Systemic racism left a paper trail. A century later, researchers are hunting for the evidence.

Every Remembrance Day, Cecil Yip would shine his shoes and polish his medals. Then, putting them on with his purple beret and navy suit jacket, he’d set off for Vancouver’s Chinatown. He’d meet his brother Dick and other veterans of Pacific Unit 280 to march in the big parade, sometimes with tears in his eyes, and after, raise a glass to their fallen comrades.

Yip did this every year until his death in 1989.

His dedication made an impression on his daughter Linda Yip. But when she asked him about what it was like taking part in the Second World War, he’d shake his head.

“He was angry, he was frustrated,” recalled Linda. “He’d say, ‘You don’t even know what you’re asking.’ As a child, it was a taboo subject you just didn’t bring up. But it had emotional impact, even though you had no idea why.”

She only had more questions. One day, while rummaging through his desk, she found an odd card in one of the drawers.The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

Her father’s baby picture was on it, along with his Chinese name. But while it looked like a birth certificate, it came from the Department of Immigration and Colonization’s Chinese Immigration Service.

Strange, because her father wasn’t an immigrant. He was born in Canada.

The certificate had a number in the top right corner. It stated that her father had been “registered as required.” At the very bottom it read, “This certificate does not establish legal status in Canada.”

When she asked her father about it, he scolded her for going through his things and didn’t say anything else.

It would be years before Linda learned what the document was: one of many pieces of identification from a time when the Canadian government required all Chinese to be registered, numbered, interrogated and tracked.

Racial profiling and border control in the late-1800s and early-1900s wasn’t done by computers or through facial recognition tech, but what the government did use to target Chinese people was considered cutting edge at the time — for example, certificates with photo ID. And as late as 1950, border officials used X-rays on young Chinese as a way of ensuring they weren’t cheating the age limits for family reunification programs.

And there was the paperwork. Systemic racism, as it turned out, required a lot of paperwork.

