The Salish author’s body of work is a tribute to the power of storytelling.

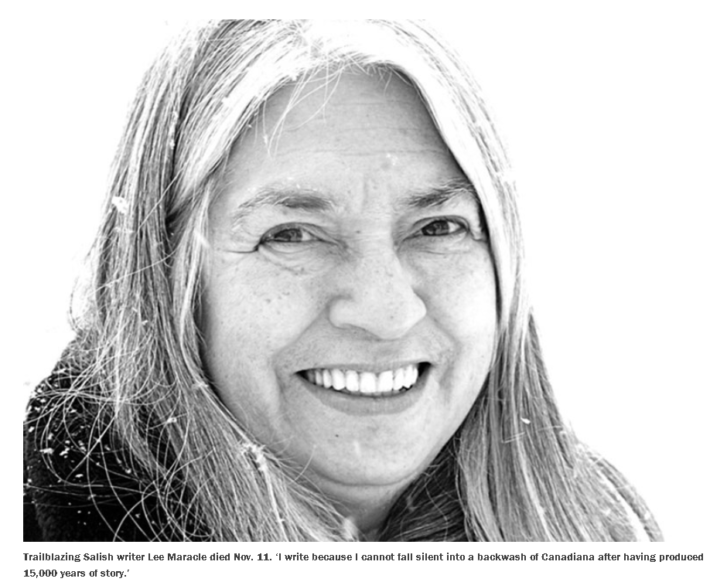

On Nov. 11, legendary Salish author Lee Maracle passed into the next life. The outpouring of grief, stories, memories and tributes that followed demonstrated her profound impact on the world, particularly Indigenous writers.

Maracle was born in what we call North Vancouver in 1950, on the traditional territories of her ancestors, 10 years before Indigenous people were granted the right to vote in Canada. She often observed that Indigenous storytelling was a tradition with more than 15,000 years of history, and yet she grew up in a country that published no Indigenous authors.

Her first work was an autobiographical novel, Bobbi Lee Indian Rebel, which was published in 1975, just a few years after Maria Campbell’s memoir Halfbreed. The two comprised the entire canon of published non-fiction by Indigenous authors in Canada at the time. Bobbi Lee was a work of oral storytelling: Maracle recorded it aloud, and it was transcribed by her mentor and SFU professor Don Barnett, who also published it through his Liberation Support Movement press.

In one famous anecdote, Maracle took the manuscript for Bobbi Lee to publishers, who rejected it, telling her “Indians can’t read or write.” She collected signatures from more than 3,500 Indigenous people who said they would buy the book. Many of the people she met along the way were illiterate, and in response she founded literacy programs for Indigenous people.

It’s one of countless stories about Maracle that demonstrates her innate understanding of the value and power of her work. In Memory Serves, a 2015 collection of her oratories, she writes, “The value of resistance is the reclaiming of the sacred and significant self. By using story and poetry I move from the empowerment of my self to the empowerment of every person who sees himself or herself in the story while reading the book.”The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

Maracle was an activist, teacher, poet, feminist, mother, grandmother and scholar. Throughout her life she was an ally to queer folks and other oppressed peoples; she saw clearly that the degradation of any person based on their identity was a colonial invention, and she rejected it. As writer Billy-Ray Belcourt wrote on Twitter, “[H]ow fortunate are we as an Indigenous literary community that one of our first writers was so deeply committed to feminist living and queer and two-spirit solidarity.”

Her work defies easy categorization because she drew from her Salish storytelling traditions, mastering western modes of storytelling and narrative in order to subvert them. She published non-fiction, oratories, novels, poems. All of her works are defined by her ferocious intelligence, her profound empathy, her cultural traditions, and her belief in the transformative power of storytelling. In her 2014 novel Celia’s Song, her last published work of fiction, she wrote “This story deserves to be told; all stories do. Even the waves of the sea tell a story that deserves to be read. The stories that really need to be told are those that shake the very soul of you.”

By the end of her life, she was recognized and embraced by the Canadian literary scene, but she had to fight to get there. In 1988, the Vancouver Writers Festival declined her request to launch her new book I Am Woman: A Native Perspective on Sociology and Feminism at the festival; she leapt on stage, seized a mic and read anyway.

Even as she acquired awards and accolades, she never became complacent. She continued to fight for Indigenous sovereignty and reject the hypocrisy of a nation more interested in talking about reconciliation than enacting it. She was a fierce critic of appropriation, indifference, ignorance, and all the other subtler methods of colonial violence that continue to oppress Indigenous people. She made readers and listeners confront their complicity; she refused to be silent. Perhaps this is why so many obituaries have referred to her as “combative” or “aggressive”; I think it’s more accurate to say she was a tireless critic of injustice, puncturing the national self-image of Canadians as nice people.

In her 2017 collection My Conversations with Canadians, she wrote, “I have seen many of you at book launches, panels, conferences, gatherings of all sorts, including protests against some injustice or other of which there are so many. Not a single Canadian has ever approached me to say: ‘Why are there so many injustices committed against Indigenous people?’ or ‘Why is there not a strong movement of support for justice and sovereignty for Indigenous people’s sovereignty movement in Canada?’ Canadians love causes, but they love the causes that are far away — out of their backyard, so to speak.” Maracle never let them forget that they were in her backyard, and that they owed Indigenous people respect, autonomy and honesty.

But most of all, she wrote for Indigenous people. In her 2018 essay Scent of Burning Cedar, she wrote, “I write because I cannot fall silent into a backwash of Canadiana after having produced 15,000 years of story. I write because I want our youth to know that we have value, we have knowledge, and we have a place in this world. The place we have was carved for us by our ancestors, who loved us so much that they died that we might live.”

Shortly before her death, she gave the annual Margaret Laurence lecture. Maracle’s voice is always her voice: she is honest, unsparing, witty, incisive. I listened to it again while writing this, reflecting on her belief in the story as a means of collective survival. In it she says, “Every word originates in a body. Every word is a call to action, to movement, to being a salutation to the stars, an address to the world, to the skies, the waters, and all our relations. Today, yesterday, tomorrow, no call song can disappear. No word is ever unheard.”

To honour Maracle’s life, read her work; let yourself be transformed by her stories. And read other Indigenous writers too, particularly women. Maracle often said that women are the keepers of culture, of the inner lives of Indigenous people. As she said in her Margaret Laurence lecture, “If you do not read the women, you will not know who we are.”

We are so fortunate that there are so many Indigenous women publishing now, too many to name: Eden Robinson, Alicia Elliott, Terese Marie Mailhot, Lisa Bird-Wilson, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Tanya Talaga, Katherena Vermette, Tanya Tagaq, Cherie Dimaline, Michelle Good, Tracey Lindberg. Maracle dreamed of a world where their stories would be honoured and heard, and then she created it for them. That was her gift to all of us. ![]()

Article From: TheTyee.ca

Author: Michelle Cyca