If Afrigen Biologics succeeds it would be a huge health win for a part of the world that doesn’t yet produce very many vaccines.

You are reading part 2 of Fighting for a Shot.

CAPE TOWN, South Africa—Petro Terblanche has just settled into a chair in her office with a cappuccino when the insectlike whine starts up from the other side of the wall.

Again.

For months, the constant clamour of drills, hammers and saws has been the soundtrack to meetings, lunch breaks and media interviews in this lab of shiny walls and gleaming equipment, the footprint of which has continued a slow outward creep inside an unremarkable row of brick warehouses in Cape Town.

The youthful staff wandering the bright white hallways — past the popcorn machine in the foyer that anchors the start-up vibe — seem not to notice the commotion, accepting it as part of the bargain of being a part of something totally new.

Still, as the drilling begins anew, Terblanche, their leader, a gregarious scientist-turned-business person, shoots a glance over the top of her stylish reading glasses and sighs, suggesting the briefest of brief flickers of annoyance. “We all have our moments.”

Terblanche and her colleagues are very much having a moment. If all goes to plan — though mind, it’s an ambitious plan — their facility at Afrigen Biologics, in a quiet neighbourhood a stone’s throw from what is almost the southern tip of Africa, could upend global vaccine production.

As COVID-19 vaccines have flowed around the globe, the majority have been snapped up by wealthy countries, leaving billions unprotected. The fact that Africa struggled to get a consistent vaccine supply was, sadly, not surprising, Terblanche says.

“But we didn’t expect the lag time. For the first vaccine to fly to Africa was just so long after the rest of the world.”

Backed by the World Health Organization and increasingly watched by governments around the world, Terblanche and her team have made an early prototype of Africa’s first mRNA vaccine, using the same technology pioneered by Moderna and BioNTech.

Fully developing that prototype would be a huge health win for a part of the world that doesn’t yet produce very many vaccines.

But, more to the point, the next time a global pandemic requires a life-saving vaccine, the capacity that’s being created would mean Africa isn’t stuck waiting for the Global North to donate extra doses after its own populations are done with them.

The hurdles are significant. Two years after the first mRNA dose went into a volunteer’s arm, Afrigen faced the prospect of having to crack the COVID vaccine code all over again.

When a new type of coronavirus began to spread around the globe, Canadian health officials became fond of a particular phrase used at press briefings from coast to beleaguered coast: “We’re all in this together.”

More than two years later, that feels less like reassurance and more like a threat.

A pandemic is a case when the fates of the rich and poor are linked. As Canada raced to protect its own population by securing vaccine doses in 2020, there was little acknowledgment of the risk a new variant would be brewing among the billions of unvaccinated worldwide — a reality brought home by the Omicron wave. Canada bought up enough to double vaccinate its own population almost six times over.

Of course, it’s hard to argue with a country that protects its own citizens first. As flight attendants are fond of saying, you have to put on your own oxygen mask before you help the person next to you. But global health advocates argue that wealthy countries such as Canada took it a step further, giving their own peoples a plane’s worth of oxygen masks, flotation devices and the contents of the beverage cart, to boot.

Never mind that if the plane crashes — if the global pandemic isn’t brought to heel everywhere — we’re all going down.

Even countries with the money to buy vaccines have been unable to make deals or have seen deliveries arrive months late, while poorer countries that were promised donated doses have seen deadline after deadline pass them by.

While 85 per cent of Canadians are now vaccinated, roughly 10 per cent of Africa has the same protection.

In South Africa, the country that fought for free HIV drugs for all — which has equality built into its post-apartheid DNA — there is a palpable sense of anger.

There’s a suspicion that they were blamed for the latest COVID variant even as the new variant shone a big, blinking spotlight on the need to vaccinate the world.

“This goes to two centuries of history of our world,” says Terblanche. “There’s so many factors here, but what is true and real is as long as Africa provides supplies of essential medicines through humanitarian processes which do not make provision for local manufacturing, we will we will never be resource efficient or sustainable,” she says.

“We’re looking for a model of what the rest of the world has.”

For a growing number of people in Africa, it’s not just that donations are taking too long to arrive, it’s that they have to ask for them at all.

Instead, they’re wondering — why couldn’t we make our own?

“OK, the back door has to bang shut,” Caryn Fenner instructs, and the handful of visitors obediently shuffle forward to allow it to close.

To enter the rat warren of rooms inside the Cape Town warehouse where Afrigen hopes to eventually make its first mRNA vaccines, all visitors cram into a chamber the size of a bathroom — the space where scientists will one day switch from street clothes into scrubs, not so much for their own protection, but to avoid contaminating the precious liquid brewing inside. To avoid even air particles ending up where they shouldn’t, you can’t open the door into the facility until the chamber’s back door is closed.

