Soon, those fully vaccinated against COVID will receive certification to travel, known as a “vaccine passport” — and most Canadians are in favour.

A survey conducted in May found that 67 per cent of the population supported vaccine passports for indoor events. Following the announcement made by the Canadian government on Aug. 11, universities, provinces such as Québec, hospitals and many other organizations have also said that they would be using vaccine passports to control access to indoor spaces.

But how will vaccine passports work?

As experts, we see it akin to smoking prohibition indoors. As Dr. Michael Warner says, roughly 18 per cent of Ontarians smoke, yet they are barred from doing it indoors. Roughly 18 per cent of Ontarians are unvaccinated, which eventually will prohibit them from certain public spaces. COVID, like second-hand smoke, is an airborne threat and individuals who are unvaccinated are at a significant risk of spreading the disease indoors — even more so now with the highly transmissible Delta variant.

While vaccine passports are an effective tool in boosting vaccine uptake and securing our indoor spaces, there is a possibility that if implemented inequitably, this mechanism further marginalizes the most vulnerable members of our society. “We must consider undocumented individuals, the unhoused. Like all policies we must mitigate undue harms to vulnerable communities,” Dr. Gaibrie Stephen shared in a tweet, and we agree: equitable implementation of vaccine passports is important because not all of us live with the same privileges.

For example, proof of OHIP coverage is not required at vaccination clinics. This makes sense, because the virus does not care about your eligibility for OHIP or your identity. But this has led to many individuals without an OHIP card being unsure as to whether they can receive the vaccine. In April 2021, many individuals without OHIP cards were told that they could not book online at city-run clinics in Toronto. Since then, we have seen many posters for vaccine clinics that state that one doesn’t need health insurance to get the vaccine.

However, these posters are commonly posted in English and on social media and not easily accessible to the most marginalized. Imagine living as an undocumented citizen, where you lack documentation to prove your residency. You don’t speak the language. You likely work in poorly ventilated — thus high risk — settings, yet you have limited work flexibility for you to take time off to access vaccines or vaccine information. You see signs containing illustrations of injections. But that sign also contains the words, “no” and “OHIP.” Would you come forward and ask if you can get the vaccine? Or will the simple measure of asking that question highlight that you are undocumented and — end up with you being deported?

Let us also not forget about those without homes. Wallet thefts are common in shelters and for those living on the street. Without a house to store critical documents, wallets are often used to store a person’s money, identification, health cards, and theoretically, their vaccine passports.

People experiencing homelessness are not necessarily anti-vaccine. When you are struggling to obtain food, clothes, safe shelter for the night, your first hot shower in weeks or months, waiting in line for a vaccine becomes a low priority. Raymond Macaraeg, a nurse practitioner working on a mobile vaccine bus in Toronto says that when the vaccine is brought to shelters and encampments, most of those who are present are often willing to take it; however, reaching the entirety of this transient population is a significant challenge for outreach workers.

Say you are an individual with a low income. You may be constantly working to make ends meet — and haven’t had the time or opportunity to get vaccinated, nor can you afford to take time off to rest to deal with possible temporary side effects. Because of the many barriers you face, you don’t have access to the vaccine — and thus, a vaccine passport. It’s a hot day and you are looking to grab a cheap drink and sit somewhere with air-conditioning during your break. Unfortunately, you can’t enter McDonald’s as they require a vaccine passport. Systemic barriers in access leading to the lack of one item has added yet another layer of inequity.

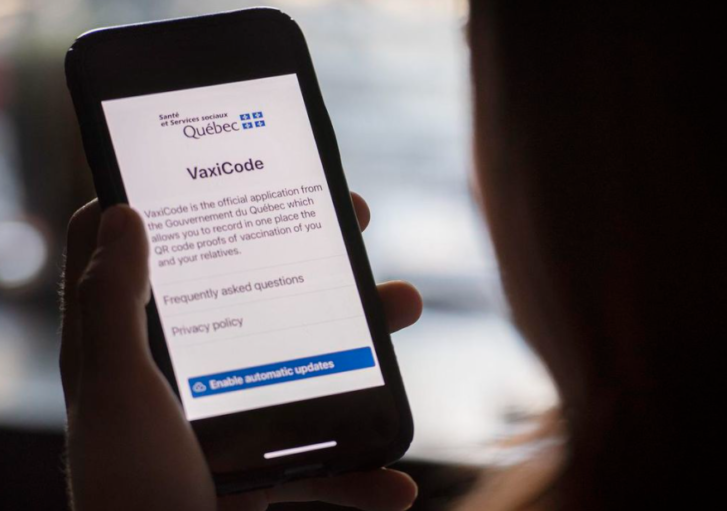

Despite all the posts of yellow vaccine cards on Ontarians’ social media accounts, implementing an inclusive COVID vaccine passport is not a trivial exercise. Unlike the paper documents showing our childhood vaccinations, used in schools, and occasionally when travelling internationally, this passport must be durable, hard to forge, portable, and easy to reobtain if lost. For those with English as a second language, low digital literacy, hesitant to share that they do not have OHIP or without a permanent home, it is yet another challenge on an already-difficult journey.

We need a vaccine passport solution that does not further marginalize the most vulnerable in society.

The authors are members of the Toronto Hub of the Global Shapers Community, a network of young people driving dialogue, action and change. Follow them @toglobalshapers.

Prativa Baral is a doctoral candidate at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Follow @tivabaral on Twitter.Dr Sonika Kainth Is a family physician working with marginalized communities. Follow @Sonika_K on Twitter. Puninda Thind is a sustainability professional and a climate justice organizer who is passionate about building resilient, sustainable and just communities. Follow @puninda on Twitter. Ben Wedge has is an MBA and engineer with seven years of experience in strategic consulting, passionate about creating a more sustainable world. Follow @benwedge on Twitter.

Article From: The Star

Author: Prativa Baral, Sonika Kainth, Puninda Thinda and Ben Wedge