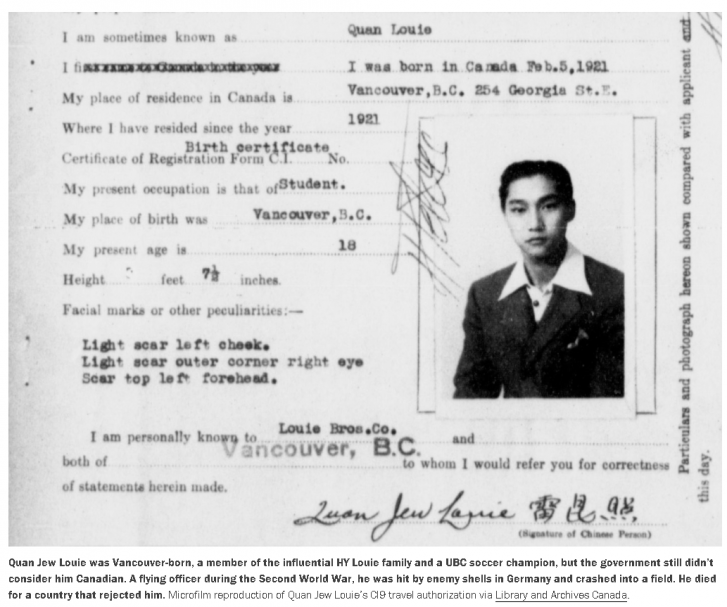

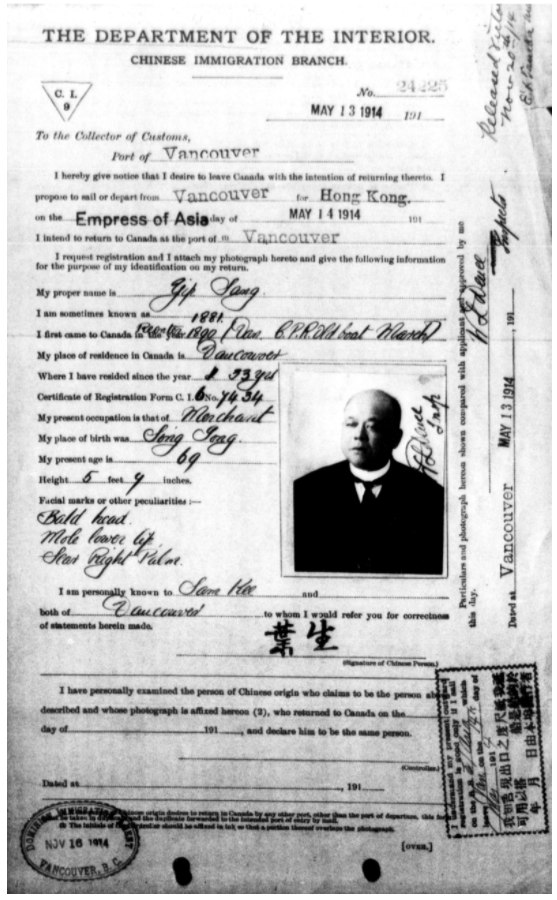

Chinese immigration certificates were the government’s way to monitor and contain the Chinese people who remained in Canada after the transcontinental railway was completed in 1885. There were different certificates for different purposes, from ID to travel authorizations. Each was known by a “C.I.” code in the header.

Library and Archives Canada has immigration case files with details of certificates, but they are not public due to strict privacy policies.

As for certificates themselves, some are in public archives, but the majority have likely been lost or thrown out, perhaps unknowingly by descendants or purposefully by bearers who’d rather forget the past. Upon gaining citizenship, some Chinese Canadians burned the discriminatory papers that for years held a tight grip on their lives.

Of certificates that do remain, Catherine Clement and a team of volunteers are hunting them down.

Like Linda, Clement came across these documents by chance. A decade ago, she was interviewing veterans as the curator of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum. “They’d tell me stories, we’d look through albums and their little shoeboxes, and I kept on finding this card,” said Clement.

Why would these Canadian-born people, veterans no less, have documentation to confirm their non-status in Canada?

A code on the top-left corner of the cards offered a clue: C.I.45. These were issued when Canada shut the door to Chinese immigration in 1923. Those of Chinese heritage who remained were required to register as part of a mass, nationwide drive.

“Everyone was going to get scooped up,” said Clement. “There were posters everywhere in English and Chinese about what you had to do. It wasn’t just ‘Show us your certificate and we’ll stamp it.’ You had to prove who you were and justify what you had been doing. There was a whole series of questions: where did you work in your first year, where did you work in your second year, who was your boss… they were very detailed. Failure to do this meant a $500 fine, imprisonment or being shipped out of the country. It scared everybody.”

Immigrant or not, those who passed registration were issued a C.I.45 by the immigration department.

“If you were born in Canada, whether you were Italian or Irish, you were a British naturalized citizen. And yet for the Chinese, their children, the first generation born here, they were given these cards,” said Clement.

She remembers one veteran’s reaction when showing her the C.I.45.

“He was so angry and red-faced. ‘They gave this to our parents. Can you imagine what our parents felt?’ There are so many different ways the government could have registered Canadian-born children. But they chose to send them a signal by giving them an immigration card.”

It was legislation that turned Canadian-borns into perpetual foreigners and second-class residents.