When the front door finally swings open, it’s like being spit out onto the empty set for a TV show — one that’s set on a space ship. The walls are white and shiny. The rooms are mostly empty so far, allowing any voice that breaks the silence to ricochet freely. There’s a map posted outside to try to orient visitors, but as rooms give way to other rooms that give way to other rooms that all look the same, a tour guide is required, if not a trail of bread crumbs.

One of the riskiest things you can bring into a vaccine facility is sweating, breathing, skin-shedding humans, explains Fenner, Afrigen’s technical director. Many vaccine facilities automate as many processes as possible to reduce the number of people required inside, but as this will be a training hub for scientists from low-income countries, every effort is being made to minimize risk.

Needless to say, tours of vaccine facilities are rare.

But the process of construction has opened a rare window of accessibility for media to poke around here in Cape Town.

In the coming weeks, the facility’s HVAC system will be officially turned on, sealing off the facility to outsiders and activating a pressurized air system that makes sure the environment is contained, down to the tiniest particle.

Fenner estimates that a facility like this will cost about 10 times less than it would in Europe or the U.S., because everything from supplies to labour costs less. Of course, they’re often left waiting months to get supplies.

Afrigen moved into this space, chosen for its location in a light industrial area with good access to the airport, in the summer of 2020 — the previous tenant was using it for storage — and got to work. At maximum capacity, the “pilot scale” facility would be able to make 10 million vials, meaning 50 million doses, every year. For the first five years, most of what it produces would be used in clinical trials to make sure the vaccine is working.

The first piece of equipment to be installed — a silver cylinder that sprouts tubes like tentacles, that’s used to make big batches of DNA — is looking a little lonely, sitting by itself while other equipment languishes on backorder. It’s what’s called a demonstration model. Basically, the provider is letting Afrigen use it to see if the machine works for its purposes, and then, at a certain point, there’s an option to buy it at a reduced cost.

A lot of their suppliers have been generous with supplies or expertise in terms of helping Afrigen get underway, Fenner says.

Of course, the biggest thing they’re missing isn’t equipment, but technology.

While it’s true that scientists have been working with mRNA for years, so far, only two groups have been able to get their vaccines across the finish line and authorized, and they’re now household names as a result — Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech.

And they’re not sharing their secrets.

