforts in the Ontario Khalsa Darbar gurdwara in Mississauga, near the Brampton border, were born out of a desire to help protect a region with some of the highest COVID rates in the province. They were also born out of frustration.

While his community battled stubbornly high rates of infection, Sandhu noticed many critics were maligning Brampton and blaming its residents. Meanwhile, targeted help from public officials was slow to come.

“At that point, there was research suggesting that a lot of the transmission that was happening was actually workplace-related,” Sandhu said. “What was missing from the dialogue was the reality that this city is made up of blue-collar workers that were at the front lines facing the brunt of COVID-19.

“That nuance, that empathy, was missing.”

Bringing the vaccines directly to the community through the place of worship made a big difference. Gurdwaras, Sandhu said, are where Sikhs mark the important milestones, like births, deaths and weddings. In 2021, it was where they were able to get a life-saving vaccine, too.

“It was incredibly special to people.”

—Nadine Yousif

Vivian Stamatopoulos — The seniors advocate

Long before the province announced a vaccine mandate for staff, support workers and volunteers at long-term-care facilities in October, Vivian Stamatopoulos joined workers on the front lines of Ontario’s nursing home crisis calling loudly the measure. She marched in protests, even organizing one, and raised alarm bells that the virus was getting into facilities through an obvious route: employees.

So it’s understandable why the tenacious family caregiver advocate was devastated when Ontario’s first vaccine mandates for certain workers didn’t include the long-term-care sector.

“I was livid,” said Stamatopoulos, who also juggles full-time teaching duties as a criminology and social justice professor at Ontario Tech University when she isn’t helping families. “When the Delta variant arrived, and we continued to see cases in homes, it only made sense that it was getting in through the staff.”

When the first vaccine mandates in the summer didn’t include long-term-care workers, Stamatopoulos says she “made it her mission” to “hit this government as hard as I could to put that vaccine mandate into place, because I knew it was the missing link.”

Indeed, seldom a TV, radio or social media post went by without Stamatopoulos calling for mandatory vaccinations for long-term-care workers, or lamenting problems experienced by residents trying to access the vaccine.

Stamatopoulos experienced a vindication of sorts when Long-Term Care Minister Rod Phillips, in making the vaccine mandate announcement, noted that unvaccinated staff were a “significant cause” of outbreaks in the homes.

“It was nice to see that, because the families I work with were not going to rest until that gap was rectified.”

—Kenyon Wallace

Angela Carter — The community leader

Brampton was inundated with COVID-19 cases during the spring third wave. A large temporary workforce that didn’t have sick-day access, along with mistrust of a health-care system that has caused harm, meant that targeted interventions were needed to get residents vaccinated.

Angela Carter, the executive director of Roots Community Services, partnered the organization with Peel Region to launch a vaccination clinic specifically meant to make Black residents feel comfortable. The clinic featured Black staff, including vaccinators.

She credits her team’s hard work for the clinic’s success, because of its outreach before the launch. Now, they have continued weekly meetings with Peel Region to talk about engagement.

Seeing Black residents come to the clinic “and feeling good, that there are others who look like them that were doing the work, that make them feel comfortable … those were hopeful periods for me,” she said.

Carter said she and her team had to work hard to convince governments to prioritize Peel.

“Certain levels of government … they did not really understand the complexities of communities. They didn’t understand you can’t have a blanket approach,” said Carter. “Being able to be at the table to say ‘that’s not going to work’… and they listened. The challenge was being there and making sure your voice was heard.”

—Olivia Bowden

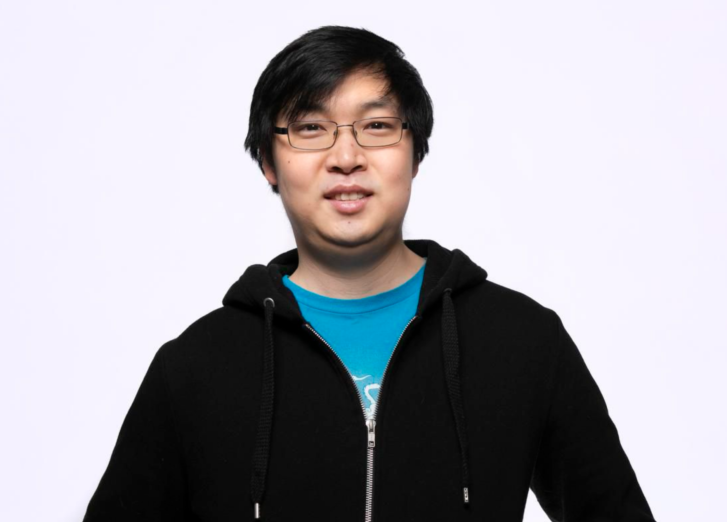

Andrew Young — The Vaccine Hunter

Many people in Ontario — and across Canada — would probably credit Vaccine Hunters and the man behind them, Andrew Young, for pointing them in the right direction to where and how they could get vaccinated.

