Seven-in-ten believe Canada’s health-care system is not well-prepared to handle a future pandemic

March 10, 2022 – Two years. Of illness and recovery. Of death and loss. Of scientific breakthroughs at breakneck speed. Of moments of unexpected kindness. Of anxiety and hope. Of solidarity and empathy, but lately, anger too.

How do Canadians sum up the more than 700 days since the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreaks worldwide a pandemic?

Data from a new comprehensive public opinion study – a joint project of the non-profit Angus Reid Institute and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation – reveals what people in this country have experienced during this unprecedented period, how they’re feeling now, and where they expect things to go in the months ahead.

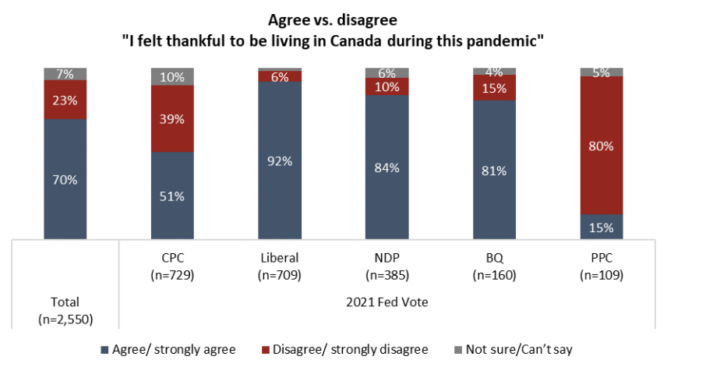

This first report in a series highlights the lived experience of Canadians over the last two years, and their perceptions of the ways the pandemic has changed our society. While a key sentiment underpinning the national attitude today is gratitude – indeed, 70 per cent say they are “thankful to be living in Canada” through this time – a darker mood prevails.

