It was hailed in the early, chaotic days of the pandemic as a true breakthrough in the fight against COVID-19: a portable, Ontario-made testing platform, half the size of a lunch box, that could detect the deadly virus that causes COVID in less than an hour.

But 16 months into the pandemic in Ontario, that miracle cube has turned out to be something else entirely: a sinkhole for public money and a cautionary tale about lobbying, political influence and the perils of moving too quickly, even when quick action is required.

Thanks to a breakneck process where procedures were hurried and safeguards left out, Ontario spent $10 million it will probably never get back on unproven COVID tests it will almost certainly never receive. The testing contract the province signed left money tied up through the summer and into the fall even as other parts of the lab system went begging, helping exacerbate a deadly second wave.

But the deal was something else, too. It was an early plot point in a pattern that has quietly helped shape Ontario’s COVID response: a decision, made at the urging of conservative lobbyists, to favour one private interest over others at a crucial hinge point in the pandemic.

“It’s a who you know and who you hire system of government policy-making instead of government making decisions based on the merits,” said Duff Conacher, the co-founder of Democracy Watch and a frequent critic of the lobbying industry. “It shows that the Ford government decision-making process is open to hearing from Ontarians, as long as they hire one of these lobbyists.”

But in late March 2020, all of that was in the future. With Ontario totally shut down and COVID tests running dangerously short, the province was looking for answers. And an Ottawa company called Spartan Bioscience, its voice amplified by a team of top Tory lobbyists, was ready to offer them.

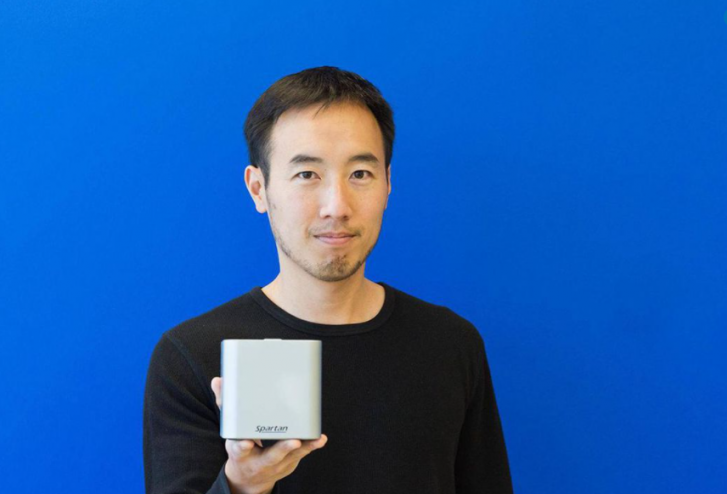

From the outside, the Spartan system looked like a video-game console or a streaming box for your TV. But Spartan hailed it as a game-changer — a miracle in a cube that could replace entire molecular labs and bring rapid COVID tests, quickly, to small towns, Indigenous communities and hard-hit spots like homeless shelters and long-term-care homes.

Spartan, founded by two Ontario doctors, had initially marketed its cube to test water for the bacteria that causes Legionnaires’ disease. But when COVID hit, Spartan pivoted. And in a matter of months, the company was pitching its new COVID test to governments across Canada.

The sales job was aided in Ontario by a team of lobbyists with deep ties to the conservative movement, and to Doug Ford’s government in particular, including Trisha Rinneard, Education Minister Stephen Lecce’s former director of issues management. It started before the company had Health Canada approval for its test, and before the system had been fanned out to independent labs for verification of Spartan’s own, internal results.

But in the early days of the pandemic, none of that seemed to matter.

On March 25, the same week three lobbyists from Wellington Advocacy, a uniformly conservative firm, including Rinneard and Nick Koolsbergen, a top federal and provincial strategist, registered to lobby on behalf of Spartan, the Ontario Ministry of Health directed Public Health Ontario to buy a one-year supply of the company’s COVID system.

