Heather MacDougall, the former acting chair of the history department at the University of Waterloo, is an expert on how Canada’s vaccine policy has evolved, but there is one question that she can’t yet answer — whether vaccines for COVID-19 should be compulsory.

“The question of mandatory vaccination with the COVID vaccine is premature because we really need to make sure that COVAX, the international vaccine procurement group, has the supplies that it needs to get to the countries that are really suffering at the moment,” MacDougall said. “And so we also need, obviously, to reach the people that have had no shots or just one shot in this country.

“And frankly, until that’s done it, it seems to me that thinking about making something mandatory and opening that political can of worms is, as I said, premature.”

Historically, the issue of mandatory vaccination in Canada has triggered not only debate but violent protest and even politicization, as was the case in Montreal in the late 1800s in reaction to a compulsory vaccine for smallpox instituted by a mostly English-speaking board of health on the Francophone community.

But it’s been outbreaks like the current pandemic that have helped usher in compulsory policies.

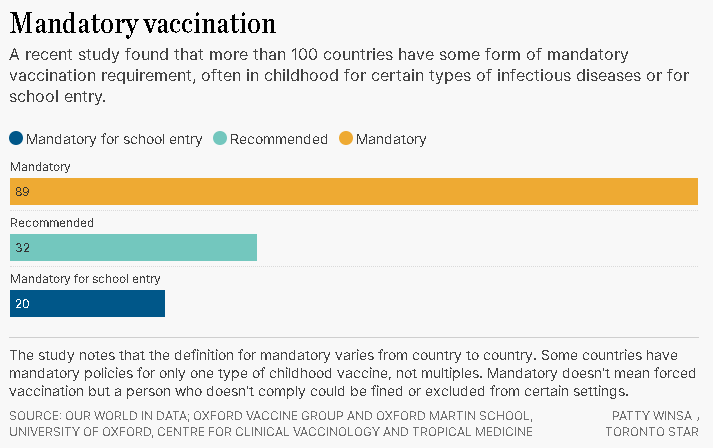

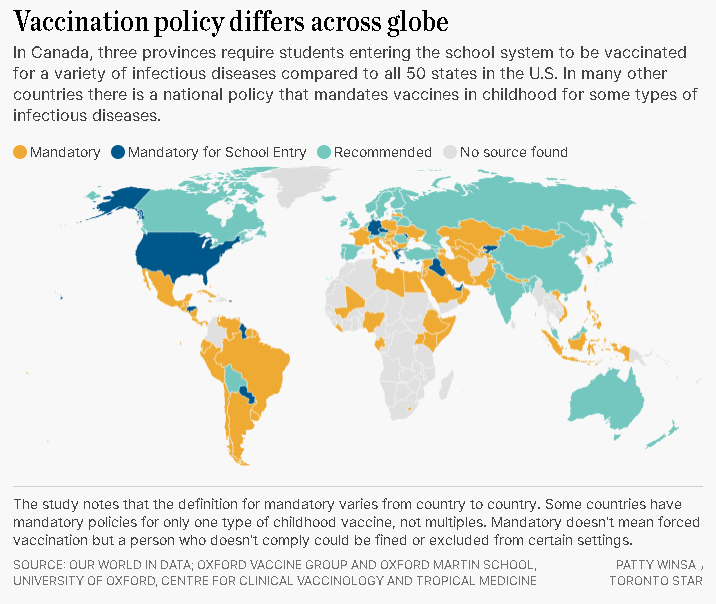

A study by Oxford researchers found that more than 100 countries have some type of mandatory vaccination policy, many of which date back to the 1800s as a reaction to the smallpox epidemic.

However, numerous other countries do not and some mandatory policies were later repealed amid a philosophical debate over compulsion versus co-operation that continues today.

“The early introduction and early pushback (to mandatory vaccination), along with present-day approaches to foster mutual trust and responsibility between citizens and the health authorities, may have contributed to why vaccination is often recommended in many European countries rather than mandated,” the Oxford researchers wrote.

In Canada, the decision has been a provincial one.

In Ontario, it was a measles outbreak in that late ’70s that gave rise to the Immunization of School Pupils act of 1982, which made certain vaccinations compulsory for students entering the public school system.

During the outbreak there were 10,000 measles cases in the province, as many as in the entire U.S., and the provincial Liberal opposition began pressuring the Ontario government to respond, according to a lecture MacDougall gave to Public Health Ontario in 2017.

The result was that in the 1980s Ontario, New Brunswick and Manitoba began using the school system to track and control for measles and other childhood vaccinations.

The introduction of the legislation also gave rise to the modern anti-vaxxer, says MacDougall.

We talk to MacDougall, a medical historian, about how vaccine policy has evolved here.

Q: Why did Ontario, Manitoba and New Brunswick institute various mandatory requirements for immunization in the 1980s and not the rest of Canada?

A: In the 1970s, Canada joined the Pan American Health Organization for the first time, at the beginning of a push to eliminate measles from the Americas, meaning Canada, the U.S., Mexico, Central America and South America and all the Caribbean islands. Various American states had already run campaigns to eliminate measles from 1967 to 1970. The campaigns appeared to be very effective. And then they ran out of money. And measles reappeared. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control began pushing the states to create mandatory immunization requirements for school entry. So as the American states begin to do this, and have a certain amount of success, that led politicians in New Brunswick, Ontario and Manitoba to push their respective governments to consider using the school entry moment, when children are between four and six, as the way to double check to see that they’ve got all their childhood vaccines prior to going to school. As these three provinces start moving in this direction, we are also at the end of the 1970s, patriating the Canadian constitution, coming up with a Charter of Rights and Freedoms. And so there’s a lot of political tension between the western provinces and Ottawa on the National Energy Program as well as the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Q: What is the law that Ontario enacted regarding mandatory vaccinations?

