The plain truth is we’re running out of arms that haven’t already had needles jabbed into them, and Round 2 is full swing

Even as Canada sets records for its vaccination effort, which now averages 420,000 shots a day, the rate of first doses is dropping. So while 120,000 first doses were administered on Sunday, that’s well short of the more than 300,000 a day given out a month ago. And that fall is being seen across the country.

When New Brunswick unveiled its reopening plan in late May, Health Minister Dorothy Shephard forecast that Phase 1 would begin on June 7. That step depended on achieving one big goal: getting first doses of COVID-19 vaccine into at least 75 per cent of eligible residents. “I looked at it, and said, “Maybe,” recalls Kevin Wilson, a Halifax-based epidemiologist who publishes extensive threads on Twitter featuring vaccine and pandemic graphics. “The closer they got to that deadline, it went from plausible to ‘technically within the laws of physics’ that it could happen,” he says. New Brunswick missed the deadline, and is expected to hit that 75 per cent metric on Monday, a week behind schedule.

Right now, most of Atlantic Canada is focused on getting first doses into arms, Wilson explains. “We want to run up the score on first doses as much as possible, then switch to second doses,” he says. The strategy, which takes advantage of the region’s low COVID-19 case count, means that its provinces are starting to pass other provinces in terms of first doses. Yet, even on the East Coast, it’s taking longer to hit that next first-dose benchmark.

The nation’s first-dose slowdown is not only expected, but also a good signal. To put it bluntly: Canada’s first-dose strategy is such a success—we are No. 1 among all OECD nations in terms of first doses—that we’re running out of arms in which to jab needles full of vaccine.

“We’re getting to the point where first doses are no longer a success metric because you can’t move the needle anymore,” Wilson says. After using first doses as the main metric in his daily vaccine graphics for the past four months, he’s going to change to second doses in the next few weeks for a simple reason: “No one will be meaningfully trying to max out their first doses because we’ll have functionally maxxed them out.”

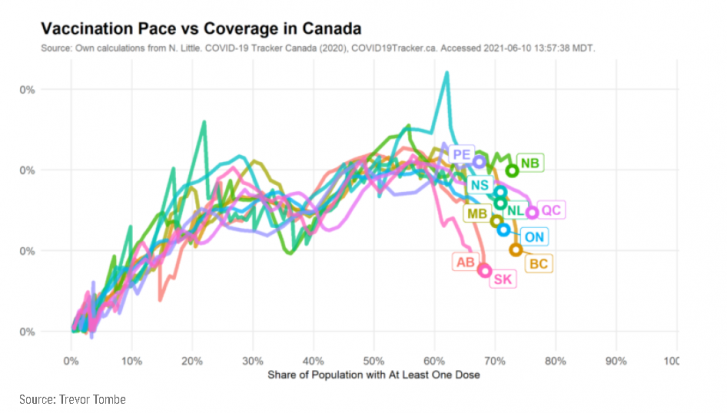

Overall, 73.6 per cent of eligible Canadians have gotten at least one dose, according to data crunched by Trevor Tombe, an economist at the University of Calgary who has become the go-to source for vaccine data in Canada. When he built his modelling graphics for each province, he put in a ceiling of 85 per cent of eligible populations getting first doses based on polling data, and, as of now, his forecasts show most provinces going above 80 per cent this summer, with Quebec likely to hit 85 per cent.

When looking at eligible residents who haven’t yet gotten vaccinated, the range goes from a low of 19.5 per cent of Quebec’s eligible population to a high of 28.7 per cent of eligible people in Prince Edward Island (the territorial share ranges from 15.5 per cent in Yukon to 28.7 per cent in Nunavut).

New polling from EKOS Research reports that 89 per cent of Canadians either have gotten or will get vaccinated, though an Angus Reid poll from mid-May puts that number at 82 per cent. Both polls suggest that around 10 per cent of Canadians don’t want to be vaccinated, period. Subtract that figure from those who still haven’t gotten doses, and the shrunken size of the remaining pool becomes evident, ranging from less than 10 per cent in Quebec to perhaps more than 15 per cent in Prince Edward Island.

That last cohort of first-dose candidates includes “many who are intensely not interested,” Wilson notes, with some still undecided about whether to get immunized, and others who aren’t seeking appointments. “That last 10 per cent or so will be more challenging than the first 75 per cent in most provinces,” he says. He wants governments to do “whatever dumb gimmick you can come up with to say, ‘Hey lot of people here, want a COVID vaccine?’ ” As other nations have shown, nothing should be off the table, including taking vans loaded with vaccine to workplaces; lotteries for those already immunized; free tickets to sports events or even “shots for shots” nights at bars. “Put the elbow grease into it and get those people vaccinated,” he says.

Some of those inducements are already being rolled out as provinces struggle to meet first-dose benchmarks. While many provinces are experiencing a slower pace of first-dose vaccinations, Tombe notes that the trend is particularly noticeable in Alberta and Saskatchewan, whose declines in uptake began before they reached the higher first-dose shares of other provinces.

Alberta needs 70 per cent of eligible residents to get first doses before it moves into Stage 3. With the province giving out fewer first doses per capita than any other province except Saskatchewan, and lots of clinics unable to fill vaccine appointment slots, the government decided not to take a chance that it would miss that goal: over the weekend, Premier Jason Kenney announced a lottery—three winners each of $1 million—for everyone who has first shots. “We need to just nudge those who haven’t gotten around to getting their vaccines yet,” said the premier. “Please do your part, because now a vaccine shot is also your shot at $1 million.”

Even as the number of first doses decrease, second doses are surging. Last week, the federal government announced that seven million Moderna doses would be arriving this month, part of the 20 million expected in June alone. The new Moderna shipment “will not likely have an effect on the timing of the first dose milestones I’m projecting,” Tombe says, “but will absolutely move forward the fully vaccinated milestones. It looks like we may very well achieve 75 per cent of eligible individuals with their second shot in July. That’s incredibly good news.”

Article From: Maclean’s

Author: Patricia Treble