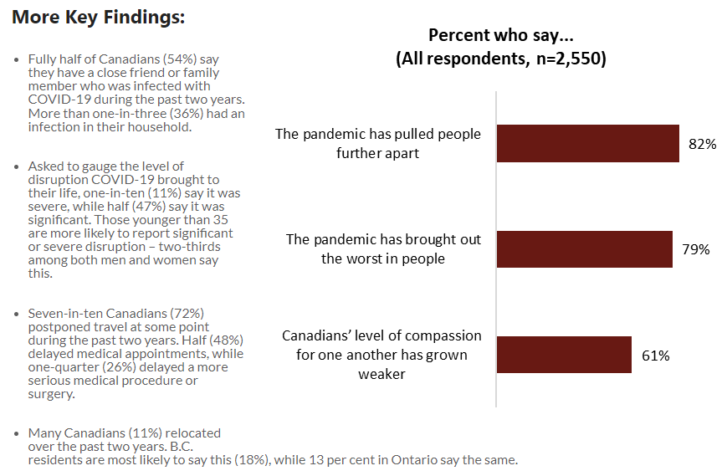

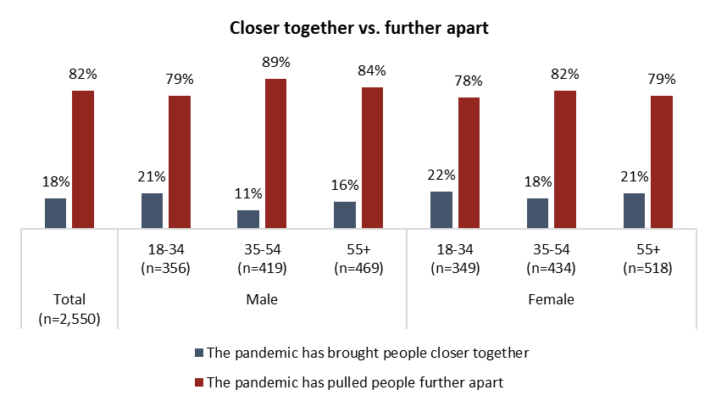

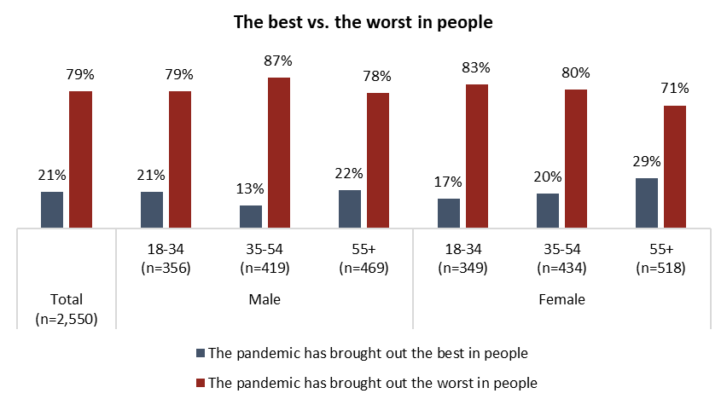

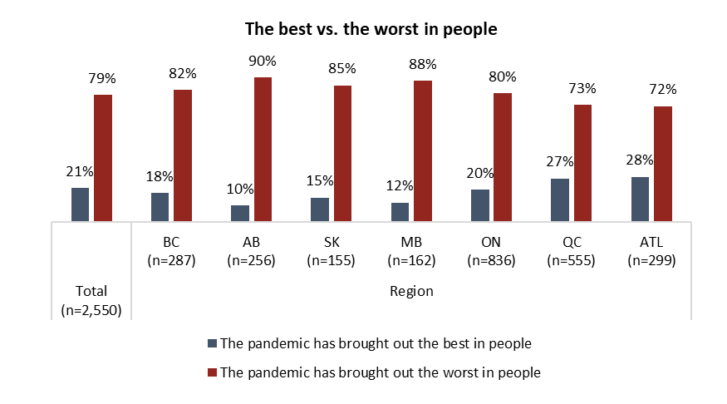

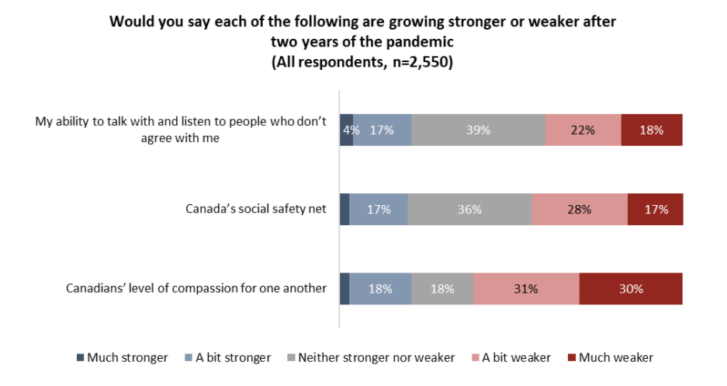

The findings are stark: an overwhelming majority (82%) believe the pandemic has pulled people apart as opposed to bringing them together (18%). About the same number (79%) say this period has brought out the worst, not the best (21%) in people. Nearly two-thirds (61%) say Canadians’ level of compassion for one another has weakened.

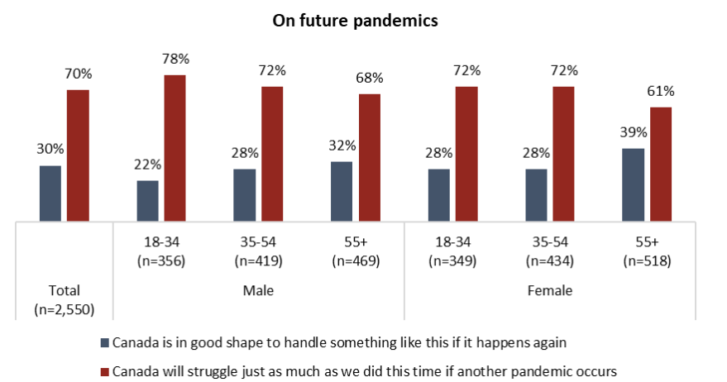

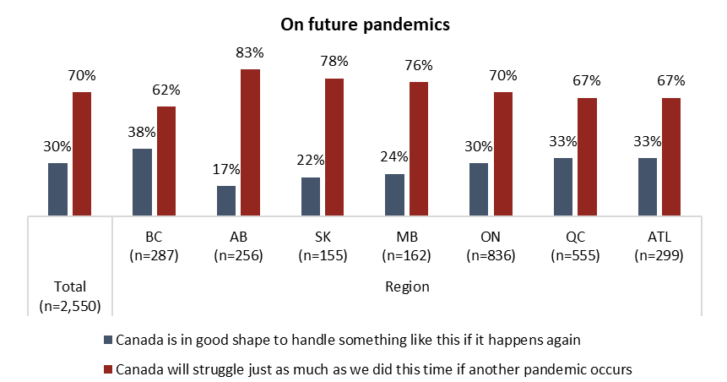

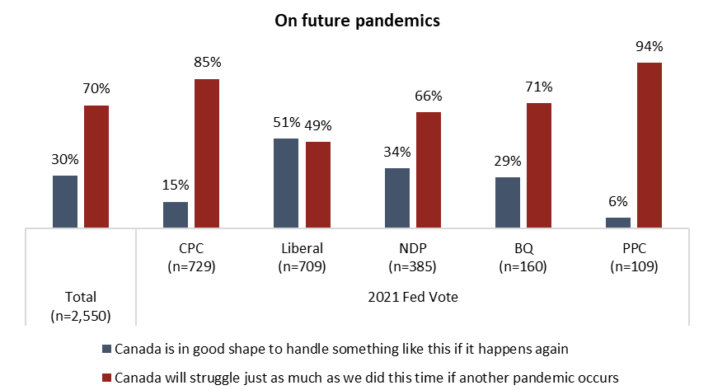

And despite the developments and lessons of the last 24 months, Canadians are jaded about how well this country is equipped to handle a future pandemic. Most (70%) believe Canada will “struggle just as much” in the next pandemic – while fewer than half that number (30%) say the nation is in “good shape” to handle something similar happening again.

About ARI

The Angus Reid Institute (ARI) was founded in October 2014 by pollster and sociologist, Dr. Angus Reid. ARI is a national, not-for-profit, non-partisan public opinion research foundation established to advance education by commissioning, conducting and disseminating to the public accessible and impartial statistical data, research and policy analysis on economics, political science, philanthropy, public administration, domestic and international affairs and other socio-economic issues of importance to Canada and its world.