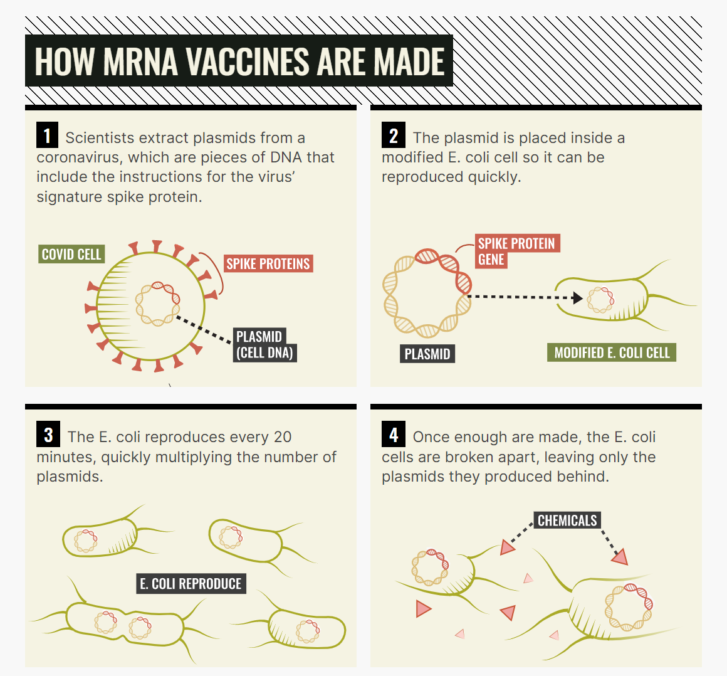

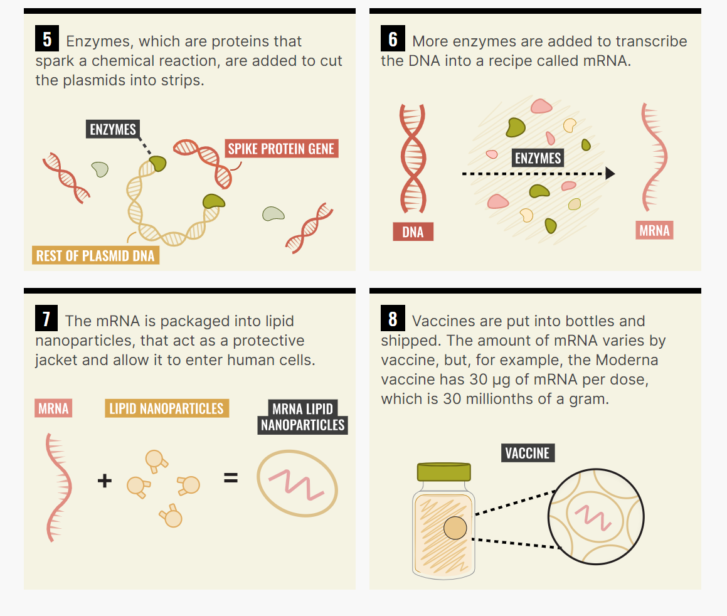

Here’s an extremely simplified recipe for an mRNA vaccine for coronavirus.

Start with the DNA sequence for the spike protein — that’s the highly recognizable bits that stick out from the virus’s central orb — because that’s the part the virus uses to infect you. Then, get some E. coli and use it to make a whole bunch of DNA. E. coli has a pretty fast growth rate — it takes about 20 minutes to double.

From there, use enzymes to reverse engineer little recipes for that DNA — that’s what mRNA is. Last is arguably the trickiest bit: inserting the bits of mRNA into the lipid nanoparticles — little safety bubbles that transport the virus into your body.

In theory, this is all easy. In practice, it’s very, very difficult and both BioNTech and Moderna have slightly different recipes and have relied on different technology, ingredients and suppliers, the intimate details of which are not publicly available.

Using, in part, the snippets of information that are publicly available, Afrigen got to work in the fall of 2021, collaborating with nearby Wits University. As of fall 2021, it had gotten as far as making the mRNA.

The next step is try to replicate that on a small scale in their lab here.

Minus the recipe, the Afrigen team has teamed up with advisers who have expertise in making vaccines more generally. “So any support and added know-how is helpful. And so we’ve had great support from many other suppliers, actually,” Ferres says, pausing in a room lined with dozens of electric outlets for the machinery that will eventually fill the space.

But the project has raised questions about who gets to own new technology and how that equation shifts during a pandemic, when the technology in question could change lives. Terblanche has said that if Moderna was willing to share its technology Afrigen would be operational within a year. But if not, it’s going to take closer to three.

Moderna has been entangled in a dispute with the American government over who most deserves the credit for its vaccine — a question with major implications for who can license the technology and potentially share it with others. The U.S. National Insititutes of Health, which collaborated with the company for four years, argues that three of its own scientists deserved to be on the patent.

In November 2021, Moderna released a statement saying that that, despite the public funding that went into its vaccines, it “(did) not agree” that American government scientists co-invented the company’s shot. It argued that the critical ingredient — the mRNA sequence — was selected by its own experts, and them alone.

The fight appeared headed for court until Moderna paused it in December amidst the rise of Omicron.

Moderna did not respond to questions about Afrigen specifically, but referred the Star to a letter that CEO Stephane Bancel sent to company shareholders at the end of 2021 that referenced the company’s “deep sense of responsibility” to “deliver on the promise of mRNA science for people around the world.”

It also points out that Moderna has said it would not enforce its intellectual property during the pandemic. (A timeframe which some activists have said is too vague to be useful.)

The letter details Moderna’s own plans for bolstering global access to vaccine, including an agreement to supply as many as 650 million doses to COVAX at its lowest tiered price, to be delivered by the end of 2022. It has inked a memorandum of understanding with the African Union to supply as many as 110 million doses to low income-countries on the continent.

Moderna has also announced it is building its own “state-of-the-art mRNA facility” — in Africa.

At this point, Afrigen’s plan is to use Moderna’s dose — or an approximate version — to learn how to make a vaccine, but then develop a version that is its own.

Terblanche herself bristles at the idea that they are encroaching on protected technology. “That is a very emotional debate, you know. And so I know my history, and where I come from, is I value knowledge. And I value the creators of knowledge.”

“I’m not judging Moderna,” Terblanche says. “I don’t want to negotiate with them in the press. I don’t want to even have a conversation with them in the press. But I think this is going to be a challenge for them. I think this is going to be a tough one for the company.”