That same day, according to the Ontario auditor general, Public Health Ontario signed an $80-million, sole-sourced deal with Spartan, pending Health Canada approval, and agreed to pay the company an immediate $10-million deposit.

Public Health Ontario signed the Spartan deal, at the explicit direction of the province, a full a month before its own board had a chance to review the contract and with such haste that its own team failed to specify a time frame for the platform’s approval by Health Canada, an omission that could cost Ontario millions.

But that wasn’t the biggest problem with the deal. “I think … they thought that a rapid test that could be deployed anywhere would revolutionize things,” said Dr. Kevin Katz, the medical director of Toronto’s Shared Hospital Lab. “If you actually spoke to lab physicians, I think a lot of us would have said, ‘Yeah, right.’ ”

The troubles with the Spartan system emerged almost as soon as the first cubes landed in Ontario’s hospital and public health labs. Health Canada can issue a provisional approval for a testing platform based on a company’s own results. But any major lab system will do its own validation — testing the system against the established standard — before it deploys a new test.

The validation results for Spartan were, from the beginning, a letdown.

“I think the one word that I hate most about the pandemic is everybody using the word ‘game-changing’ in anticipation of something that is never game-changing,” said Dr. Larissa Matukas, the head of microbiology at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. “And that’s essentially what happened.”

The Spartan system — a hand-held PCR-based DNA analyzer, individual test kits and software to analyze the results — was only catching about half of positive cases, according to Katz, who helped validate the platform. And with “50 per cent sensitivity, you may as well be flipping a coin,” said Rob Kozak, a clinical microbiologist at Sunnybrook Hospital. In other words, the test didn’t work anywhere near well enough to be useful. “It was designed for speed,” said Katz. “And we knew that it would be sacrificing a little bit on (sensitivity), but it just seemed to sacrifice a little bit too much.”

In May 2020, Health Canada amended its approval for the Spartan cube, barring its use in clinical settings. But Ontario, which had already paid the company $10 million, didn’t get its money back. Spartan kept Wellington on retainer, eventually adding Sam Duncan, who was until April 2020 the top policy official in Doug Ford’s office, as it tried to revamp the platform. In January, Health Canada issued another approval for the Spartan system, but soon, new problems emerged. Even after months of additional time in the lab, the Spartan cube was still turning up far too many inconclusive tests. And in January, the company pulled the system again.

By that point, though, time was running out. Spartan had been bleeding cash for months. It had poured all its funding from advance orders, plus government grants, into ramping up manufacturing and production. In November, the company took out a $7-million loan, at 12 per cent annual interest, twice the rate of earlier financing, to keep operations running. But four months later, almost a year into the pandemic, it still couldn’t sell any tests, let alone deliver the ones customers, like the Ontario government, had already paid for.

On April 5, 2021, just over 12 months after signing the massive Ontario deal, Spartan Bioscience filed for creditor protection. The company furloughed 60 of its 80 employees and 11 co-op students to keep what cash flow it had from draining away.

In documents submitted that day, the Government of Canada, which had provided Spartan with millions in development and production funding, was listed as the company’s largest creditor. Number two was Public Health Ontario. Spartan still owed the government agency $9.8 million of its initial $10-million deposit. “A few of us raised our eyebrows at the amount of money that was floated before it was actually proven to be working,” Katz said. “The money for the conventional PCR testing at that point in time wasn’t nearly as fulsome as that.”

Jeffrey Fenton, a spokesman for Spartan, declined to answer questions about the testing platform, the Public Health Ontario contract or Wellington’s lobbying work for this story. “At this time, we remain focused on our product and our vision to help contribute to a stronger future for Canada’s bioscience sector,” he wrote in an email.

There were dozens of other creditors on the list Spartan submitted that day, all but four of them unsecured, including Wellington Advocacy. When Spartan declared insolvency, the bioscience company still owed the lobbying firm almost $68,000.

***

As part of a series on lobbying during COVID, the Star created a database of every active lobbying registration in Ontario in March 2021, about one year into the pandemic. The results revealed a clear pattern: a large majority of the lobbyists with the most clients had open, and in many cases active, ties to the premier or the PC party.