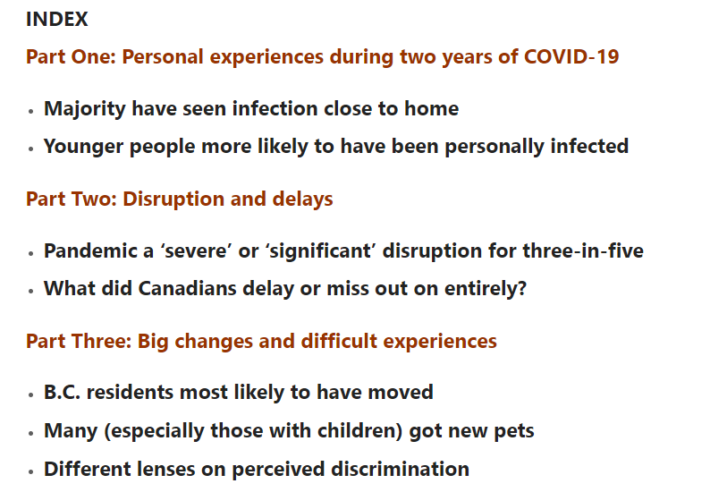

Part One: Personal experiences during two years of COVID-19

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 was a pandemic, the official beginning of viral spread at a speed and scale not seen since the 1918 Spanish flu. In the two years since that declaration, more than 37,000 Canadians have lost their lives and millions were infected with COVID-19. Over the half dozen waves since 2020, Canadians have experienced unprecedented economic and social disruptions as governments fought to contain the virus through restrictions on businesses, gathering and travel.

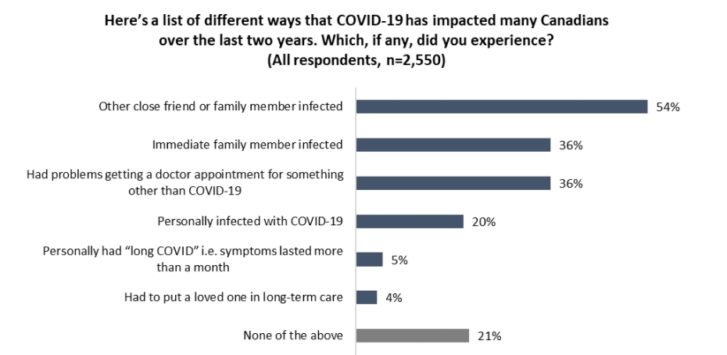

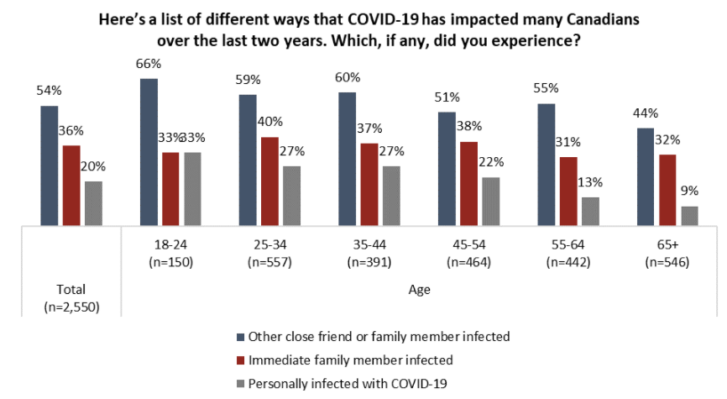

Majority have seen infection close to home

COVID-19 has entered the close circle of more than half of Canadians – 54 per cent say a close friend or family member has been infected with the virus since the beginning of the pandemic. One-third say an immediate family member caught COVID-19 and one-in-five were personally infected. Officially, Canada has had more than three million cases of the virus, but with official testing unavailable to many Canadians during the Omicron wave, the most infectious the virus has been, the true total of infections is likely much higher.

Of course, infection is not the only way Canadians’ lives have been impacted by the virus. One-third (36%) say they had problems getting an appointment with a doctor for something other than COVID-19 in the last two years.

Viral spread was not experienced evenly across the country. Alberta, Saskatchewan and Quebec have experienced the highest rates of cases per capita for provinces throughout the pandemic. In all three provinces, two-in-five (41%) say they know an immediate family member who was infected with COVID-19. The Atlantic provinces, on average, have been some of the most successful at limiting the spread. In that part of the country, one-in-ten say they were personally infected, the lowest of any region (see detailed tables).

Younger people more likely to have been personally infected

Throughout the pandemic, younger Canadians have been less likely to be concerned about personally contracting COVID-19. As well, they’ve been less likely to follow the recommended protocols. Though, notably, they were also much more likely to be working jobs which put them in a public facing position which made them more at risk to COVID-19 exposure.

Related: One-in-five Canadians making little to no effort to stop coronavirus spread

Given this, younger Canadians are much more likely to report a personal COVID-19 infection. One-third (33%) of 18- to 24-year-olds say they caught the virus, the most of any age group. As well, two-thirds (66%) in that age group report they knew close friends or non-immediate family members who were infected by COVID-19. This is reflected, as well, in Canada’s official case counts, which show higher rates of infection among younger Canadians.

Canadians of retirement age, who were consistently more personally concerned about catching the virus throughout the pandemic, and more likely to follow safety precautions, report low numbers of personal infection, as well as knowing fewer in their circle who contracted COVID-19:

Part Two: Disruption and delays

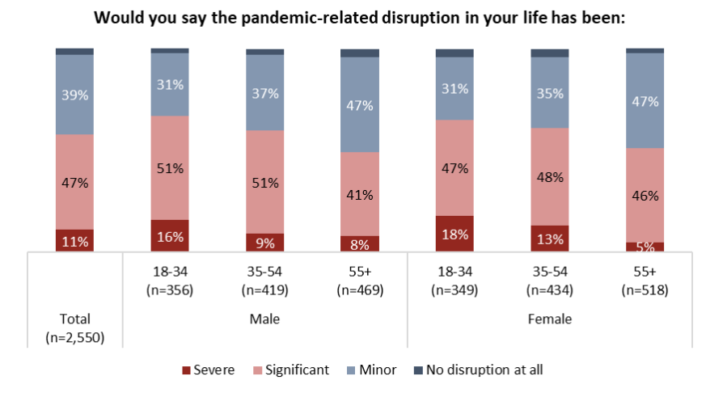

Pandemic a ‘severe’ or ‘significant’ disruption for three-in-five

The majority felt like their life was derailed by the pandemic. Approaching half (47%) describe the pandemic-related disruption they experienced in their life as ‘significant’, while a further one-in-ten (11%) would describe it as ‘severe’. For two-in-five (39%), the disruption was more minor and a handful (4%) felt like their life continued on its normal course.

