France, Italy and Greece have mandated shots amid calls for Canada to do the same

The debate over mandatory COVID-19 vaccines for health-care workers is growing louder in Canada as more countries move forward with the controversial approach in order to safeguard health-care settings and fight the spread of more contagious variants.

Requiring vaccinations as a condition of employment in hospitals, long-term care homes and other sectors involving hands-on work with patients is not new in Canada — and experts feel it should be no different when it comes to this pandemic.

Canada lacks detailed data on the percentage of health-care workers who have been vaccinated. But more than 80 per cent of eligible Canadians have at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and close to 60 per cent have two — an amazing feat, no doubt, but one that is already showing signs of tapering off.

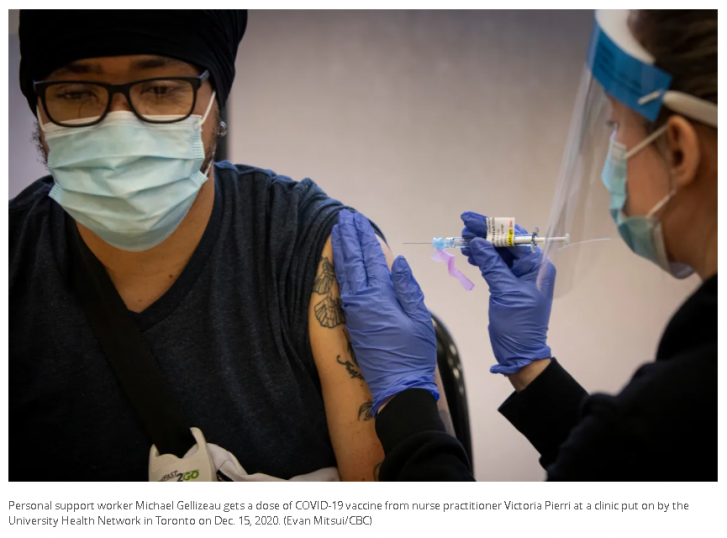

Health-care workers were among the first to get access to COVID-19 vaccines in Canada in order to protect them and their patients from infection and prevent hospitals and long-term care homes from being overwhelmed by outbreaks.

But the question of whether they should now be required to get vaccinated to do their jobs is growing more urgent as Canada’s vaccination campaign slows, ahead of the reopening of the border to U.S. travellers and the start of school in September.

“I absolutely think we should make COVID-19 vaccines mandatory in health care — I think it’s a no brainer,” said Dr. Nathan Stall, a geriatrician at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto and a member of Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization.

“It’s extremely important that we have those who are caring for our most vulnerable with direct, hands-on care be fully vaccinated. There should be no ifs, ands, or buts to that.”

Debate over mandatory vaccines in Canada

France has ordered all health-care workers to get vaccinated by Sept. 15 as the more contagious and potentially more deadly delta variant drives COVID-19 levels back up. Greece and Italy also have put similar rules in place.

The Ontario Medical Association and the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario have called for mandatory vaccines for health-care workers in Canada’s largest province, where delta is estimated to make up more than 90 per cent of latest COVID-19 cases.

But Ontario Premier Doug Ford said last week that health-care workers have a “constitutional right” to opt out of vaccination, despite the province mandating immunization policies for long-term care home staff in order to protect vulnerable residents.

“I think it’s their constitutional right to take it or not take it,” he told reporters Thursday. “No one should be forced to do anything.”

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney has also repeatedly dismissed the notion of mandatory vaccines in the province, even amending the province’s Public Health Act to remove a 100-year-old power allowing the government to force people to be vaccinated.

“These folks who are concerned about mandatory vaccines have nothing to be concerned about,” he told reporters during the Calgary Stampede last week.

Proponents of mandatory COVID-19 vaccines for health-care workers are quick to point out they’ve already been required to be vaccinated against other highly infectious diseases for decades — including some less severe than COVID-19.