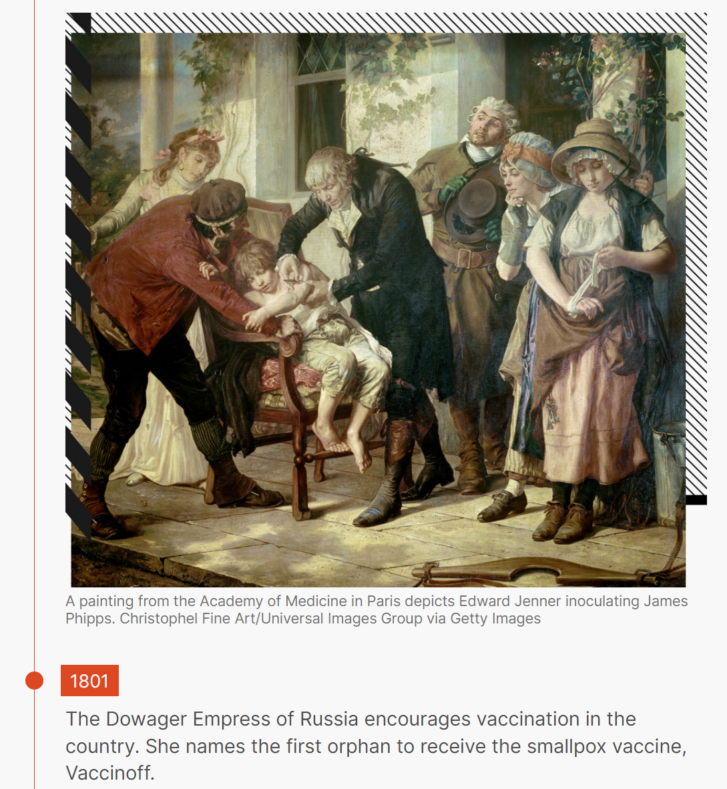

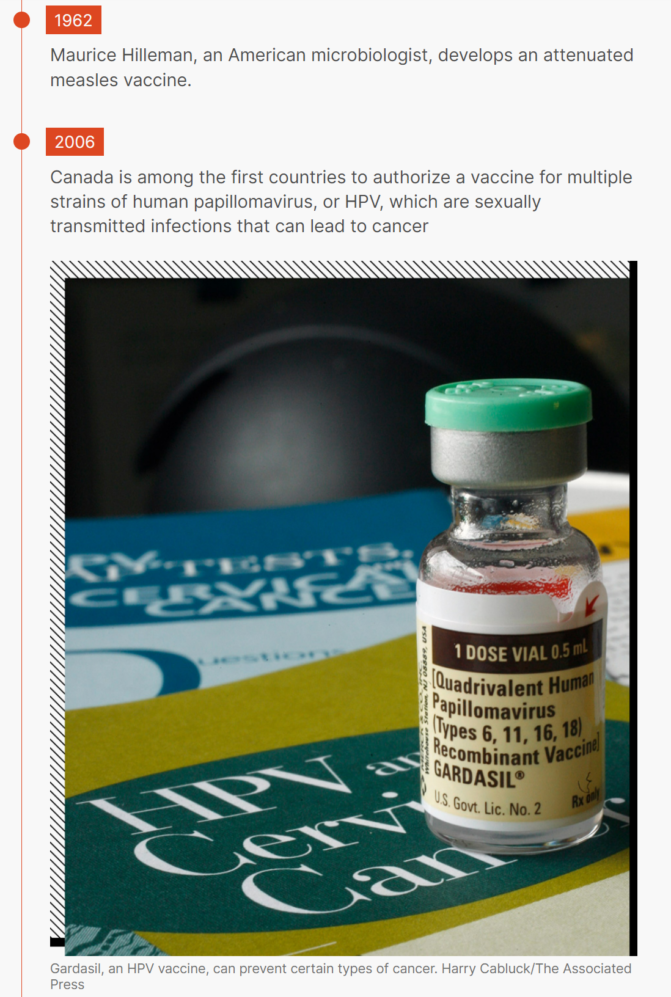

Vaccines reliably make the list of humanity’s greatest medical achievements. Shots that ward off diseases that have haunted humanity for hundreds of years — polio, measles, smallpox — mean most humans no longer live their lives against the seasonal backdrop of sickness.

But as a money-maker, vaccines have significantly less allure. Developing a new vaccine can cost north of a billion dollars, and, despite the astounding success of the current crop of COVID vaccines, most of them fail.

In order to make them economically viable, they’re made by a relatively small number of companies, in a small number of facilities around the world. A global crisis forces vaccine makers to divert attention from their core business of flu vaccines and routine childhood shots — a risky move, according to an article published in Health Security in 2020.