The sentiment of disruption is not even across age groups. Two-thirds of men (66%) and women (64%) aged 18- to 34-years-old felt their life was interfered with significantly or severely by COVID-19. That proportion falls to half for men and women over the age of 54. Instead, half of men and women that age felt the pandemic altered their life in a minor way, the most of any demographic:

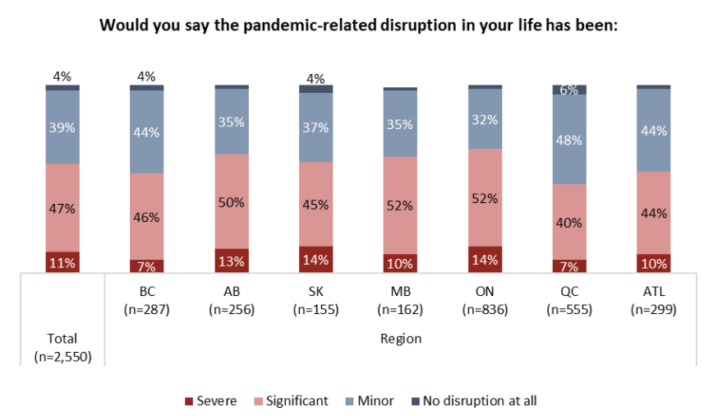

The disruption of COVID-19 was not felt equally across the country. Three-in-five in Alberta (62%), Manitoba (62%) and Saskatchewan (60%), and two-thirds (65%) in Ontario, felt the unplanned changes brought by the pandemic severely or significantly altered their life. The restrictions brought in to fight the spread of COVID-19 varied in those four provinces. For example, Ontario’s schools were closed for more weeks than any other Canadian jurisdiction. The Prairie provinces, meanwhile, were some of the first to open up last summer.

More than half (53%) in Quebec say the pandemic brought only minor disruptions, or none at all, to their lives. This despite their province instituting curfews twice to slow the spread of COVID-19.

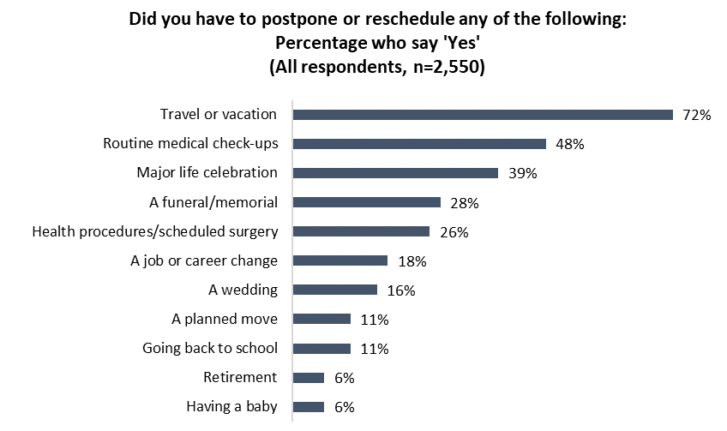

What did Canadians delay or miss out on entirely?

The most common item rescheduled was travel. Fully seven-in-ten Canadians (72%) say that they postponed a trip. This sacrifice likely added to the indignation Canadians felt when multiple politicians were revealed to have travelled over the winter holidays in late 2020 after asking their constituents not to. Health procedures such as routine checkups and surgeries were also postponed as resources went to serving COVID-19 patients.

Other major life celebrations, including birthdays, funerals, and weddings were delayed:

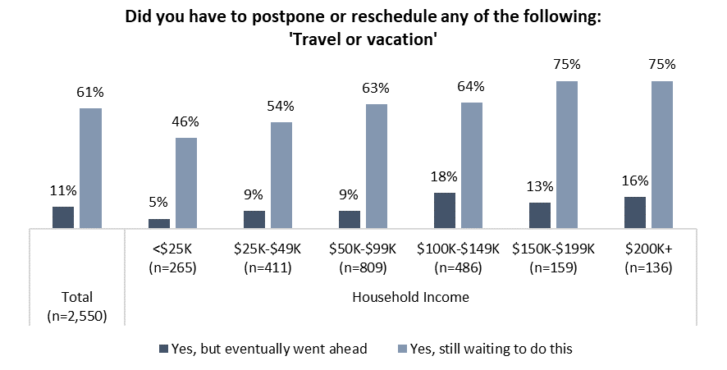

Half of Canadians across each income level say that they delayed their travel – or still are – though those with higher household incomes are more likely to say this:

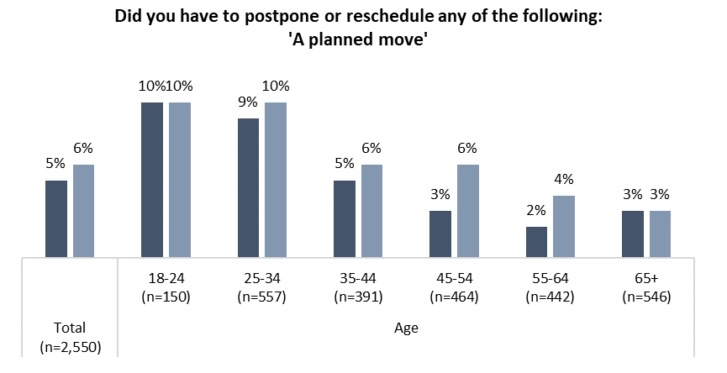

For many younger people, the pandemic has been an impediment to starting the next chapter of their lives. One-in-five 18-to-34-year-old’s say that they postponed or rescheduled a plan to move, with half of that group saying they are still waiting to do so:

Part Three: Big changes and difficult experiences

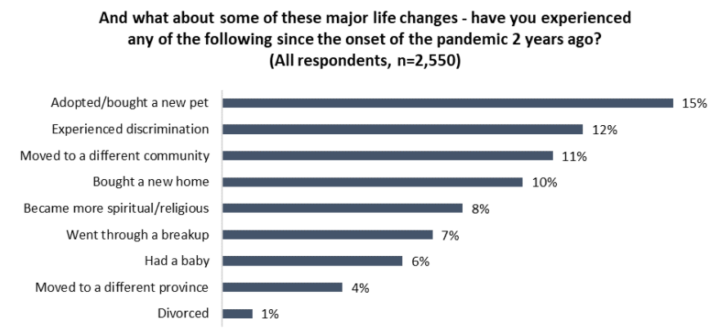

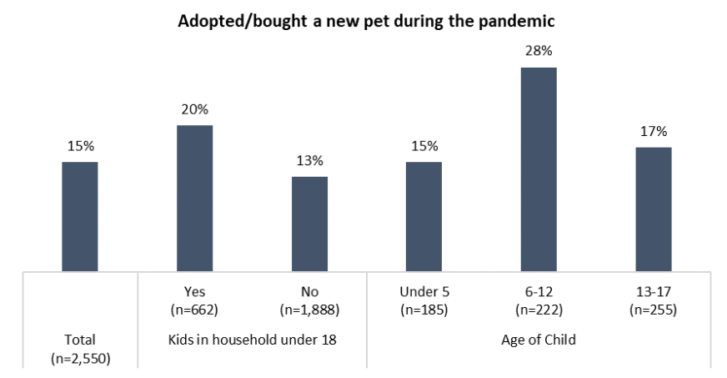

The upheaval of the pandemic didn’t only cause delays and disruptions, it also brought significant life changes and experiences to many Canadians. More than one-in-eight (15%) say they adopted or bought a new pet, one-in-ten (11%) moved to a different community and one-in-ten (10%) say they bought a new home. One-in-20 say they had a baby and eight per cent said they became more spiritual or religious during the course of the pandemic.

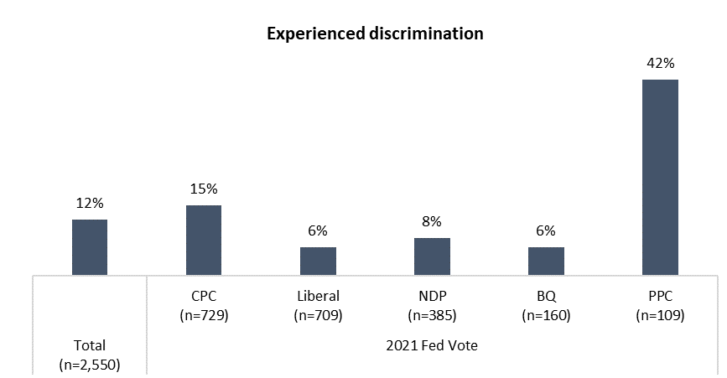

There were also more negative experiences. One-in-eight (12%) say they experienced some sort of discrimination and seven per cent went through a breakup.

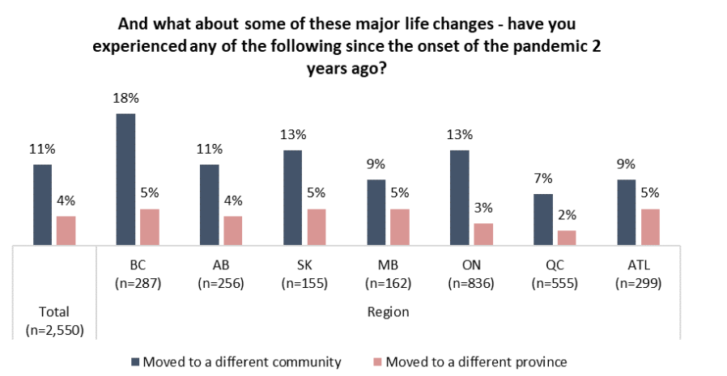

B.C. residents most likely to have moved

The shift from the work office to the home office was one of the more significant changes to the economy in the last two years. That, compounded with skyrocketing real estate prices in Canada’s biggest cities – especially Toronto and Vancouver – pushed many to cheaper locales. British Columbians are most likely to say they moved during the pandemic. Approaching one-in-five (18%) say the moved to a different community, the most of any province.

As well, three-in-ten (28%) of 18- to 24-year-olds say they packed up and changed communities in the last two years, the most of any age group (see detailed tables).

Many (especially those with children) got new pets

The surge in demand at animal shelters and rescue organizations across the country was another pandemic phenomenon. Canadians who were spending more time at home due to shuttered schools, offices, restaurants and gyms decided it was the perfect time to welcome a furry friend into their lives. Households with children are more likely to say they adopted or bought an animal companion during the pandemic, including three-in-ten (28%) of those with a six- to 12-year-old at home:

Different lenses on perceived discrimination

The pandemic brought with it a brighter spotlight on racism and discrimination. Past ARI studies revealed the extent to which Asian Canadians, and especially those of Chinese descent, experienced the ugliness of racism throughout the pandemic.

