Since November, Canadian children aged 5 to 11 have been eligible for their shots, but on average, just more than half have received them. Regional breakdowns tell a more complex story of income, race and other inequities

Since the approval of the first COVID-19 vaccine for kids 5 to 11 last November, Frederic Buyana has gotten into the habit of heading to the neighbourhood bus stop to chat with parents waiting to pick up their kids after school. The topic of conversation? The importance of getting children vaccinated against COVID-19.

And because Mr. Buyana was also once a newcomer to Canada, he’s been able to use his own experience to connect with and help others. Many parents are happy to listen, whether it’s at the bus stop, the food bank or knocking on doors in the neighbourhood. Mr. Buyana, who has degrees in psychology and social work, has spent the past year focused primarily on providing COVID-19 outreach and support as part of his job with the Somerset West Community Health Centre.

The work he’s doing is part of a broader strategy at some local community health centres in the Ottawa area to take a targeted approach to vaccine support. He answers questions and provides accurate information to individuals who are often juggling many more urgent daily needs, such as providing food for their kids. Some of them may also struggle with English or French, have a long-standing mistrust of government or have been influenced by false information they read online.

“I tell them … I’ve been vaccinated, my kids have been vaccinated,” said Mr. Buyana, an African, Caribbean and Black mental-health navigator with the Ottawa Newcomer Health Centre, part of the Somerset West CHC. “Don’t trust that misinformation you are getting.”

Last November, Mr. Buyana started working with a mother of three who needed help with legal and financial matters. As he got to know her, he used the opportunity to open up the conversation about vaccination and alleviate some of her fears about the safety of the shot. Thanks to his help, the woman decided to get herself and her three children vaccinated and now advocates for others in the community to get theirs.

“When we build that trust with them, we can discuss vaccination,” said Mr. Buyana, who uses his French and Swahili language skills to make it easier to connect with community members in their first language.