Companies rushed into vaccine development when the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency in response to an Ebola outbreak in 2014, and again for Zika in 2016. Both times the disease petered out before the vaccine candidates were even out of trials. COVID has been rather different. That scientists were able to develop an effective vaccine — more than one, in fact — so quickly was a huge achievement that has saved countless lives around the world. It’s been a profitable achievement. According to Marketwatch, a financial news site, Moderna and Pfizer reported a combined $17.2 billion in the first half of 2021, a windfall that was just the beginning, as global export and sales of booster shots increase.

The exact details of who has paid for shots — and how much — has remained murky, as many of those contracts have been kept secret. Canadian’s now-former procurement minister, Anita Anand, has said that discretion was required, given the competitiveness of negotiations.

There’s no question that the science has been cutting edge, but the money has come from taxpayers. The U.S. government poured somewhere in the neighbourhood of $2.5 billion into Moderna alone.

So to whom should that technology belong?

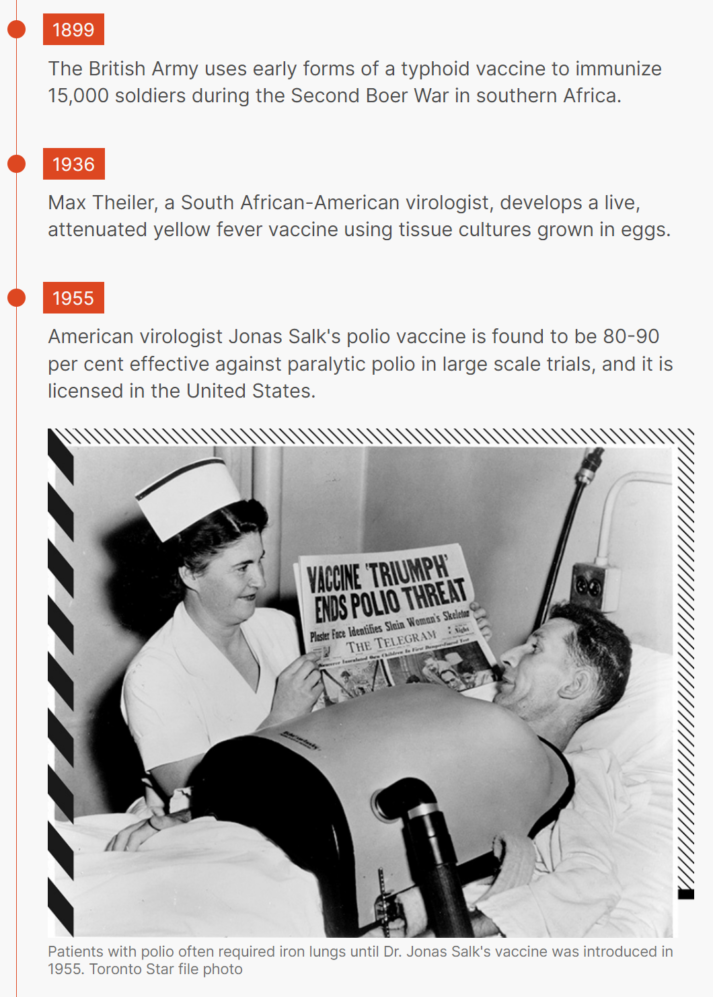

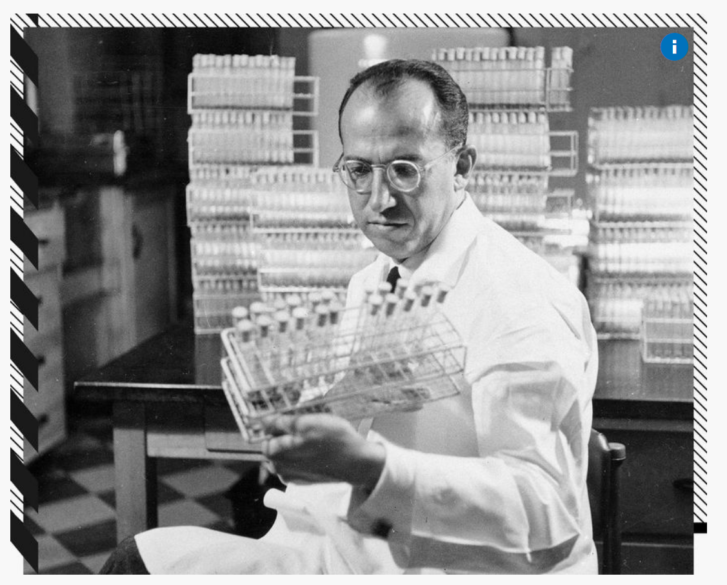

During a TV interview in 1955, Jonas Salk, the bespectacled American doctor who invented the first polio vaccine, was famously asked who owned the patent for his new shot.