“It’s just (a) fact that this government very much listens to its friends, many of whom are now lobbyists,” said one conservative lobbyist. “And that was just very different under someone like (Stephen) Harper, who was there to, you know, govern.”

Partisan lobbying isn’t new in Ontario. Nor is it restricted to conservatives. But some government and industry insiders do believe that it has become significantly more pronounced under Ford.

“It really, really does matter that you know the (right) people,” said a second lobbyist. “You need to have those connections … to navigate through Queen’s Park currently, otherwise, it’s impossible to get through.”

The Ontario registry doesn’t say exactly when Wellington started lobbying for Spartan. The Ontario rules only state that lobbyists need to register within 10 days of their first contact with a public official. But according to contract information filed in Alberta, the firm was working for Spartan at the latest by March 22, 2020.

That was three days before the Ontario Ministry of Health directed Public Health Ontario to sign a sole-source contract with Spartan “as soon as possible.” According to the Ontario auditor general, the very next day, March 26, the government paid the company $10 million. It wasn’t until November 2020, after the AG’s office had reviewed the deal, that Public Health even asked for its money back. More than 90 per cent of it has yet to be returned.

“It is a questionable practice to buy into something without understanding the evaluation process that needs to happen in order to deem (it) acceptable,” said Matukas. “Anything that’s Health Canada approved still then needs to be validated and evaluated by any clinical laboratory that’s going to use it for diagnostic testing. … And most things that have come through our labs don’t actually meet those acceptance criteria. And Spartan happened to be one of those things.”

Spartan Bioscience is still in creditor protection, seeking new investment or ownership.In late June, the company sought court approval for a sale to its top-ranked creditor, Casa-Dea Finance Limited, a six-month-old lender that shares office space and ownership with a cable and wire company in Trenton, Ont.

Spartan’s founder and former CEO, Dr. Paul Lem, left the firm in November 2020. He recently self-published a self-help book online. (Lem did not respond to a request for comment sent through LinkedIn.)

Three Wellington lobbyists, Rinneard, Koolsbergen and Duncan, are still working for Spartan, according to information filed with the province. A fourth Spartan lobbyist, Rachel Curran, left Wellington last year to join Facebook Canada.

Kayla Iafelice, a Wellington vice-president, declined to answer any questions on behalf of the firm for this story. “Thank you for your request, but as company policy we do not comment on client matters,” she wrote in an email. “Wellington Advocacy strictly adheres to all lobbying requirements.”

Public Health Ontario also declined to answer any questions about the deal, citing the ongoing court process, as did a spokesperson for Ontario’s health minister. A spokesperson for the Ontario Ministry of Health sent a response, but did not answer any of the main questions in detail. “The Spartan COVID-19 laboratory test kit was intended to support testing capacity in remote and vulnerable populations; decrease turnaround times; and reduce the pressure on health-care workers in the health system,” David Jensen wrote in part.

Still, Ontario wasn’t the only province left fighting for scraps when Spartan filed for insolvency. Spartan still owes a public research lab in Quebec almost $9 million, a Saskatchewan health region about $220,000 and $20,000 to Northwest Territories Health and Social Services.

Nor, for that matter, is it the only province run by a conservative government that Wellington lobbied, successfully, on behalf of Spartan. Four Wellington lobbyists were registered at different times for Spartan in Manitoba. According to insolvency documents, the company still owes an agency of the Manitoba government $1.65 million.

In Alberta, meanwhile, where Wellington runs an office stacked with veterans of Jason Kenney’s United Conservative Party, Koolsbergen, who ran Kenney’s 2019 campaign, signed a contract to lobby for Spartan in March 2020. Eight days later, the Alberta government announced a deal to buy 100,000 Spartan test kits. As of April 2021, Spartan still owed Alberta more than $1.7 million.

Article From: The Star

Author: By Richard WarnicaBusiness Feature Writer