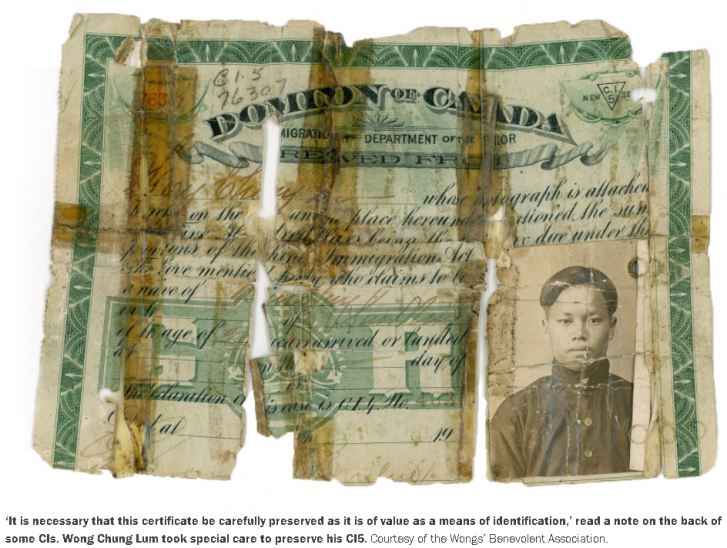

The C.I.45 was by no means the first of these certificates. The earliest was the C.I.5 in 1885, used to register immigrant Chinese people and indicate whether they paid the head tax to enter Canada.

The certificates grew more complex over time, with colour-coding and details noted like facial peculiarities, each change designed to enforce the tightening restrictions around Chinese people in Canada.

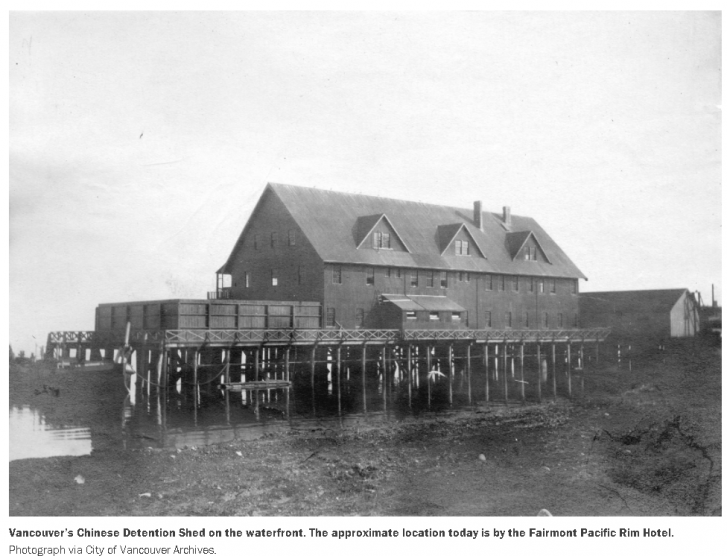

In 1910, the C.I.9 was required of all Chinese who wanted to leave the country and was only valid for travel within a limited time. Photos were required, making the C.I.9 the first-ever mass use of picture ID in Canada. Chinese people were processed, and some detained upon re-entry, in jail-like sheds.

The C.I.30 was for more well-to-do immigrants like merchants, diplomats and scholars, who were exempt from the head tax.

And there were other certificates. One for Chinese crew members coming ashore. Updated versions with photos, to make identification easier for immigration officials. And so on.

“This was over-documentation, over-surveillance, over-control, and incredible intimidation. Everything you do, there’s a certificate,” said Clement. “Even Americans, who had an exclusion act earlier than us, were not as draconian in how Canada applied its rules.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act, officially known as the Chinese Immigration Act, came into effect on July 1, 1923. Chinese immigration was essentially banned, with only 15 privileged individuals admitted during the act’s 24-year span.

Rather than Dominion Day or Canada Day, the Chinese knew July 1 as Humiliation Day. In some cities, they lowered flags to half-mast and hung mourning wreaths on doors and in shop windows.

With the 100th anniversary of the act coming up, Clement and her team have launched a project called “The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act.”

The team is looking for families with C.I. certificates in their possession. The C.I.s will be scanned and displayed as part of an exhibition, and later collected into an archive.

Clement is the curator, and the project is being funded by the Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society, the University of British Columbia’s Centre for Community Engaged Learning and the British Columbia Historical Federation.

The story of Canada’s Chinese head taxes is well-known, but less so the system of control around the C.I.s, and the despair brought on by the Exclusion Act in the 24 years before it was repealed, said Clement.

Along with the scans of the C.I.s, the Paper Trail team is hoping that families will be able to share stories behind the certificates.