Young, who works as a web developer at the soon-to-be-renamed Ryerson University, said the Twitter account, which amassed over 250,000 followers, was born from computer scripts he wrote to find vaccine appointments for his parents.

Young realized others needed similar help, and Vaccine Hunters was born. People jumped on board, with the network at its height growing to 104 volunteers. Folks like Toronto-based Talia Pankewycz monitored social media accounts and provided answers to people in real time. Others, like Carleton University second-year student Eric Herscovich, worked behind the scenes to develop an accessible vaccine finder tool.

Their efforts were particularly appreciated at a time when the provincial rollout was criticized as disorganized and inaccessible.

“I’m so grateful to have met the volunteers, mostly virtually,” Young said. “We shared such a strong bond in wanting to help.”

The network continues to help, especially with the rollout of third doses. They also have their sights on global vaccine equity, and were recently consulted by the World Health Organization to help countries outside Canada with their own rollouts.

—Nadine Yousif

Sabina Vohra-Miller — The misinformation fighter

Long before the pandemic, Sabina Vohra-Miller was an active member of various social media sites trying to correct misinformation about vaccines. So when COVID-19 hit, Vohra-Miller, who has an MSc in pharmacology and is pursuing a doctorate in public health, was well practised in reaching out to concerned parents and communicating the benefits of vaccination.

But while her efforts on Facebook were met with gratitude by many, volumes of anonymous hate mail prompted her to take another tack. And in July 2020, her website Unambiguous Science was born.

“The idea was that I would make the science unambiguous but keep me ambiguous and anonymous,” Vohra-Miller explained. “The problem is that sort of didn’t work in the long run because people started to put two and two together.”

Since then, Unambiguous Science has become a go-to resource for objective, dispassionate and easy-to-understand information on everything COVID, from vaccinations, testing and masks, to definitions, mythbusting and variants. She creates helpful infographics on complicated concepts. That’s in addition to vaccine education sessions she conducts with community health centres to address hesitancy and just answer questions. And it’s all on her own time.

Vohra-Miller recalls one education session she conducted when uptake was around 50 per cent of staff at a health centre. After her session, uptake shot up to 90 per cent. Then, after she spoke one-on-one to several individuals, uptake rose to 100 per cent.

“That was a time when I thought, this is worth it,” she said. “The sacrifices I’ve put forward, my family, with my child not seeing me as much, mental and physical health and all the hate messages. At that point it just solidified that this was all worth it because this is saving lives.”

—Kenyon Wallace

Phil Anthony — The deliverer

When Phil Anthony arrived at the first community vaccine pop-up, in the parking lot of the Masjid Darus Salaam mosque, across from Iqbal Halal Foods in Thorncliffe Park, he couldn’t believe what he was seeing.

“I got there at five o’clock in the morning. There were already a thousand people lined up, and we were supposed to start at nine,” he recalls.

Anthony, a nurse by training, is co-chair of the city’s Vaccine Equity Strategy, and manager of the East Toronto Mobile Vaccination Strategy at Michael Garron Hospital. He and his team ramped up the rollout by delivering shots to where people lived.

“It was in that moment right there that I realized that, bringing the vaccines to the people, working with our community partners, was going to be the only way that we were going to make this campaign successful,” he said.

“The turnout was overwhelming, the positivity around the event was overwhelming, and it’s that event alone that shifted the entire strategy of the city.”

The team went on to give “vaccines anywhere from mosques, to basketball courts, to community centres,” he remembers.

“That was the moment that gave me hope that there were better ways to deliver vaccines to people, to take an equitable health approach with it, and you really use the community as the local experts.”

—May Warren

Rev. Maggie Helwig — The community advocate

The Reverend Maggie Helwig at Church of Saint Stephen-in-the-Fields, in the heart of Toronto’s Kensington Market, helped many of the community’s most marginalized and those without stable housing get timely access to vaccines.

Helwig began the work at the Anglican church long before the first inoculation efforts were underway. As a first step to build trust early on, she and others talked about vaccines informally with the people they help every day.

“This is a population that has suffered a lot of institutional abuse,” Helwig said. “There’s a high degree of mistrust of the medical system, there’s multiple layers of trauma.”

When vaccines first became available, clear barriers to access emerged. Most people were booking appointments online from the comfort of their homes, but those living in group or rooming homes had no access to a computer or phone.

To help, Helwig’s church set up a registration booth for people, and even drove some folks to their appointments. They later set up a vaccine clinic in the area with the help of St. Stephen’s community house.

Helwig stressed these efforts were made possible by dozens of volunteers who banded together to make the vaccine as accessible as possible. “I am just one person in a huge team of people who have been working on this.”

—Nadine Yousif

Glyn Boatswain — The hospital leader

Scarborough has been a COVID-19 hot spot throughout the pandemic, with accessibility to testing sites a major issue for residents who rely on public transit. Glyn Boatswain and her team at Scarborough Health Network launched pop-up assessment centres all over the region in spring 2020 to tackle the issue.

And when it came to the vaccination rollout — Boatswain, the hospital’s chief nursing executive — her team’s work stood out again.