“Well, the people, I would say,” he said. “There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

Salk didn’t seek to make any profit off his vaccine, meaning it could be manufactured and distributed around the world by anyone who wanted to make it.

His vaccine would go on to play a critical role in nearly eradicating a public-health scourge known by some as “the crippler,” a disease that once killed thousands of children every year and paralyzed many more.

In the more than half a century since, his willingness to let anyone make his vaccine has been used as an example of drug development done in the public good.

Patents occupy an awkward space in the history of drug-making. Many who make drugs say they’re a hard-earned pat on the back for the researchers or companies that can spend years toiling away on new drugs.

Others counter that in emergencies they hold back distribution of potentially life-saving medicine. Not to mention, vaccines such as Salk’s were made possible because of public money, donations and large-scale trials on schoolchildren.

Now those arguments are being played on a massive stage, as a virus approaches; buffeting a global vaccine rollout that will dwarf even the polio campaign. The key question: Who owns the recipe for a new vaccine, and as the world burns, should they share it?

On a hot summer morning in Cape Town, a bustling port city in the shadow of Table Mountain, Fatima Hassan has set up a makeshift desk at a table on the shady side of a cafe in a lush green park.

Hassan is one of the loudest voices for vaccine equity in the country. A lawyer and activist, she’s a veteran of the fight for health care during the height of the HIV epidemic, she’s spent the pandemic focused on one question: Why, given how much public money has been poured into the COVID vaccines, are governments at the whims of pharmaceutical companies?

“So sorry to sound cynical but, I mean, I wrote about this in April 2020,” she sighs.

Early on, she was optimistic about all the chatter from other countries about everyone being in this together, and the need to combat the pandemic with one voice.

Still, weighted with the memory of the fight for access to HIV drugs, she wrote, early on, about what needed to be done.

“Do not rely on promises, do not rely on charities. If we don’t address the systemic issues around equity, we’re going to have a situation where Africa is last in line,” she recalls warning.

“And what do we have? Africa is last in line.”

But Hassan is less worried about things such as vaccine donations; arguably a Band-Aid solution that hinges on the benevolence of richer nations. She’s concerned with the issue of intellectual property.

Here’s another spot where the history comes into play. In the period after the Second World War, most of the major countries involved were just trying to rebuild their economies after the devastation. In order to boost the post-war economy, about a dozen countries came together to try to grease the wheels of international trade.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade came into effect in 1948. One of its major focuses was eliminating tariffs, and making sure that all the countries were generally treated as equals. If you wanted to sell your family’s signature tomato sauce overseas, it suddenly became a whole lot easier.

In 1995, that was rolled into the World Trade Organization, and most of the world is now signed up. At the same time, it added a new clause called the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS, which requires countries to protect intellectual property rights. We’re talking everything from if you found a new plant to a trade secret. The upside to this is that it created a financial incentive for companies or inventors to create new products. Suddenly, other countries had to make sure no one stole your family’s tomato sauce recipe.

Built into it is this idea that you can waive it for short periods of time, under certain circumstances. Think about a waiver as temporary get-out-of-jail-free card — if granted, one of your competitors can make your tomato sauce, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

That’s bad news for you, but good news for people who really, really need tomato sauce. You lose temporarily control of your product, but you might still get to charge royalties, so you’re making something.

Enter the vaccines. Hassan has argued that countries should temporarily pause intellectual property rights on the new vaccines, in a move otherwise known as a TRIPS waiver.

The push for this first came from the South African government in the fall of 2020. Since then, it’s been supported by more than 100 countries. But the WTO operates on a consensus basis, and standing firmly in the way are the EU and Britain, which both have large pharmaceutical manufacturing centres.

“One of the reasons for this one is, to be blunt, money,” says Adam Houston, a lawyer specializing in health and human rights who has tracked Canada’s movements on TRIPS closely. Both Pfizer and Moderna have made billions off their vaccines, but it’s not even just about the money, Houston argues.

“A piece for vaccines is that it is the underlying platform that is more valuable,” he says, referring to the relatively new way of using mRNA. “Over the longer term, they’re already talking about using it for all kinds of other diseases.”

Canada has been noncommittal about its position, and despite the country’s relatively small sphere of influence, Hassan has harsh words of the role it has — or hasn’t — played.