Related:

- Blame, bullying and disrespect: Chinese Canadians reveal their experiences with racism during COVID-19

- Anti-Asian Discrimination: Younger Canadians most likely to be hardest hit by experiences with racism, hate

One-in-eight (12%) of Canadians say they experienced some form of discrimination during the last two years. This experience was more common for respondents who identified as Indigenous or Asian.

Ethnicity is not the only lens through which Canadians perceive discrimination. Respondents from lower income households were slightly more likely to say this (see detailed tables). It was also demonstrated by the two-in-five (42%) of those who voted for the People’s Party of Canada last fall who claimed they too experienced prejudice. Notably, many who shunned inoculation – who also form a significant portion of the PPC’s base – felt they were discriminated against by vaccine mandates.

Part Four: Who’s better or worse off?

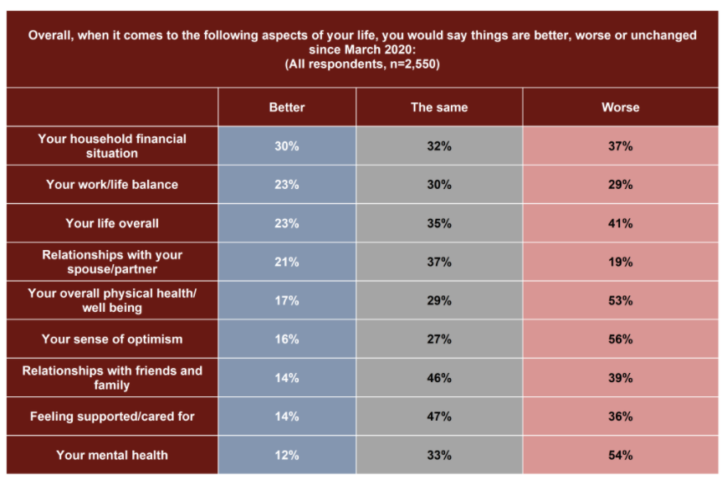

Respondents were asked to assess various aspects of their life after two years of COVID-19 and whether they were better, worse or the same. On the balance, Canadians’ assessment is more negative than positive.

Two-in-five say their life overall is worse than it was before the pandemic, more than the one-quarter who say their life is better. When it comes to their mental health, their sense of optimism, and their physical well being, Canadians are much more likely to say the pandemic did damage than improved those aspects:

The worst years of your life?

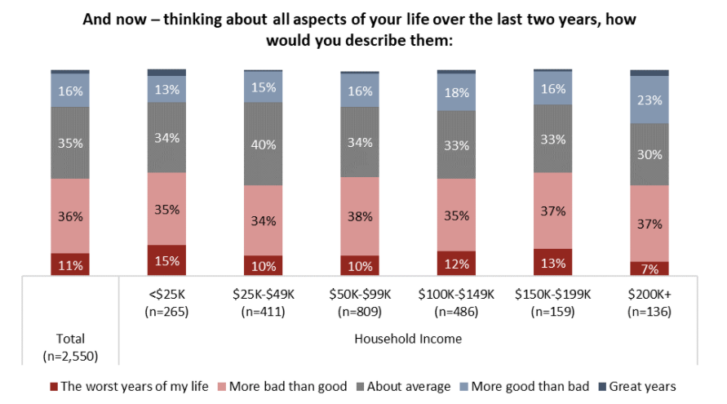

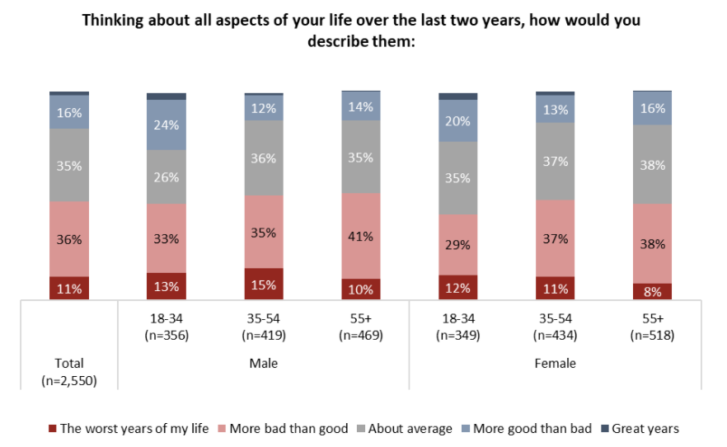

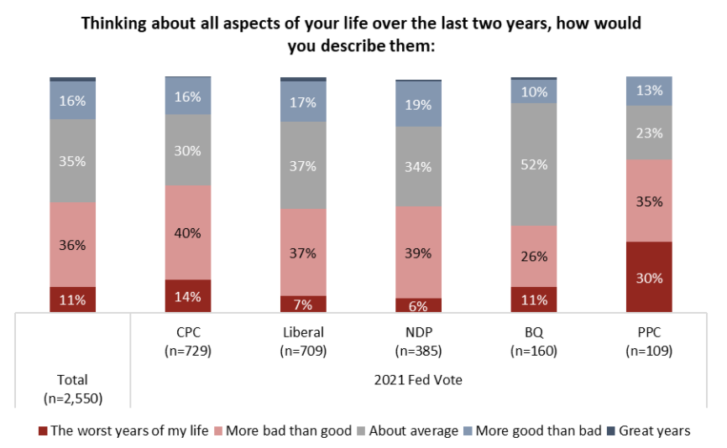

Given those appraisals, it’s perhaps little wonder that half (47%) of Canadians feel the last two years were by and large more bad than good, including one-in-ten (11%) who say they were the worst years of their life.