“I have to be vaccinated against hepatitis B, I have to be vaccinated against measles, and I have to do a tuberculosis test periodically, otherwise I can’t work at my hospital,” said Dr. Kashif Pirzada, an emergency physician in Toronto.

“There’s no reason why a COVID-19 vaccination would be unconstitutional in that framework. We already require vaccinations against other diseases as a term of employment, so I don’t see why this is any different. And this is a much deadlier disease.”

‘COVID-19 is not influenza’

A recent viewpoint published in the medical journal JAMA argued that just as health-care workers should not “inadvertently spread contagious infections,” like measles and influenza, to their patients and colleagues, COVID-19 should be no exception.

An analysis in the Canadian Medical Association Journal earlier this year called for each provincial and territorial government to mandate vaccines for all private and public health-care workers because of their increased risk of catching and spreading COVID-19.

Flu shots aren’t mandated for Canadian health-care workers, and the authors of the CMAJ paper cite a 2019 case won by nurses in British Columbia against mandatory flu vaccines. But they say the same should not be true in the pandemic, because “COVID-19 is not influenza.”

The debate around mandating flu shots for Canadian health-care workers in the past may be driving the recent concerns in the pandemic, Stall said. But he argues that the case for compulsory COVID-19 vaccines is much stronger.

“We know that this is more transmissible, the consequences at the patient level are much more severe than influenza and the disruption to both the health-care workforce and the health-care system is much more severe with COVID-19,” he said.

“Health-care workers have a fiduciary responsibility to place the needs of their patients and those that they’re caring for first.… I don’t think that those individuals should be providing direct, hands-on care to long-term care residents and other frail and vulnerable individuals.”

Raywat Deonandan, a global health epidemiologist and associate professor at the University of Ottawa, says while it’s unethical to deny someone life-saving care if they have a deeply held belief against vaccines, it is ethical to refuse them a job.

“If you’re a health-care worker who is denying vaccination, well, you need to get a different job — and you have that option,” he said.

“But for a patient, it’s probably your right, to some extent, to be skeptical about pharmaceuticals — [and] you have a right to health care while you figure that out.

“So there’s that delicate balancing act. We have to accommodate some of this, but not all of it.”

Reasons for vaccine hesitancy

Toronto-based pharmacologist Sabina Vohra-Miller, who co-founded Unambiguous Science and the South Asian Health Network, says that not all health-care workers should be put in the same category.

“If you’re talking about physicians that’s one thing. But if you’re actually looking at the fuller spectrum of health-care workers it’s a different situation,” she said. “You don’t necessarily have people coming from as much either privilege or accessibility.”

Vohra-Miller says health-care workers can include personal support workers, long-term care workers and community outreach staff that could have different barriers to getting vaccinated, including education, paid sick leave or childcare.

“They’re working multiple jobs at any given time. They’re working crazy hours, just to make ends meet,” she said.

“When people think of health-care workers, they just automatically think doctors and nurses and people who have access and have all this education on vaccines and should be able to make these decisions — but that’s not necessarily the case.”

Impact on the health-care system in a 4th wave

Pirzada says if a significant proportion of health-care workers remain unvaccinated in the fall, when COVID-19 levels are expected to rise again, there could be significant impacts on the Canadian health-care system.

“When the rates of the virus increase in the community, it’s going to start hitting health-care workers,” he said. “If let’s say 30 per cent of our workers are not vaccinated, you’re going to knock out a large portion of the workforce, right at the time when we need them, when community transmission is going to be at its highest.”

Stall says ensuring as many health-care workers are vaccinated as possible will maintain stability in the health-care system and mitigate future outbreaks in settings linked to under-vaccinated staff, like long-term care homes, as recently seen in Burlington and Hamilton.

“We know the havoc that an individual outbreak can cause in terms of the health-care system,” he said.

“We need leadership on this issue. We need to do it now while case counts are low — before the fall, before it’s too late, when we may have outbreaks in our health-care settings.”

Article From: CBC

Author: Adam Miller