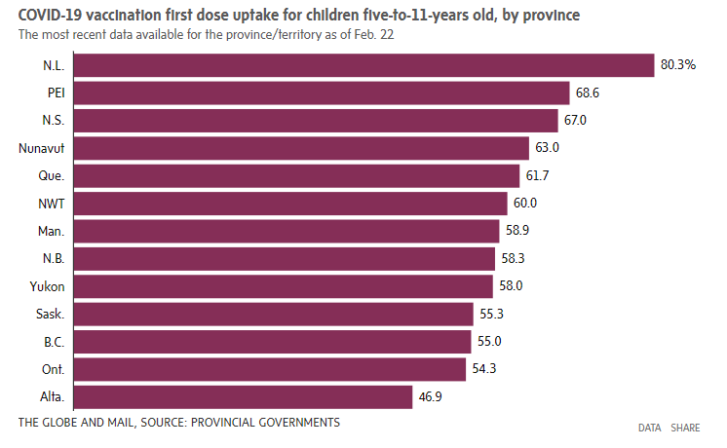

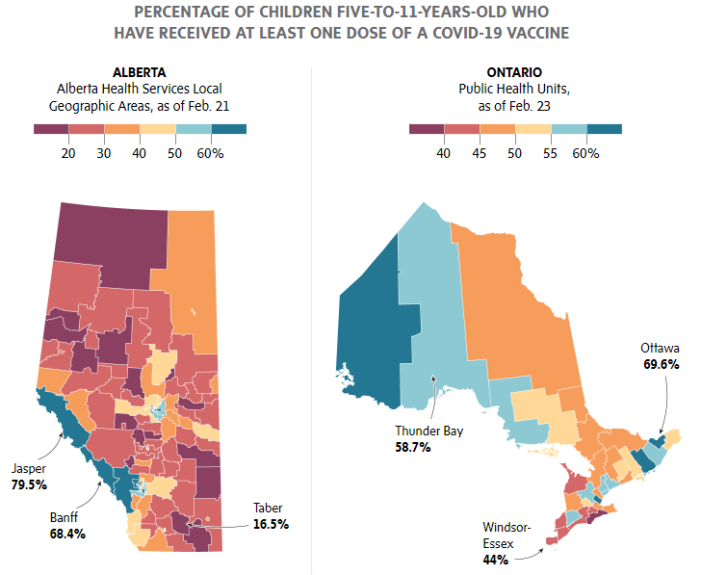

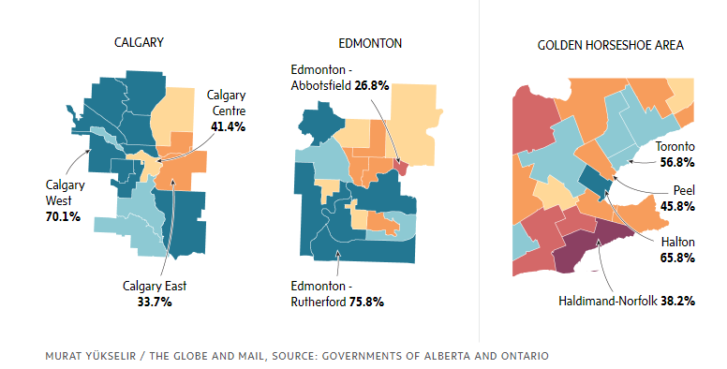

It’s one success story that could serve as a road map for many other communities grappling with low uptake of COVID-19 vaccines for kids 5 to 11. Across the country, 92 per cent of people 18 and older have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, but for kids 5 to 11 the average is only 61 per cent, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. That average only tells part of the story, as some high-income areas in Canada are reporting upward of 90 per cent of kids 5 to 11 being vaccinated, while other areas – notably lower-income, racialized communities, as well as remote and rural ones – have rates well below 50 per cent, with some dipping as low as the teens or even single digits. The move by many provinces in recent weeks to relax public-health restrictions, including an end to school mask mandates in some provinces, could also complicate work to improve childhood vaccination rates.

In Mr. Buyana’s Somerset West neighbourhood, which has a significant number of racialized individuals, as well as many low-income households and a growing population of homeless people, the vaccination rate of kids 5 to 11 is 61 per cent, above the Ontario average of 54 per cent. But in Rockcliffe Park, one of the most affluent areas in the city, the vaccination rate in that age group is 84 per cent.

In Toronto’s high-income Lawrence Park South neighbourhood, 84 per cent of kids had received at least one COVID-19 dose as of mid-January, compared with 33 per cent in the Black Creek area, a lower-income, highly racialized area.

In Alberta, the childhood vaccination rate in the Calgary West neighbourhood is 70 per cent, compared with 16.5 per cent in Taber, a southern community with a significant Mennonite population. While the Mennonite church officially endorses COVID-19 vaccination, many church members are hesitant or opposed to vaccines.

The reasons for low vaccine uptake among the 5 to 11 cohort are complex and vary by demographics and geography, with lower-income and racialized individuals often facing more barriers to vaccine access.

Health experts across the country say many parents are hesitating to get their kids vaccinated because of concerns over safety, particularly as the Pfizer-BioNTech shot, the only one authorized for children 5 to 11, has been linked to rare cases of heart inflammation (cases are generally mild and do not require hospitalization). Others question why children need to be vaccinated at all, as the majority of them experience mild infections.

So far, no province or territory has indicated it will mandate vaccines for school attendance, although some medical experts feel such measures may eventually be brought in to control outbreaks and keep schools open. In some parts of the country, municipalities and schools have required those 12 to 17 to be vaccinated to participate in some recreational sports or other activities, but few have extended such requirements to children 5 to 11. Some areas have lifted those mandates or say they will in the near future.

Alberta has the lowest vaccination rate of kids 5 to 11 in Canada, with only 47 per cent having received at least one dose. The urban centres of Calgary and Edmonton have higher rates than almost anywhere else in the province.

Some regions have a long-standing history of vaccine hesitancy and those issues are playing into low coverage rates, said Kristin Klein, lead medical officer of health for communicable diseases at Alberta Health Services. “We do have some communities that are more vaccine hesitant than others. We see that in our routine childhood [immunization] programs as well,” Dr. Klein said. “Every community has its own identity and some of that is concerns about vaccines and vaccine safety and hesitancy.”

Only 27 per cent of children 5 to 11 have received a first dose in Red Deer County, compared with 67.5 per cent in Edmonton’s Sherwood Park. Elsewhere in Alberta, the rates are even lower. In High Level, an area in the northwestern part of the province, only 12.5 per cent of five- to 11-year-olds have received at least one dose. In Two Hills County in northeastern Alberta, the rate is 7.5 per cent.

Lisa Jane de Gara, who has worked on vaccine uptake in the province throughout much of the pandemic, said for some Albertans, such as those in rural or agricultural communities outside of the big cities, resistance to vaccines is linked to more extreme political views opposing perceived government overreach or any threats to personal freedom.

Ms. de Gara said she was working at a vaccine clinic in a parking lot last year, before a vaccine for five- to 11-year-olds was even approved, and a protester disrupted the event, falsely convinced organizers were going to vaccinate children against their parents’ wishes.

The problem is significant enough that some officials and organizations in Alberta are reluctant to be seen as a cheerleader for COVID-19 vaccines because of concerns they could be targeted by anti-vaccine groups, Ms. de Gara said. For instance, some community groups have declined to post information about COVID-19 vaccines in their windows because they don’t want to attract the ire of anti-vaccine protesters, she said. Other community groups opted not to hold vaccine information sessions for the same reason, she said.