“I think the irony of this is that the Canadian health-care system is one that understood that you’ve got to have affordable health care, you’ve got to have affordable access to medicines,” she says. “Of all the countries in the world, (you’d think) Canada, given its health system would understand why in a pandemic, a life-saving intervention, whether it’s a vaccine or a treatment, should be available to everyone.”

Canada has, historically, been a leader in this approach.

There have long been instances in which countries created what’s called a compulsory licence, whereby they allow a company to manufacture a product or drug even though it’s protected by a patent, sometimes because it was an emergency or there was no other way to get a badly needed medicine.

Canada granted a slew of compulsory licences starting in the 1960s, Houston says, but due to a variety of trade pressures, started scaling back by the 1980s. The only time the government had really considered reviving the practice was after 9/11, he says, when they debated making Ciprofloxacin, a drug you take when you’ve been exposed to anthrax.

Even when TRIPS was created, there was a trap door built into it that allowed countries to manufacture drugs in a “national emergency” or “other circumstances of extreme urgency.”

In 2001, an update known as the Doha Declaration even allowed countries to do this for other nations that wouldn’t otherwise be able to make essential drugs on their own.

That’s how, in 2007, Canada gave Apotex, its largest pharmaceutical company, the green light to start manufacturing generic versions of three HIV drugs — despite not having permission from the drug developers — and sent them to Rwanda. The move was a hand up for the small central African country. At the time, 13 years past a genocide, only a quarter of the roughly quarter million people infected with HIV were getting treatment.

Using this argument, a Canadian company called Biolyse has also spent months trying to get the federal government to grant a compulsory licence for vaccines so it could manufacture doses for Bolivia — but, so far, no dice.

The irony, Houston points out, is that outside of Canada’s use of compulsory licensing, these exceptions don’t get used that much.

“TRIPS on paper says all kinds of nice things about measures for protecting public health and so on. But one of the big issues globally is that, in practice, when you’re Brazil or South Africa and you’re trying to use flexibilities like compulsory licences, you will still have pharmaceutical companies going after you, you will still face pressure from powerful countries that don’t like you doing this,” he says.

That’s why a growing number of countries are now insistent on a waiver — to have the ability to make vaccines formalized, removing the “looking over your shoulder” factor, as Houston puts it.

So where is Canada?

So far, this country has largely sat on the fence. In May, Mary Ng, the minister of small business, export promotion and international trade, released a statement saying the government “firmly believes” in protecting intellectual property, and says that industry played an “integral role” in developing vaccines. Still, the government “is ready to discuss proposals” for a waiver on vaccines.

In an interview with the Star in January, Ng’s position hasn’t budged much. Ng insists that intellectual property remains only one piece in getting vaccines out to the world, and that Canada is very much part of conversations about other trade issues needed to produce vaccines, such as manufacturing capacity, supply chains and export controls.

“I think that it’s important to be clear, so that so that Canada’s position is clear,” she said.

“We absolutely, fully support an outcome that ensures vaccines are accessible to people in the world. We absolutely support that. We also actually support a multilateral solution on TRIPS, and we very much have been at the table.”

What remains unclear is whether, when push comes to shove, Canada would support the waiver.

The oldest inhabitants of South Africa are known collectively as the San, a term that applies to a very diverse mix of people, but most of whom fed themselves by trapping or hunting using bows and arrows, tips poisoned with toxins from snakes or certain types of beetles.

On long trips through the desert, some would chew on the bitter flesh of what’s now known as hoodia. They’d strip the needles off the cactuslike plant and chew the soft flesh underneath, which one early botanist reported as tasting like licorice, to suppress their hunger and thirst while tracking prey through the sand.

They shared this trick with a European researcher, either Dutch or German, an botanist or an anthropologist, depending on whom you ask, back in the 1930s. The information was published, though it would linger there, gathering dust in the public sphere, until decades later, when the South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research took notice. In the years since, the market for diet drugs had swelled to be worth billions of dollars.

Perhaps, scientists thought, what has worked for hunters for centuries could also help those struggling with obesity. In 1995, the council filed a patent in South Africa for the use of the active components in the plant. A few years later, they licensed it to a British company called Phytopharm, which specialized in medicines using plants. A year after that, drug giant Pfizer got on board, with the goal of developing it further. A clinical trial, involving 18 overweight but otherwise healthy men, got underway. At some point, Pfizer dropped out, but Unilever signed on, in part, because it wanted to add the eventual compound to its line of SlimFast shakes.

All was going swimmingly, except for the fairly significant detail that no one had told the San about any of this.

In a 2009 book about Indigenous peoples and consent, authors Rachel Wynberg and Roger Chennels tell the story of what happened next.