This sentiment was not consistent across income levels. Though at least 44 per cent in every income bracket say the last two years were challenging, a larger proportion – one-quarter – in the highest income households say there were more positives than negatives since the outbreak of the pandemic.

Conversely, 15 per cent of those in the lowest income bracket say this has been the worst period of their life. This is a proportion double the size of those in the highest income bracket:

Younger Canadians, too, found more positives than older ones from the last two years; one-quarter of men (27%) and women (24%) aged 18- to 34-years-old say either they were great years or there was more good than bad to them. Still, a plurality across all age groups felt there was more bad than good times since 2020:

Regionally, the assessment is varied as well, though at least two-in-five in every region in the country felt the last two years brought more negatives than positives. Western Canadians are more likely to find more fond memories of the last two years – one-in-five in B.C. (19%), Alberta (21%) and Saskatchewan (20%) say there was more good than bad about the last two years, the highest levels in the country (see detailed tables).

For People’s Party of Canada voters, who as noted above are more likely than other partisans to feel they were discriminated against over the last two years, three-in-ten describe the time since March 2020 as the worst years of their lives:

Two-in-five struggled to care for others

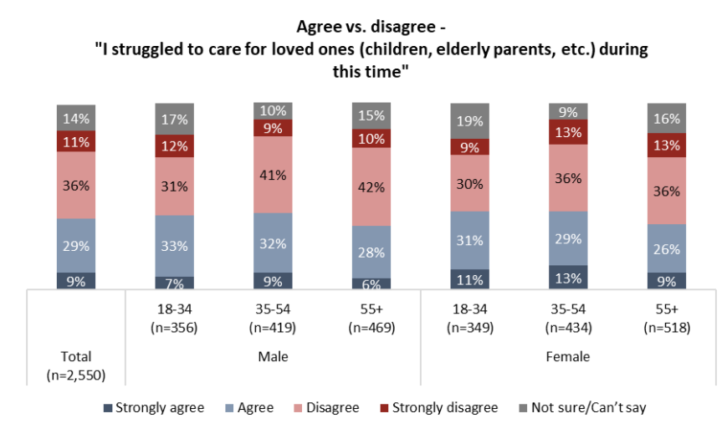

For many, these struggles are rooted in care for others. Two-in-five Canadians (38%) say that they had a difficult time caring for loved ones at some point over the past two years. This is an experience widely held; at least one-in-three across all age and gender groupings have had a challenge in caring for someone, though women under the age of 55 were more likely to say this:

Part Five: State of the nation after two years

Polarization in Canada on the issue of COVID-19 was not always a reality. In the early months of the pandemic Canadians were concerned about potentially making others sick and applauding of government leadership. Disagreement over restrictions and dissatisfaction with leaders in many parts of the country led to increasing angst in Canada, most prominently on display in recent ‘Freedom Convoy’ protests.

Related: Canadian views of Ottawa protests

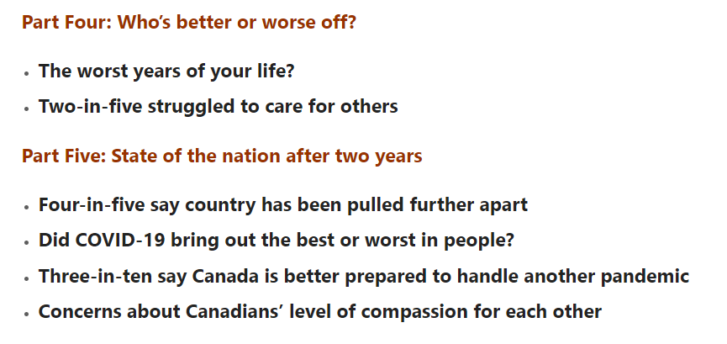

Four-in-five say country has been pulled further apart

Asked how they would describe the change they have seen in the country over the past two years, Canadians are much more likely to see the country as further apart rather than closer together. These opinions are remarkably consistent across age and gender, as well as region by region (see detailed tables):

Did COVID-19 bring out the best or worst in people?

Canadians sacrificed greatly over the past two years. Nine-in-ten of those five years of age and over have had at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and millions stayed home, wore masks, and respected the wishes of their compatriots who were concerned about illness. Despite this, Canadians on the whole are more likely to say that the pandemic brought out the worst in people.

Those in the prairies are most likely to say that the pandemic has had a negative effect on people in the country, led by Alberta, where nine-in-ten (90%) say this:

Three-in-ten say Canada is better prepared to handle another pandemic

As daily positive cases diminish and provinces remove health restrictions, most are casting a skeptical eye toward future pandemic threats. In the event that Canada did face another health crisis like this, Canadians are not certain that the health-care system is in a better place to handle it. Seven-in-ten (70%) say that the country would struggle just as much next time. Canadians over the age or 54 are most optimistic about preparedness, but still say this at minority levels:

Two-in-five B.C. residents (38%) and one-in-three of those living in Quebec (33%) and Atlantic Canada (33%) say Canada is in good shape to handle something like this if it happens again. Majorities in every region say the opposite:

One group of Canadians stand out amongst the others as most optimistic that the country has made strides in pandemic preparedness – past Liberal voters. This group is divided evenly on each side of the faceoff:

It is worth noting that though their mood is notably sour at the moment, the vast majority of Canadians say they are thankful that they were in Canada over these past two years and not elsewhere. This suggests some level of appreciation for the health-care system and workers in the country. Past Conservative and People’s Party voters are notable for their disagreement on this question:

Concerns about Canadians’ level of compassion for each other

The pandemic brought many challenges to Canadian society, as well as perhaps exposing fissures that were already there. After a trying two years, Canadians are more likely to feel the threads of communication, compassion and the country’s social safety net have frayed than thickened.