“Many public entities are frightened of drawing that public attention, either in person or online,” Ms. de Gara said.

Dr. Klein said the province will continue to offer pediatric vaccines in a variety of places and ensure people have convenient access to vaccination, regardless of where they live. She said the province has been working with community leaders and other trusted figures who can spread factual information about the importance of vaccination. But at the end of the day, it’s up to parents to make those decisions when they are comfortable and ready, she said.

“We can’t just increase rates by knocking on everyone’s door,” Dr. Klein said.

Some experts say messaging about the importance of children being vaccinated has been muddled since the vaccine was first approved, which is likely contributing to the slow uptake.

When the vaccine was approved last November, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), an expert panel that guides health officials on how to implement new vaccines, said provinces “may” offer the vaccine to children.

While many parents may not monitor NACI’s guidance, health officials and medical professionals follow their statements closely. Across the country, vaccination rollout plans and recommendations to patients are typically based on what NACI says.

“[NACI recommendations] filter through in terms of how much the provincial and territorial health bodies are able to push vaccination, or encourage vaccination,” said Manish Sadarangani, director of the BC Children’s Hospital Vaccine Evaluation Center. “That was not the strongest possible recommendation,” he added.

Dr. Sadarangani said given the concerns over the rare risk of heart inflammation in kids after vaccination, it’s understandable NACI took a cautious approach at first.

But some experts feel the initially lukewarm language sent the wrong message about the importance of kids getting vaccinated.

NACI strengthened its recommendation last month to say kids 5 to 11 “should be offered” the vaccine in light of mounting safety evidence and research showing vaccinated children are less likely to suffer from multisystem inflammatory syndrome, a rare but serious complication that can occur after a COVID-19 infection.

Matt Strauss, acting medical officer of health in Haldimand-Norfolk, a predominantly rural part of Southwestern Ontario that has the province’s lowest average vaccine uptake among kids 5 to 11, said NACI’s initial guidance meant he wasn’t encouraging widespread vaccination of kids under 12.

Now that it’s been updated, he said, “We can be more enthusiastic about recommending that it be offered,” but that families should make their own decisions.

Some say it took too long for NACI to strengthen the recommendation. Bonnie Henry, British Columbia’s Provincial Health Officer, told reporters last month she was “disappointed” NACI didn’t give a stronger endorsement to the vaccine for five- to 11-year-olds up until now.

Andrew Boozary, executive director of social medicine at the University Health Network in Toronto, said any variation in messaging from health leaders about the safety and importance of vaccination can erode trust.

“It has ripple effects across the country,” Dr. Boozary said. “It has real implications for what we’re going to see with respect for uptake.”

In addition to inconsistent messaging, many health experts say the prolonged closing of schools over the holiday break led to a slower rollout because some provinces weren’t able to offer in-school vaccine clinics, meaning parents had to seek out appointments on their own time. Ève Dubé, a medical anthropologist at Quebec’s National Institute of Public Health, said this is especially true for parents who have to work, who don’t have access to transportation to a clinic or who face other barriers.

Making vaccine clinics accessible – with numerous locations and flexible hours – as well as providing no-appointment-needed walk-in options, are known ways to increase uptake, she said.

Despite the sluggish rates, many experts remain optimistic that targeted campaigns could still help. In Manitoba, many First Nations communities, which have a history of vaccine hesitancy, have high rates of COVID-19 vaccine coverage, owing in large part to locally driven campaigns, said Joss Reimer, medical lead for the province’s vaccine implementation task force.

“That’s really thanks to the First Nations leadership that have taken over the rollout in those communities,” Dr. Reimer said, adding that hearing information about vaccines from trusted community sources has made a big impact.

But Manitoba is also facing challenges in many of its southern communities, Dr. Reimer said. While there is a history of vaccine hesitancy in those areas, many individuals in those communities have also been targeted on social media by anti-vaccination groups promoting false information, Dr. Reimer said. “It’s been a well co-ordinated approach on those communities that already had some hesitancy and concern about government in general, vaccines in general,” she said. “They’ve been able to leverage that and make it bigger.”

She tries to remind parents that while most children have mild COVID-19 infections, some experience serious illnesses that require hospitalization, and it’s not always easy to predict who is at risk. “We are seeing children end up in the hospital. We are seeing children end up in the ICU,” Dr. Reimer said. “And we’re not seeing them in the hospital or the ICU because of the vaccine.”

With a report from Andrea Woo

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: CARLY WEEKS