‘Even if you realize you need help — it’s very difficult to find it’: psychologist

The mental health of Canadians has deteriorated in the two years since the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, putting massive pressure on a mental health-care system that was already close to a breaking point.

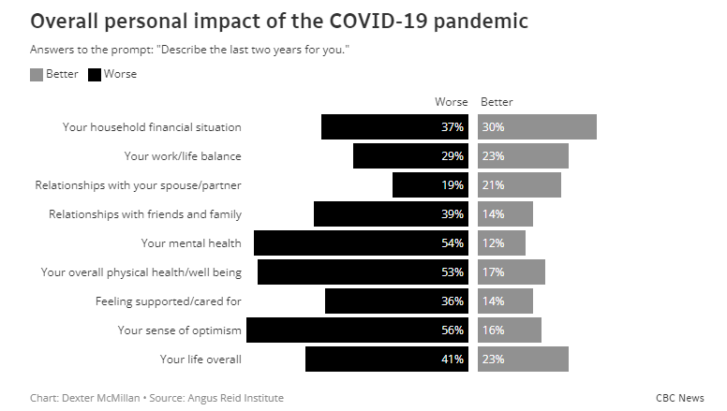

In a new survey conducted by the Angus Reid Institute in partnership with CBC, 54 per cent of Canadians said their mental health had worsened during the past two years — with women faring significantly worse than men.

Sixty per cent of women aged 18 to 34 said their mental health had worsened throughout the pandemic, and that number jumped to 63 per cent for women aged 35 to 54 over the past two years.

The survey coincides with new research from the Canadian Mental Health Association and the University of British Columbia (UBC) that paints a stark picture across the country of a mental health crisis growing in the shadows of COVID-19.

Many Canadians are stressed about what could come next in the pandemic — with 64 per cent responding they were worried about the emergence of new coronavirus variants in the future, which could jeopardize plans to live with the virus as public health measures lift.

Fifty-seven per cent of respondents felt that COVID-19 will be circulating in the population for years to come, while researchers found two years of pandemic-related stress, grief and trauma could lead to long-term mental health implications for some Canadians.

“After two years, Canadians are really feeling overwhelmed and exhausted,” said Margaret Eaton, national CEO of the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA).

“There is an epidemic of chronic stress that’s been going on for so long, and people are feeling so much uncertainty, that we’re concerned now that it will take much time for them to get over this experience of the pandemic.”

The situation is similarly dire from a global perspective, with new research from the World Health Organization finding that the first year of the pandemic increased worldwide levels of anxiety and depression by an astonishing 25 per cent.

“The information we have now about the impact of COVID-19 on the world’s mental health is just the tip of the iceberg,” WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said.

“This is a wake-up call to all countries to pay more attention to mental health and do a better job of supporting their populations’ mental health.”

‘System has long been broken’

Canada’s mental health-care system has operated for decades as a partially privatized, fragmented system of hospitals, psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists and community groups paid for either through donations, government funding or directly out of pocket.

“We live in this patchwork quilt system of mental health where some people, if you have a good employer with a benefits plan, then you might get some psychotherapy,” Eaton said.

“But a lot of people have suffered through the pandemic and haven’t found any support …. Many are finding that they have to get on a wait-list in order to see a psychotherapist or get into a counselling program and that has been very hard on Canadians.”

Dr. Peter Liu, a clinical psychologist in Ottawa, said the system is unable to keep up with the mental health-care needs that have grown dramatically in the pandemic, and isn’t sure how the industry will be able to fill the gaps in the future.

“The demand for services has increased to levels I’ve never seen before and psychologists that I work with and collaborate with are all saying the same thing,” he said.

“It’s actually too much for what psychologists can meet …. Even if you realize you need help — it’s very difficult to find it.”

Emily Jenkins, a co-researcher on the survey and associate professor of nursing at UBC, said while Canada has seen significant mental health challenges at the population level over the past two years, the pressure on the mental health-care system pre-dates COVID-19.

“People can wait for a long time, and their mental health has to be at such a critical point to be able to access those acute care services — that’s really not providing care when needed,” she said.

“The system has long been broken.”

Breaking down barriers to access

Eaton said Canada is at a crucial “moment in time” for mental health that she said calls for the complete restructuring of the mental health-care system — rather than “just throwing money” at it.

The federal government has pledged $4.5 billion through health transfers to provinces and territories over five years for targeted funding for mental health, something Eaton said could be a “potential game changer” if the funding is used to expand treatment availability.

Federal Minister of Mental Health and Addictions and Associate Minister of Health Carolyn Bennett said Canada has also launched resources to help Canadians access support like Wellness Together Canada and the PocketWell app — but they are largely conduits to care.

“The old-fashioned way of siloed thinking has not been serving Canadians,” Bennett said.

“I think COVID has taught people that they can ask for help, they’re not alone, and that they need to be able to let people know that they’re struggling and that care is going to be a bit different than it was before.”

Eaton said funding needs to go toward early mental health interventions in communities across the country to ensure vulnerable populations receive adequate, timely support — something she said is “not being taken care of in the system right now.”

“We would also like to see funding for psychotherapy and psychology, that should just be a basic service,” she said.

“And ultimately what that wraps into is the notion that we all need universal mental health care — that health care should include mental health.”

Eaton said as Canadians recover from the pandemic, funding from the federal and provincial governments needs to do more to address systemic problems and break down barriers to access to avoid a breaking point.

“Our concern is that the longer-term impact is where we’ll really need to invest,” Eaton said.

“Even though we might be getting back to work and to school, things are sort of normal — we expect it can take up to two years before we’ve dealt with the longer-term impacts of COVID and this chronic stress.”

‘We’re going to bounce back’

The level of stress and anxiety many Canadians have been under throughout the pandemic can also have long-term implications on the brain that threaten to jeopardize our ability to bounce back in the future.

“When people are feeling unsafe for very long periods, that has a real cumulative deterioration of their functioning,” Liu said. “Stress is only magnified with time when you’re in this kind of state.”

Liu said this constant stress can also lead to the suppression of the immune system, sleep disruptions, anxiety, depression and emotional dysregulation.

Liu said reducing work stress, withdrawing from toxic people in your life, building up connections with healthy relationships and seeking support whenever possible could maintain functioning, prevent sliding further into burnout and fend off additional stress.

“Unfortunately, the pandemic has made it really hard for a lot of people to connect with others,” he said.

“But working on increasing contact, communication, and nurturing of relationships will definitely help everyone because the strength of attachment from relationships, it develops in a person a sense of safety and security and even confidence.”

Liu said the silver lining is that people are resilient by nature and the brain is built to adapt to a wide range of stressful experiences.

“The brain can cope with just about anything that life throws at it,” he said.

“So I would say, long-term, we’re going to bounce back. There is going to be a collective as well as individual resilience. Unfortunately, the path to get there is a very, very bumpy one and very stressful.”

Article From: CBC news

Author: Adam Miller