A: The Immunization of School Pupils Act of 1982 stated that children had to be immunized against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles, mumps and polio.(Vaccines for other diseases have since been added.)

Q: Was there an exemption clause at that time?

A: You could be exempt for two specific reasons,medical and religious. And what happened was this led to the emergence of the modern anti-vaxxers.Research that I have done suggests that the traditional anti-smallpox vaccination movements seem to have died out in the 1940s. But with the women’s feminist movement and the environmental movements in the 1970s, along with the thalidomide tragedy in the 1960s and the Dalkon Shield (an IUD that could cause serious infection), and various other medico-scientific failures, there was a lot of questioning of medicine and medical expertise. And in the ’80s, an American TV station broadcast the show “Vaccine Roulette,” which argued that the DPT vaccine had caused all sorts of dreadful neurological consequences for American children. There was an audience of parents who, because they weren’t of course seeing many cases of diphtheria, pertussis or tetanus, thought why should I vaccinate my child if there is a risk that this child might end up with the same type of dreadful physical and neurological problems that were shown in this exposé.

Q: Was there an anti-vax movement in Canada before then?

A: In the 1850s, Britain brings in a mandatory childhood immunization requirement and that generates huge parental opposition because there was no guarantee that the vaccine (for smallpox) was safe or necessarily effective. So from that point there’s the emergence of an antivaccination movement, which, with trans-Atlantic migration, spreads to the United States and Canada and obviously to the other British colonies like Australia and New Zealand.And certainly in the Canadian context, we had the 1885 smallpox epidemic in Montreal and that prompted both an English and a French antivaccination movement.

Q: The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom of 1982 emphasized an individual’s right to appeal to the courts if a person believed their rights were being infringed upon. How did that affect Ontario’s immunization act?

A: There was the Charter and the emergence of the Canadian Committee Against Compulsory Vaccination in 1983. The CAVC pointed to sections of the Charter guaranteeing personal liberty which led health and legal experts in the Ontario government to realize that the 1982 Immunization Act could be open to legal challenges. And so the result of this is that in the 1984 amendment a philosophical exemption is added to the act.

Q: You say there was a period around 2015 when the former Liberal government of Ontario considered removing the philosophical exemption. (At the time, there were up to 30 per cent of kids in some Toronto schools who were not up to date on vaccinations.) Can you tell me what happened?

A: My impression was that the idea was floated and it got such a negative response that they opted instead for the what amounted to mandatory education sessions for parents seeking exemptions. The legislation very clearly states that the local medical officer has the right to exclude the child from school when there is an outbreak of a disease against which he or she is not immunized. Once the disease is discovered you get sent home. You have to stay there until the disease is no longer present in the community. So, depending on the disease and it’s infectiousness, what we’re talking about is potentially months of a kid being at home. So the education sessions were a way of reminding parents of what would happen if they did not immunize their kids.

The stress on education goes back to the 1880s because the new provincial board of health was really, really focused on persuasion, not coercion. And even today you see that so clearly with the way that that regional and local health departments have tried to come up with effective ways of reaching out to populations that might be hesitant about getting the COVID vaccine. The latest variation on the public health practice is that it’s incumbent now on family doctors and other health care professionals, whenever possible, to talk up the benefits of the vaccine, but to do it in a way that allows the hesitant individual to ask the questions that he or she needs answers to before they make up their own mind.

Q: Has the philosophical exemption lead to more parents opting not to vaccinate their kids?

A: Studies have shown that only a very small percentage of parents applied for the exemption, two to three per cent. At the turn of the 21st century it was still only two to three per cent using the exemption. I think it may be marginally higher, maybe three per cent. So we have to be careful. Is this a real problem?

Q: How did the infamous study on 12 children published in the Lancet in 1998 falsely link autism to the vaccine for measles, mumps, and rubella?

A: The Lancet published the study and right beside it, a pair of peer reviewers ran an article that said 12 cases wasn’t enough and questioned the findings. But the study came out just after the crisis of mad cow disease, at a time when people in Britain had been told it was safe to eat beef and it wasn’t safe because infected beef could lead to a variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. So it was in this atmosphere that the British press championed the study. And the public health people weren’t quickly able to combat the emotions which the paper and fear of autism caused for British parents. In retrospect many in the medical community recognized that peer review had failed and failed badly. In 2005, one rather dogged reporter, a man named Brian Deer, was able to publish a series of four absolutely searing articles that exposed the study as fraudulent and that led the editor of the British Medical Journal to contact Deer and finance more of his research. Most of the study’s authors recanted, except for one who was brought before the General Medical Council in the U.K. and stripped of his license to practice medicine. In 2010, the Lancet finally retracted the article but measles outbreaks in 2008 and 2010 demonstrated the long term impact of the decline in measles vaccination.

Question: Has social media led to an increase in this anti-vax movement?

Answer:Now, it’s really hard to tell. I mean, everything I’ve been reading lately suggests that the major thing that social media has done is simply to magnify the voices.

Article From: The Star

Author: Patty WinsaData Reporter