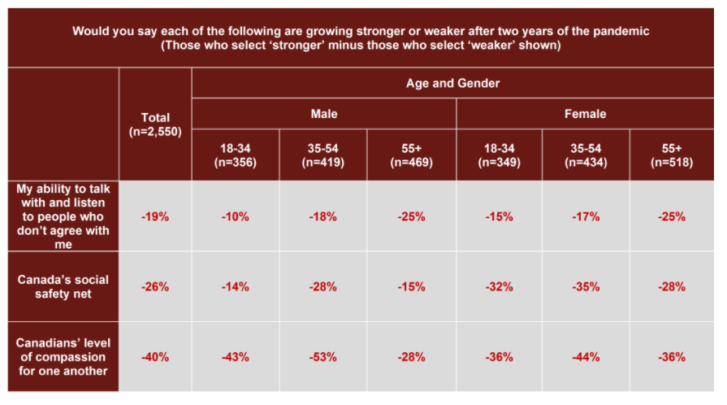

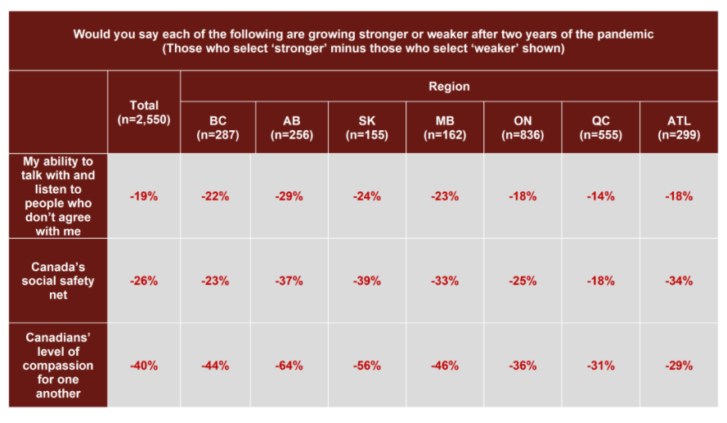

Three-in-five (61%) say Canadians’ level of compassion for one another has declined, three times the number who say it’s as strong as it ever was (18%) or has grown stronger (21%). A plurality (45%) believe Canada’s social safety net has weakened. And as many people who believe they’ve lost some of their ability to talk with and listen to people who don’t agree with them (40%) say that’s remained consistent (39%) despite the last two years:

Across age and gender lines, those who believe each of those elements of society are growing weaker outnumber those who believe the opposite. However, women are much more likely to say the social safety net is fading than men. For 35- to 54-year-olds, they are more likely to feel Canadians have lost some compassion for one another than younger and older Canadians of the same gender:

The balance of perceptions about Canada’s social safety net is also tilted more negative in Atlantic Canada and the Prairies. Meanwhile, Albertans and Saskatchewanians are more likely to feel compassion among Canadians has weakened than residents of other provinces:

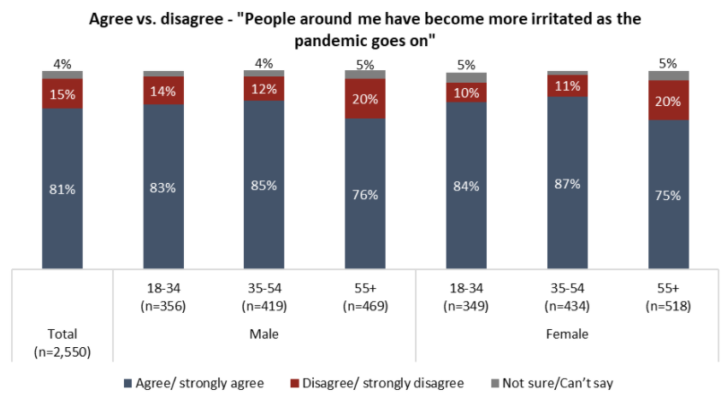

As the pandemic has worn on, perhaps compassion has been replaced by irritation. Four-in-five (81%) see frustration rising since March 2020. The overwhelming majority across all age groups say this, but men and women older than 54-years-old are more likely to disagree:

Up Next: The second report in this ARI-CBC series will focus on Canadians and their mental health at the two-year mark of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Survey Methodology:

The Angus Reid Institute conducted an online survey from March 1 – 4, 2022 among a representative randomized sample of 2,550 Canadian adults who are members of Angus Reid Forum. For comparison purposes only, a probability sample of this size would carry a margin of error of +/- 2. percentage points, 19 times out of 20. Discrepancies in or between totals are due to rounding.

The survey was conducted in partnership with CBC and paid for jointly by ARI and CBC.

For detailed results by age, gender, region, education, and other demographics, click here.

For detailed results by ethnicity and whether or not respondents have children under 18 in their household, click here.

To read the full report, including detailed tables and methodology, click here.

To read the questionnaire in English and French, click here.

Image – Fusion Medical Animation / Unsplash

MEDIA CONTACT:

Shachi Kurl, President: 604.908.1693 shachi.kurl@angusreid.org @shachikurl

Dave Korzinski, Research Director: 250.899.0821 dave.korzinski@angusreid.org