In December before the Surrey Board of Trade, Deputy Bank of Canada Governor Toni Gravelle spoke of how our economy has come a long way since the pandemic struck and essentially shut the economy down. We are “well down the road to a full recovery,” he said. “But we are still feeling the impacts of the pandemic.”

Gravelle outlined the bank’s top two concerns were supply shortages and the elevated rate of inflation.

Whether it be food, gas, or housing prices, inflation is becoming a global concern during the pandemic. In a recent Nanos survey, inflation and cost of living were listed as the top source of anxiety. In fact, the poll found that Canadians are nearly nine times (87%) more likely to say they’re worried more about higher prices for everyday goods rather than higher interest rates (10%).

Ahead of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) numbers due to be released on Jan. 19, CTVNews.ca spoke with experts and included a few graphs below to explain why inflation is on top of everyone’s mind, how the pandemic has impacted it, and how Canada compares on that front with G7 nations.

What is inflation and why does it matter?

The consumer price index, better known as CPI, is the most common system to gauge inflation. It measures the cost of living by looking at the prices of goods and services that people typically buy such as food, housing, transportation, furniture, clothing, recreation, and other items.

Like most central banks, the Bank of Canada monitors “core inflation” that focuses on the underlying trend of inflation, looking through the short-term fluctuations or temporary shifts in the total CPI.

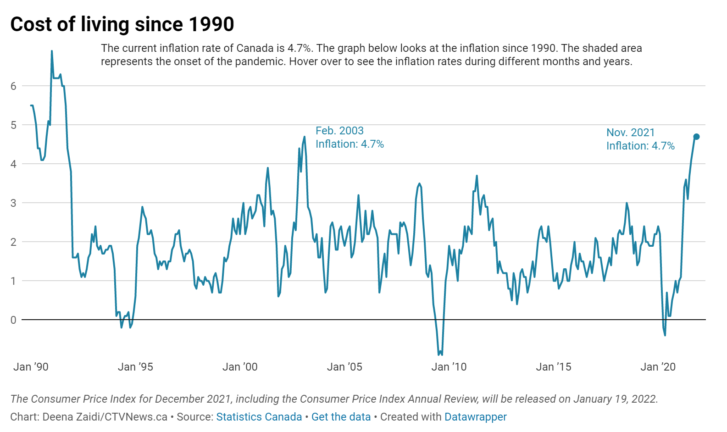

The current inflation is 4.7 per cent, significantly higher than the top of the Bank’s inflation-control range. The Bank of Canada aims to keep inflation at the 2 per cent mid-point of an inflation-control target range of 1 to 3 per cent. Low and stable inflation contributes to sustainable economic growth. The balance between the demand and the economy’s production capacity determines inflation.

The Bank becomes concerned if the inflation rises above or falls below the 2 per cent target. A high inflation reduces the purchasing power of a household or an individual and can significantly impact household budgets. High prices can change our shopping habits, investments, travel, transport, and even medical expenses.

Negative rates often create a period of deflation, which means a decline in the prices of goods and services, giving more purchasing power to consumers. While falling prices sound like a good thing, a persistent decline in prices can negatively impact an economy. The effect is negative for debtors who have failing businesses or have declining income since the real value of debt payments for them can increase. In the same way, if prices and income fall, tax revenues can fall and impact government spending. One major example of sustained deflation in Canada was in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

How is inflation monitored?

The Bank of Canada conducts monetary policies to ensure the inflation target is maintained. It usually takes about six to eight quarters to see the impact of the tools used to combat inflation and that’s one reason that monetary policies are always forward-looking.

The Bank relies on different tools to control the money supply in the market such as large asset purchases (quantitative easing and credit easing), funding for credit measures, and negative policy rates.

To stimulate the economy and encourage borrowing, spending, and investment, the central bank can resort to an unconventional tool known as the negative policy rate where it sets its target nominal interest rate to less than zero per cent. In the light of the 2008 subprime mortgage crises, several nations such as Japan and Europe had resorted to zero policy rates.