The hospital’s Scarborough Vaccine Team staff at their clinic at Centennial College marked a milestone in July, with the highest daily average of doses administered by a community clinic. At that point, they were vaccinating 1,497 residents a day.

“In Scarborough, there was a bit of lack of confidence of how truly effective the vaccines were, and how we could engage our community that the vaccine is safe, and it’s the best thing out there,” she said.

“It was a bit of a journey and took a lot of hard work … but in the end it really worked out for us,” she said. Hospitalizations were down in Scarborough in the fall, which was a direct result of vaccinations, she said.

“You have to step back for a minute, at how humbling it is … some great work was really done here. And that still is very rewarding.”

—Olivia Bowden

Andrew Boozary — The front-line equity advocate

Dr. Andrew Boozary is a family doctor, executive director of the Gattuso Centre for Social Medicine at the University Health Network, advocate, and one of the co-leads on the COVID-19 homelessness response for the Toronto region.

A front-line vaccinator at community clinics, he has also been a clear voice calling for equity in the vaccine rollout across the GTA, and for the neighbourhoods hardest hit by COVID to get access to shots.

“There was this notion that was put out there that certain communities wouldn’t want the vaccine,” he said. “We saw vaccines in neighbourhoods that had the lowest COVID positivity rates, and a dearth of vaccines for communities that were still on fire, positivity rates that were nearing 20 per cent or higher.”

This was “one of the most damning disparities I’ve ever seen in my career,” he added, akin to “sending fire trucks to where the fires aren’t.”

He recalls a spring vaccine pop-up on Tobermory Drive, near Jane and Finch, as one of the year’s most hopeful moments. “That first weekend — there were people saying, you know, people may not come — but that notion was obliterated that weekend.

“Cheryl Prescod and I, who is the head of the Black Creek Community Health Centre, we couldn’t believe what we were hearing as to how long these lines were.” The two got into her car and “had to just keep driving” to reach the end.

“That for me was just so moving to see, all of these people and families and essential workers, doing everything they could amidst all of the other policy obstacles.”

—May Warren

Luwam Ogbaselassie — The Community Co-ordinator

On a Sunday afternoon, just days before Christmas, Luwam Ogbaselassie was at a vaccine clinic at the Jamaican Canadian Association Centre in North York, busy providing the key supports to help get hundreds of residents their COVID vaccines, from kids needing first doses to adults lining up for boosters.

As implementation lead with UHN’s Social Medicine Program, Ogbaselassie works closely with community partners to support vaccine efforts, primarily in Toronto’s Black Creek and Humber River neighbourhoods, hard hit by COVID. The team brings the vaccines, clinical staff and technical requirements to clinics, shelters and congregate living centres.

At the recent Sunday clinic, Ogbaselassie and the team, including members of the Black Physicians Association of Ontario, and staff from Black Creek Community Health Centre and Caribbean African Canadian Social Services, offered additional health and social supports to residents, including blood pressure monitoring and providing food baskets.

“The clinic is focused on the Black population and we’re ensuring the clinic is well-represented in its staffing,” she said. “This increases the level of trust and engagement from the community, to come into the clinics where they see themselves represented.”

Ogbaselassie, who also supports those working to vaccinate the underhoused and unhoused in the city’s midwest region, says a team-based approach that listens and responds to the needs of individual communities is vital to their work. So far, UHN’s Social Medicine team has provided more than 2,500 doses in the shelter system and more than 50,000 doses in Toronto’s northwest corner.

—Megan Ogilvie

Tara Kiran — The family doctor

As a family physician at St. Michael’s Hospital, Dr. Tara Kiran knew she would one day help vaccinate her own patients against COVID-19.

But even before vaccines arrived in Canada, Kiran also knew she could play a larger role, as vice-chair of quality and innovation at the University of Toronto’s Department of Family and Community Medicine.

With U of T colleagues, Kiran created interactive online modules for primary care physicians — accessible to anyone — to provide guidance on the vaccines, from the safety of mRNA vaccines to how to help patients feel confident.

Kiran put aside her other academic work to produce the modules, which she calls a “one-stop way for people to learn” to help bring emerging evidence to the doctor’s office.

Throughout the pandemic, Kiran has co-led bi-weekly webinars for primary care physicians covering top-of-mind COVID issues. Since vaccines were approved, 600 to 900 family doctors regularly join the webinars, many telling Kiran they provide a place to review the latest evidence and a sense of community during a challenging time.

“The notes I get telling me it’s made a difference make my day,” says Kiran, who has also used her platform to push for a more equitable pandemic response.

This year, the Star profiled Kiran’s efforts to help hesitant patients feel more confident. The story followed a mother and daughter as they consulted Kiran on whether to get vaccinated.

“We think of anti-vaxxers as an extreme group. But there are so many people who come from humble circumstances who’ve been struggling with the decision about their vaccines. I think (the story) helped people to empathize and better understand what people are going through when they’re not sure about a vaccine.”

—Megan Ogilvie

Article From: The Star

Authors: Megan Ogilvie, Kenyon Wallace, May Warren, Nadine Yousif and Olivia Bowden