This post is also available in: 简体中文 繁體中文

Jennifer Hubert jumped at the opportunity to get her COVID-19 vaccine, but she’s not looking forward to having to make the decision about whether to vaccinate her three-year-old son Jackson.

She recognizes the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, but said she also understands her son is at a much lower risk for serious illness than older adults.

“To me it’s not a clear benefit,” she said.

While many parents were overjoyed at the news that Health Canada is considering approval of the first COVID-19 vaccine for kids age five to 11 in Canada, parents like Hubert are feeling more trepidatious, and public health officials said they are going to have a much more nuanced conversation with parents about vaccination than they did with adults.

While 82 per cent of eligible Canadians aged 12 and up are already fully vaccinated, a recent survey by Angus Reid shows only 51 per cent of parents plan to immediately vaccinate their kids when a pediatric dose becomes available.

Of parents with children in the five to 11 year age range, 23 per cent said they would never give their kids a COVID-19 vaccine, 18 per cent said they would wait, and nine per cent said they weren’t sure, according to the survey of 5,011 Canadians between Sept. 29 and Oct. 3, which cannot be assigned a margin of error because online surveys are not considered random samples.

“Most of the research that I’ve seen sort of indicates that parents are more hesitant to vaccinate their kids against COVID than themselves,” said Kate Allen, a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Vaccine Preventable Diseases of the University of Toronto.

There are several reasons parents might pause, she said.

It’s true that children are at a much lower risk of serious outcomes associated with COVID-19, and there have been very rare incidents of mRNA vaccines like Pfizer or Moderna linked to cases of myocarditis, a swelling of the heart muscle.

As of Oct. 1, Health Canada has documented 859 cases associated with the vaccines, which mainly seem to affect people under 40 years old, and people who’ve developed the complication have typically been fine.

“I know it’s rare, I know it’s not deadly, but I also see the risk of severe symptoms from COVID as being rare and not deadly for Jackson,” Hubert said when asked about weighing up the risks and benefits of the vaccine.

But public health experts stress that some children do suffer from rare but serious impacts from COVID-19, which can also cause myocarditis as well as the little-understood impacts of the condition known as long COVID.

They say parents should consider the less tangible benefits of vaccination as well.

“It’s less of a conversation about a direct benefit to them, and more of a community benefit,” Allen said.

The pandemic has taken a heavy toll on children, depriving them of school, time with their peers, extracurriculars _ and their mental health has suffered as a result, said Dr. Vinita Dubey, associate medical officer of health with Toronto Public Health.

“Not one child has been spared from this pandemic. I mean every single child has had to bear a sacrifice because of the pandemic in one way or the other,” Dubey said.

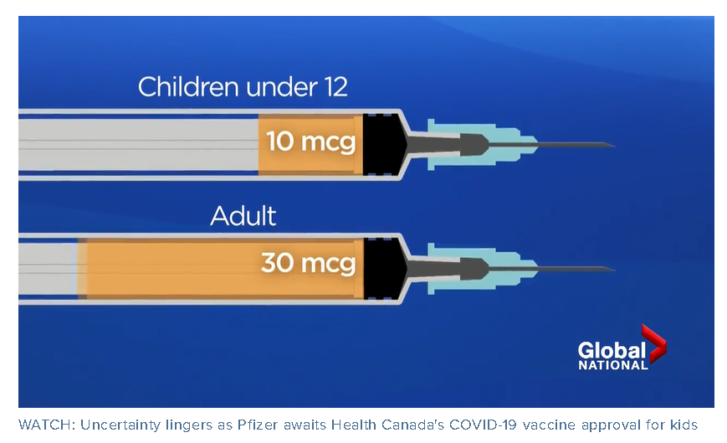

So far Pfizer-BioNtech is the only manufacturer to request approval for its pediatric COVID-19 vaccine and Health Canada is still reviewing the data.

The regulator has promised the review will be thorough, and the vaccine will only be approved for children if the benefits outweigh the potential risks.

Policy-makers know they’re going to have to take parents’ concerns seriously as well.

On a recent tour of the Childrens’ Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke with Dr. Anne Pham-Huy, a pediatric infectious diseases physician.

“Vaccine confidence is going to be the most important part of it this time around,” Pham-Huy said, to which Trudeau agreed.

Dubey has published research on improving parents’ vaccine confidence when it comes to long-established inoculations like mumps and rubella.

While she offered several tips, they mainly come down to building trust. Her research focused on the role of family doctors, but she said during the pandemic anyone can be that trusted sounding board.

“It could be a faith leader, it could be an important family member or friend, someone who you trust, to help guide you to the right sources to make that decision,” she said.

With that in mind, several students from across North America launched a peer-to-peer education program called Students for Herd Immunity to allow kids to have those conversations among themselves.

The public health experts agree, the debate around vaccines has become polarized and open conversations will be the key to addressing parents’ concerns.

“I think one thing to say to parents is you don’t have to make your decision right away,” Dubey said. “I mean for those who are ready to make their decision, but it’s fine but if you have questions, seek the answers.”

Her only advice is to get those answers from a trusted source, and not social media.

Article From: Global news

Author: Laura Osman