Professor Cheryl Thompson talks Martin Luther King Jr. and community collectivism

The last two years have forced us to look at society’s deep contradictions and ask ourselves: what has really changed for equity-deserving communities? For Cheryl Thompson, professor in the School of Performance, the recent book bannings in the U.S. is an opportunity to look back through history to see how we’ve arrived here.

And for her, book banning represents a history of changing the window dressings instead of the rotting foundation. “Imagine if back in the ‘50s, instead of integrating the schools, they had integrated the school board?” she says.

Reflecting on the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., we talk about what lessons we can extract from his life, what happened to the civil rights movement after his assassination and how we’re at a similarly critical juncture.

Beyond the dream

Even as one of the leading civil rights figures of his day, King needed to confront his own approach to change in his lifetime. “There are certain people who believe in nonviolent activism, and that the way to progress is integration into the dominant culture,” says Thompson. “That was King’s belief.”

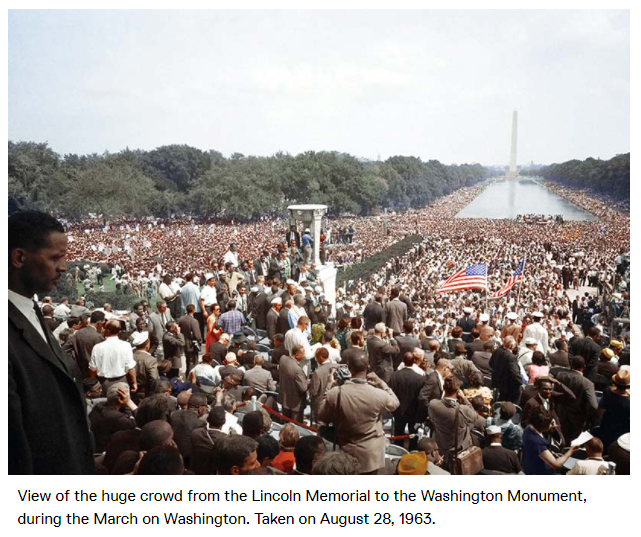

Thompson says King’s apex was really the period between the 1955 bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, external link, and the march on Washington on August 28, 1963, external link, where he delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech. “At that point, he was a hero,” says Thompson.

But by 1967, King was also talking about other issues circling the civil rights movement – labour, poverty, his anti-capitalist and anti-war stance – that would require major structural changes. This shifted him from national hero to persona non grata. “The dominant media culture was the cause of this shift, as reporting on King drastically changed between ‘67 up to his assassination in ‘68,” says Thompson.

“By ‘67, it was clear his original stance just wasn’t working,” says Thompson. “Yes there were some gains, obviously in 1965 the Civil Rights Act was passed. There’s the integration of major league sports, in Hollywood there’s Sidney Poitier and Cicely Tyson. This idea that diversity meant progress fed into the white liberal’s sense that things were getting better. But what they didn’t see was that the structures had stayed exactly the same. After 1963, a lot of people were being assassinated, like Medgar Evers and Malcolm X.”

Changing communities is the goal

“I think what’s happened really since the Martin Luther King era is that people started to realize that institutions don’t change unless communities change,” says Thompson. “Across the western world, anywhere where there have been liberation movements since the 1960s, people paid more attention to symbolic appointments than community uplift.”

We’re seeing echoes of this today, says Thompson. “When Biden says that we have to have a Black woman on the Supreme Court, I think, ‘okay, but do you care about Black women’s actual lives? Where are the policies that are helping Black women in their day-to-day?’ What you see in the intellectual, white middle-class liberal is this tendency to see appointments as progress. That’s why everyone thought Obama was going to change everything, because that was seemingly the highest appointment that you can get in America.”

To Thompson, we’ve been living in an illusion of progress, and the protests that occured after the murder of George Floyd in 2020 were a reaction to this. There’s now a shift toward collectivity that’s countering the idea that appointments mean equity.

Thompson urges us to see that change actually happens from the ground up. “Change happens when you can look around communities and you don’t see huge disparities – disparities in income or education.” If we care about individuals, we also have to care about the dialectical relationship between individuals, and we need to see that healthy communities are comprised of healthy individuals.

Unlocking history

“We focused so much on the African American fight for civil rights because it was recorded and documented in all the media coming from America. At the same time in the 1960s, there were movements across the Caribbean like in Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and Barbados, which all gained independence in the ‘60s as well as 17 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa,” says Thompson.

“These countries were looking to themselves and trying to undo histories of colonialism. And one of the reasons why Black movements have tended to be collective movements, is because there is that shared history of being colonized or having experienced imperialism. If you’re coming from that lineage, you’re always trying to find community.”

‘You are not an island’

After something so traumatic as a global pandemic or crisis, Thompson says we are entering the dangerous territory of turning inward and neglecting our larger communities. “There is this machinery that steps in to try to wipe our memories of this all. We consume more, go inward and become hyper individualistic.”

The urge to focus on yourself in a time of great uncertainty and trauma is understandable, says Thompson, but it’s important to train ourselves to know that we are not each an island. “You live in a world with other people that you have to know and understand. If we don’t attend to this, how can we grow as a society?” she says.

Step one can be books

Closing the gap between our experience and understanding others’ is how we form movements with momentum, says Thompson. “That’s why I bring it back to the banning of books. Reading books about other people’s experiences as a young person takes you outside yourself.”

Thompson remembers well when she first read The Diary of Anne Frank and the transformative effect it had on her life. “That was the first book that I’d read about a Jewish person. If I don’t read books about anyone other than myself, then I don’t know who they are. And I think that about white people who have never read a book written by a Black author, ‘how can you know me?’ And bringing it back to King, he was trying to close that knowledge gap.”

What critical race theory is trying to point to is the imbalance that we need to bring back in balance. “If you look at a reading list and every author on it is white, and 80 per cent male, maybe you want to look at that. It doesn’t mean that you’re taking anything away.”

What King’s legacy means today

Thompson points out that we are still having this conversation nearly 55 years after King’s death. “It takes a long time to shift a culture away from structures that have been at the root of the culture since its inception.”

But slowly, Thompson sees these shifts happening, and urges us all to continue to forge ahead for change as we emerge from lockdowns and look at the lingering inequities head on. “We’ve never lived in a moment where so many people are actually able to have conversations that are not rife with not knowing each other and looking at people of colour like an Other. Coming out of a major crisis, we really will have more in common than not. So we shouldn’t let that momentum fade.”

Small-scale engagements at your community level can change the lives of the people around you, says Thompson. “You don’t have to be Martin Luther King – when you scale it down to your local community, it becomes attainable.”

Thompson feels like there’s never been a time where average people have been more empowered as individuals, with access to social media to tell a story. Even coming out of the pandemic, we’re seeing substantial labour movements, external link gain momentum.

“I think the goal of this century is for everyone to become more empowered as a person. It’s a process. Understand that change is a process, that self knowledge is a process, but you have to be willing to undergo the process and not close the door because it gets uncomfortable. For me, I hope that people work through their own discomfort.”

Article From: Ryerson Today

Author: Michelle Grady