It’s impossible to untangle the case from the history of the San. Like Indigenous peoples around the world, they’d been marginalized and discriminated against by colonial setters. Settlers had even hunted them in legally sanctioned raids.

At the time, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research argued it was difficult to tell who the idea had originally belonged to, and it didn’t want to get the San’s people’s hopes up by getting them involved with the new research. (Memorably, however, a Phytopharm executive was quoted in a newspaper as saying that he was told the San “no long existed,” despite the San numbering about 100,000 across three countries.)

In 2001, a South African NGO called Biowatch flagged the issue to international media, who were quick to pick up the story of an potentially exploitative deal. The resulting uproar set the stage for negotiations between the CSIR and the San. A memorandum of understanding and profit sharing agreement was finally signed — one of the world’s first.

One of the people who helped create that agreement is one Petro Terblanche.

Two decades later, it could be argued that the shoe is on the other foot, as she tries to figure out how to make a version of the Moderna vaccine, despite the company’s unwillingness to co-operate — though that’s something she pushes back on.

“For me, (hoodia) is a beautiful case study where Indigenous knowledge and tacit knowledge developed over years, hundreds of years, and hard science came together and started a journey, which then parted because the hard science brought evidence that maybe this is not as safe as it looks.”

The irony of that, Terblanche points out, is that you can still buy hoodia — a quick google search turns up a colourful menu of pills and supplements — but because the patent deal to develop it into medicine never went anywhere, the San are not making any money. Done right, intellectual property can make sure that the interests of creators are served while their technology is made available to a wider public.

So apart from the fact that it would be illegal, Terblanche insists her team would never go to market with a knock-off Moderna vaccine because she believes it to be morally wrong. Still, there’s something about Moderna taking public money while refusing to co-operate with others that rubs her the wrong way.

“We have to incentivize inventors. I feel very strong about that. There has to be something that goes back materially to the inventors other than just earning their salaries,” she says.

“So I’m not a socialist,” she adds. “But greed is a deadly sin.”

In January, the company reached a major milestone — announcing it had produced the first vaccine, based on the Moderna sequence — with the goal of testing it in humans before the end of the year. In February, the World Health Organization named the first countries, including Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa and Tunisia, that will receive what’s called a tech transfer, and learn from what Afrigen is doing.

For its part, Moderna argues that soon, supply won’t even be an issue.

In a blog post from last October, Bancel, the Moderna CEO, says that all vaccine manufacturers produced roughly 12.5 billion doses in 2021 and points to predictions that that number will be hit again in 2022, but by June.

While he says the company has made proposals to the U.S. government and to COVAX to potentially provide “significantly” more doses this year, supply will outstrip demand in the coming months, and the conversation will need to turn to administering those shots.

“We believe that in the coming months, there will be enough COVID-19 vaccine doses for any adult in the world who wants one.”

Emile Hendricks’ career journey began while he was watching TV.

The child of two parents who didn’t finish high school, he says science was not a thing he ever considered. Until, that is, he started watching the Big Bang Theory, a TV show in which the main characters, Sheldon and Leonard, live in a spacious apartment and work as scientists. Then, sometime around Season 3, their friend, a microbiologist named Bernadette, is headhunted by a pharmaceutical company and announces she is going to make a “buttload” of money.

“I was like, ‘I want that. I want to make a bunch of money,’” Hendricks says, laughing as he perches on a stool, draped in a long white lab coat. “And that’s when I decided I’m going to do microbiology.”

(Spoiler: scientists do not in fact typically make tons of money. “That was a bit of a misnomer,” Hendrick concedes.)

Still, he beams when asked about the project that he’s fallen into, almost by accident. He was first hired as an intern, but managed to stay on for his first real job.

Now his day involves things like making sure everything in the labs are in the right place and machines are working the way they should be.

“So, a typical day for me, is just science-y things,” Hendricks says, with the loud laugh of someone who can’t quite believe his luck at landing a job at Afrigen.

His good humour gives way to a serious thoughtfulness about what he’s doing here.

“It is an honour to be a part of something like this, because every scientist’s dream is doing something that extends way beyond yourself,” he says.

It was heartbreaking to watch those first doses roll out, and then be snapped up by wealthy countries, he says.

“One thing we’ve noticed, or that has been highlighted during the COVID pandemic, is how much Africa is on its own when it comes to these emergencies,” he says.

“We have been so heavily reliant upon these big countries, big companies to save us. And it has come to show that when push comes to shove, we will be the ones who are shoved.”

Article From: The Star

Author: Alex Boyd