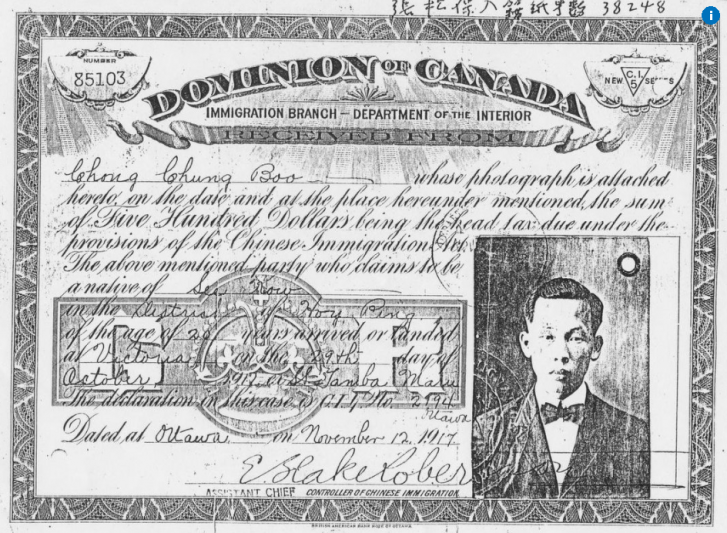

June 22nd Tuesday marks the 15th anniversary of the Parliamentary apology and redress for the racist Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act, thanks to decades of advocacy by the head tax payers, their families and supporters.

The 62 years of legislated racism ended in 1947, but it left permanent scars on the entire Chinese Canadian community and many generations of families burdened by financial hardship and family separation. Chinese men brought to Canada to build the Canadian Pacific Railway could not afford to bring their wives or children to Canada due to the $500 head tax.

Then in 1923, the Exclusion Act wiped out all hopes for family reunion. The Chinese Canadian communities were reduced to “bachelor societies” where the ratio of men to women was as high as 2,000 to 1. Racist laws denied Chinese Canadians and other Asian Canadians the right to vote until 1949.

The legacy of these racist laws is evident even today. Despite our long history in Canada, our community has not benefited from the depth of many generations of stable development here. We are still seen as perpetual foreigners and the “Yellow Peril.” These stereotypes have recently been weaponized during the pandemic and given rise to new heights of anti-Chinese hate.

While much of the spotlight has been on the incidents of anti-Asian racist attacks, much less attention has been drawn to the long lasting economic, political and social impacts of the systemic racism that is rooted in our nation’s historical injustices.

According to the 2016 census, the poverty rate for Chinese Canadians was 23.4 per cent, almost doubled that of the white population at 12.2 per cent, and comparable to that of Black Canadians at 23.9 per cent. These stark statistics confirm that the “model minority” myth of successful Chinese or Asian Canadians is exactly that — a myth. As with all communities, the Asian Canadian communities are not monolithic.

A recently released report, Colour-coded Retirement by Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, shows that Chinese seniors have the lowest average income ($28,200) and the highest poverty rate (25 per cent) among all racialized groups, including Indigenous seniors. Within the Chinese Canadian community, the only group of seniors that did well financially compared to others were those born in Canada. Yet, given the decades of exclusionary immigration laws and practices, this group of seniors represented only 3 per cent of the entire Chinese Canadian senior population.

Chinese Canadians, like other people of colour, are subject to pervasive racism that is structural and systemic in nature.

Two Canadian studies provide proof of anti-Asian racism in the labour market. A 2011 study supported by Metropolis B.C. found that applicants with a Caucasian name were 35 per cent more likely to be offered a job interview than someone with a Chinese or South Asian name, given an otherwise identical resumé.

In a similar study by University of Toronto and Ryerson University in 2017, applicants with Asian sounding names were 20 to 40 per cent less likely to be called for job interviews.

Meanwhile, our communities have yet to be reflected in the corridors of power. Whether it’s CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, the judiciary, or political office holders at all levels, Chinese Canadians remain woefully under-represented, and our voices effectively suppressed.

As we mark the symbolic importance of the historic Parliamentary apology in 2006 for the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act, we should acknowledge that much work still needs to be done before Chinese Canadians are fully accepted as equal citizens in a country we have helped to build.

We must face our long history of racism and white supremacy. What our communities need — and indeed what all racialized communities deserve — is for all of our governments and institutions to move beyond symbolic gestures and take concrete measures that would address the underlying social and economic racial inequities.

Let us define our society and our values by taking action against injustice. History has shown that we must demand accountability from those with power and influence, and insist that they lead with humanity and empathy.

Article From: The Star

Author: Avvy Go, Gary Yee.

Avvy Go is clinic director of the Chinese & Southeast Asian Legal Clinic.

Gary Yee is vice-president of the Chinese Canadian National Council for Social Justice, and he led the redress campaign in the late 1980s.