The certificates were extremely important, because Chinese people were only issued a single copy and losing it meant interrogation by immigration officials for hours. Those who qualified for a replacement — the C.I.28 — were required to pay $225. It was a stiff fee, considering that it was half of the $500 head tax at its maximum, amounting to a year’s wages for a typical labourer.

Some of the scans in the Paper Trail collection show how C.I.s were folded and kept on one’s person. “In any moment he might be stopped to show his papers,” said Clement. Those that became tattered were taped together by their bearer, heeding the note on the back that they “be carefully preserved.”

Popular hatred of the Chinese was fuelled by the press and politicians. A 1922 headline in the Victoria Times daily newspaper declared that Chinese had to be kept out in order to “Save B.C. for White Race.” MP George Thomas McBride worried that if “the influx of Orientals was not checked, the white race would have to retreat over the Rockies.”

Other immigrant groups were not immune to racism, but none experienced the bureaucratic force that the Chinese did, said Clement. Historian Lisa Rose Mar described these decades of navigating the maze of documentation as “Kafkaesque.”

The valuable nature of these C.I. certificates meant that some Chinese people would use them to get loans from merchants. The merchant would keep the certificate as collateral, and the borrower would get it back once they paid off their loan.

Some Chinese in Canada even sold their certificates to immigrant hopefuls in China so that they could enter using a false identity. This is where the terms “paper son” and “paper daughter” came from, with immigrants posing as relatives of others using the C.I. they purchased.

It also led to intense fear among the undocumented. The Paper Trail team looked through old issues of the Chinese Times newspaper around the time the Exclusion Act was in effect. Loved ones would purchase space in the publication concerning friends and family who disappeared or died by suicide.

This was likely an intent of the government with the Exclusion Act, said Clement: registering and keeping track of as many Chinese people as possible, and hoping that the others would go away.

The exclusion skewed the demographics of Chinese in Canada even further. There was a class divide, because merchants had brought their wives over, while labourers couldn’t afford to. Many who were considered bachelors were in fact married to wives overseas. Any hope they had of saving enough money to reunite in Canada was quashed by the immigration ban. Coming to Canada in the first place was already an expensive gamble, leaving them with no means to return home.

“You can just imagine the despair,” said Clement. “We will never hear those stories, because most of them were single men who died alone.”

Between 1921 and 1941, the census shows the population of Chinese males dropping from 21,800 to 16,400.

Linda Yip, now in her mid-50s, has become a professional genealogist, carried by her childhood curiosity of family history. She has a special lens to view what the first generations of Chinese experienced in Canada, because her great-grandfather was one of the most famous people in Vancouver’s Chinatown, Yip Sang.

But even his prominence and status as a naturalized British subject couldn’t save him from the scrutiny of his papers at border checks.

Yip Sang left Guangdong for San Francisco in 1864, where he worked as a dishwasher, cook, cigar maker and a labourer in the goldfields. He followed the gold trail into Canada, eventually settling in Vancouver, where he peddled sacks of coal door to door. He then found work with the Canadian Pacific Railroad Supply Co., where he worked as a bookkeeper and a paymaster before becoming a superintendent of Chinese workers.

Yip Sang went on to start the Wing Sang Co., which sourced labour, produce and Asian goods. He held an impressive real estate portfolio and was heavily involved in the community, establishing the Chinese Benevolent Association and the hospital that would later become Mount Saint Joseph.

He also became a lifetime governor of the Vancouver General Hospital. He had four wives and 23 children.

Linda knew her great-grandfather’s rags-to-riches story, but other than that, just “bits and pieces.”

In her research, she found that the Chinese Immigration Service kept record of him and his movements over the years, a standard practice. One entry showed his arrival in Victoria in 1914 but mentioned that he wasn’t “released” until four days later.

“He was held in the shed,” said Linda.

Officially, they were called “Chinese detention sheds,” but those detained called them “pig pens.” Vancouver had one too, on its waterfront.