However, pushing rates to below zero impacts short-term interest rates and can eventually affect mortgages, lines of credit, and other, longer-term interest rates that matter to average Canadians. The Bank of Canada uses other tools such as quantitative easing to support low policy rates. Quantitative easing is when central banks pay for bond purchases with settlement balances (not bank notes). The Bank buys bonds that have already been sold by the government to banks and other financial institutions. In credit easing, the Bank can also buy corporate bonds from financial institutions, which can support the economy, making it cheaper for companies to invest and create more jobs.

All these policies indirectly affect the total demand for Canadian goods and services.

Impact of the pandemic on inflation

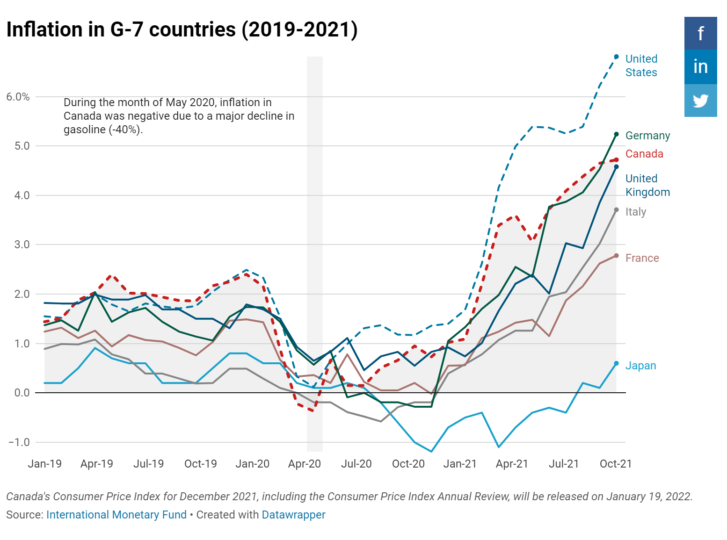

With the new variants, the pandemic has taken an unprecedented turn. When compared to other advanced economies, Canada’s inflation is on the lower end. The U.S. has recorded an inflation rate of 7 per cent, the highest since 1982. Leading contributors to the U.S. inflation were housing, cars, and trucks. According to a survey of 900 global CEOs, rising inflation, labor shortages, supply chain disruptions, and changing consumer behaviors were top worries.

Due to factors such as rising demand for oil and gas, the shortage of many goods, supply shortages, the cost of living in the U.K. rose by 5.1 per cent, the highest in 10 years. A recent survey by the British Chambers of Commerce said that 58 per cent of firms expected their prices to increase in the next three months, the highest on record. Of those surveyed, 66 per cent of businesses cited inflation as a concern.

Energy prices and supply rate disruptions have pushed inflation in Europe’s second-largest economy, France as well.

One of the biggest impacts of the pandemic has been on the supply chain, which is pushing inflation globally and in Canada as well, driving up everything from cars and furniture to food and shelter.

“Supply chain networks have been disrupted globally,” Sal Guatieri, senior economist and director at BMO Capital Markets told CTVNews.ca on Monday.

He said factories are getting closed either due to a shortage of staff because people are sick or under quarantine. This indirectly impacts the steady supply of raw materials that are used in the manufacturing process globally.

Guatieri said at the same time the cost of freight across oceans has increased due to the shortage of truck drivers. So all these costs are getting passed on to the consumers. But aside from the supply chain disruptions, inflation is also impacted by several other factors such as food prices, gasoline prices, house prices, homeowner replacement costs, energy prices, and motor vehicles costs. In 2021, global food prices rose ‘sharply’, according to a recent report by United Nations (UN). The agency’s Food Price Index, which tracks monthly changes in international prices showed a 28% increase over 2020. The reason for this jump was the high cost of inputs, ongoing pandemic, and volatile climatic conditions.

Guatieri said a source of upward pressure on inflation has been a rebound in some of the hard-hit service areas such as travel and car prices. Hotel costs and airfares have climbed in the past year and could be a source of upward pressure on inflation. Car prices have been impacted by chip shortages, resulting in the highest costs and shortage of new vehicles. Gualtieri said homeowner displacements costs could be a big source in driving up inflation. With house prices accelerating, more people could be pushed into the rental market because they can’t afford a home, he added.

Article From: CTV news

Author: Deena Zaidi