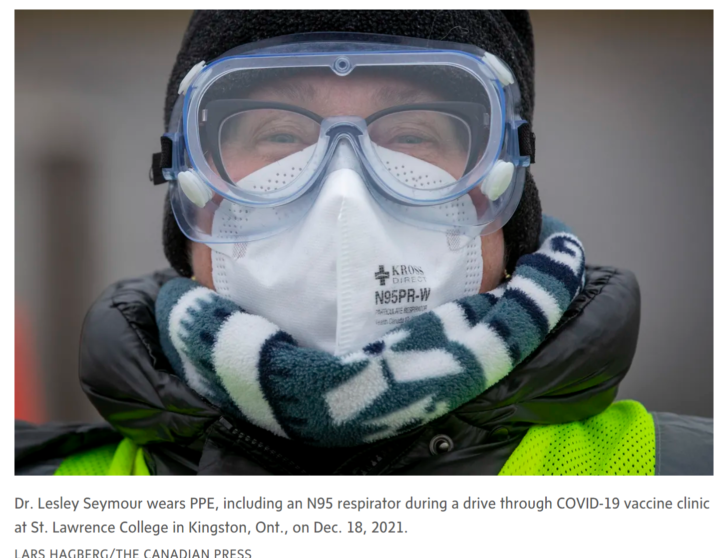

Ontario will offer N95 masks to school staff when classes resume next week, a move that comes after unions and parents have long called for the measure. The decision, amid a surge of cases because of the highly infectious Omicron variant, is expected to stoke debate about who should be offered the higher-quality equipment, which could more effectively cut COVID-19 transmission.

In general, N95 masks are already used by health care workers in high-risk medical settings, particularly when COVID-19 patients undergo aerosol-generating procedures such as intubations or chest compressions.

But, in many jurisdictions across Canada, N95 masks are not required or provided to health care workers in contact with people suspected to have COVID-19. Organizations and individuals have called for a move to masks with better filtering capabilities, owing to the recent spike in cases and as research has clarified that aerosol transmission is, in addition to droplets, a key way SARS-CoV-2 is spread.

This debate has existed longer than the Omicron variant, however. The Ontario Nurses’ Association took the Ontario government to court last year in an effort to mandatethe use of N95 masks. The case was eventually dismissed, with a three-judge panel ruling that nurses were already able to request N95s as they saw fit. In Quebec, a judge ruled early this year that nurses coming into contact with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases should wear N95 masks. And, last week, Alberta Health Services and the United Nurses of Alberta announced a new agreement that will increase health care workers’ access to the masks.

The calls to move to N95-type masks – which are able to filter 95 per cent of air particles beyond a certain size – are complicated by the fact that the science, experts say, is still not settled on whether N95s provide significantly better protection than surgical masks.

“The reality is we don’t have good data yet,” said Roger Chou, a clinical epidemiologist at Oregon Health & Science University. Dr. Chou has tracked studies looking at the effectiveness of different forms of masking in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection since the fall of 2020.

While some studies have suggested that N95 masks offer much better protection than surgical masks in health care settings, others have been less definitive – an issue, Dr. Chou said, that comes down to the difficulty in conducting research that compares the two types of masks.

“It’s really difficult to control for all the factors that can cause infection,” he said.

When it comes to mask policies in the community, the picture becomes even murkier.

In Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic, governments have mandated community use of N95-like masks. But those areas haven’t seen marked reductions in infection rates, according to Dr. Chou. “There’s not compelling data at this point,” he noted.

Still, Dr. Chou isn’t opposed to the use of N95s. “In my opinion, the benefits of N95s are probably there,” he said.

Lynora Saxinger, an infectious-diseases specialist at the University of Alberta, strikes a balance between the possible benefits of N95s and their downsides, given they are more difficult to wear than surgical masks.

While the tight-fitting N95s do a better job of filtering particles than regular masks, they are less comfortable and must be fit-tested to each person, she said. If they aren’t properly adjusted to form a seal, air will instead be forced around the sides and into the mask.

N95s are also not suitable for people with facial hair intersecting the mask’s edges, and child-sized masks can be hard to come by. They may also not work as advertised. Some manufacturers’ masks have been found to perform dramatically better – or worse – than others, and there are no standardized measurements of mask quality that producers can be held to.

That said, Dr. Saxinger says we have arrived at a point in the pandemicwhere health care workers outside of high-risk settings are being told they can keep wearing their surgical masks, or upgrade to N95s depending on their preference.

“I think that’s okay, honestly,” she said.

In the coming months, this guidance might yet change. Dr. Saxinger said she is awaiting the results of a major clinical trial, which could definitively answer whether N95 masks reduce the odds of infection for health care workers compared to regular surgical masks.

The risk calculus is different in an educational setting, Dr. Saxinger said, given that N95 masks are more expensive and difficult to procure.

“There are going to be people saying, ‘You’re not a good parent unless you get N95 masks for your kids.’ I’m sorry, but that’s really unfair,” she said. “That’s not a very equitable thing to do.”

Vicki McKenna, president of the Ontario Nurses’ Association, said that the mask supply concerns from the first few months of the pandemic, when some administrators took to rationing their N95s, are long gone. In health care settings, she said, “there is no issue with supply in this province.”

Yet some of the nurses and health care workers she represents are still unable to access N95s, particularly in long-term care homes or in scenarios where a person’s COVID-19 status is unclear.

“Think about emergency departments, for instance, where people just come in the door,” she said. “That’s why the precautionary principle and erring on the side of caution is necessary. If nurses are working with presumed, confirmed or possible COVID-19, they should be wearing N95s,” she said. “Full stop.”

Article From: Globe and Mail

Author: TOM CARDOSO