Yip Sang, for all his wealth, was still subject to the same scrutiny as other Chinese as his papers were processed and fact checked. It was ironic, because the immigration department was actually a paying customer of his company, which for two decades provided meals for detainees of Chinese detention sheds in Vancouver.

“If Yip Sang himself could not bypass the structures, then who could?” said Linda. “To me, that means nobody.”

It was because of discrimination like this that Canadian-born Chinese wanted to fight in the world wars to prove that they were worthy of rights. The government was aware of this and reluctant to admit Chinese volunteers. Among Chinese themselves, there was disagreement about whether this was a good strategy, some wanting full rights before going to fight.

The need for soldiers meant that Linda’s father Cecil and Uncle Dick were eventually called up. Uncle Dick was loaned to British Intelligence and tasked with assisting resistance movements against the Japanese in Southeast Asia, a rare combination of spy and commando soldier.

The Chinese Canadian contribution to the war effort played a role in bringing an official end to the exclusion era in 1947 after 24 years.

But the act had lasting effects, even in family stories that seemed light-hearted at first. Linda’s mother told her about growing up in Vancouver in the 1950s, with boys from Chinatowns across North America showing up at her door to ask her out.

“I thought she was exaggerating,” said Linda. “That’s not to say she wasn’t an attractive young woman, which she totally was, but it was also because the borders had been closed. The ratio of Chinese men to Chinese women was 10 to one.”

1947 was also not an end to systemic discrimination. Chinese fought to enter certain professions, especially those with strict associations. Those wanting to buy property discovered some homes had “no Oriental” covenants. Linda’s Uncle Gibb, who wanted to buy a house on Vancouver’s west side, was only able to after asking all of the neighbours for permission.

It was no wonder that Canadian-borns like Linda’s father were pained about the past and their relationships to the pieces of paper that shaped their lives.

“I really did blunder and didn’t understand the trauma that my father lived through, and his father before him,” said Linda. “Now, I kind of get it.”

Louie King, a Chinese-Canadian veteran who did publicly voice his thoughts on those dark years, said this: “If future generations don’t understand the history and the significance of what we did, then they won’t be able to defend our rights in the future, if they are taken away again. It’s not a birthright, believe me. Somebody paid for it.”

As Clement and her team add to the Paper Trail, they hope more stories will emerge from storage and shoeboxes.

“Each is a powerful but fragile document,” she said. “You have the story of the person who owned it and their photograph. You have the story of the community and their experiences, and the suffering they went through. And in the same piece of paper, you have the story of Canada.”

For more information on the Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, visit here.

Before you click away, we have something to ask you….

Do you believe that Canada needs more independent journalism? And that quality journalism should be freely accessible to anyone regardless of their ability to pay? Yes? Well, we have something in common then.

The Tyee is a reader-funded publication, meaning that our whole publication is made possible by readers who choose to support our work with regular monthly contributions, even though we don’t have a paywall. This amazing group of 5,000+ people allow us to pay our writers fairly and focus on going deep on stories that truly matter to our readers.

Here is a short primer on the news industry in Canada: ownership of news organizations is extremely concentrated with just a few companies owning most of the newspapers. And over the last few decades, these owners have been shutting down local papers and laying off newsroom staff, leaving fewer reporters to do more each day. These papers rely on advertising for a large part of their budgets, but advertising clients have been moving to other platforms for quite awhile now.

We have chosen a different path — rather than try to chase advertising dollars, we invest in high-quality articles that add real value to the public conversation. We hope, therefore, that what we offer is valuable enough to readers that they’ll chip in a bit of money each month so that we can keep doing it. Whatever money we receive, we invest all of it into making more impactful journalism.

Our supporters are the only reason we can keep publishing in-depth original journalism every day, and they are also the only way we can grow and do more.

If you want to help The Tyee grow our independent newsroom and do even more impactful journalism, please join Tyee Builders today. You choose the amount you give, and you can cancel at any time.

Click here to join now.

Article From: thetyee.ca

Author: Christopher Cheung