With the scan of a code you may eventually be able to board a plane, or get into a bar. But vaccine passports are also an ethically fraught, logistical nightmare.

So here’s the thing: I would like to see Blink-182 in concert. I would like to stand on trampled, yellowing grass at LeBreton Flats in Ottawa with a plastic beer cup in my hand, and yell the words to All the Small Things, and feel the river breeze on my face. I would like to do these things in the summer of 2021.

A July music festival may sound like a pipe dream—or a nightmare—at the beginning of spring this year, when only about 12 per cent of Canadians have received a single dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and case numbers are skyrocketing in many parts of the country. A few months down the road, if it turns out that public health authorities deem a mid-July display of “Crappy Punk Rock” (in the band’s own words) too risky, I won’t be surprised. I’ll sing those lyrics from my balcony: “Say it ain’t so, I will not go.”

But my fantasy may not be so far-fetched. Mark Monahan, the executive director of Ottawa Bluesfest, says he’s “hopeful” there will be a festival this year. Headliners are already booked. Aside from Blink-182, there’s Jack Johnson, Blue Rodeo and Alanis Morissette. Of course, none of them can predict right now whether the show will go on. Isn’t it ironic? (Did I misunderstand the meaning of that word?)

“We’re exploring potential tools in order to allay any fears about events going forward,” Monahan says, including requiring negative COVID-19 tests and providing on-the-spot rapid testing. With all the promise of an expected ramp-up in vaccine availability, the festival has started thinking, too, about whether it could ask festival-goers for proof of vaccination.

“All we want to do is try and mitigate risk, and provide the best possible situation for people who want to go back and attend concerts again,” Monahan says. He knows that “vaccine passports” are a controversial idea. But despite little guidance from the Canadian government on whether or not their use will be sanctioned, the idea is gaining traction in the private sector. “It’s not just us, right? It’s sports teams, it’s meetings and conventions. We’re not the only industry facing the same problem,” he says. “We’re just looking for a way to get back in business.”

We are still learning about the disease that has disrupted our lives for more than a year. We are still learning about its variants and about what vaccines can and can’t do. There’s an awful lot we still don’t know. But we are nonetheless inching toward an awkward new phase of the pandemic: one where some countries have vaccines and others don’t, where some people are vaccinated and others are not, and where demands to reopen will only get louder and more urgent.

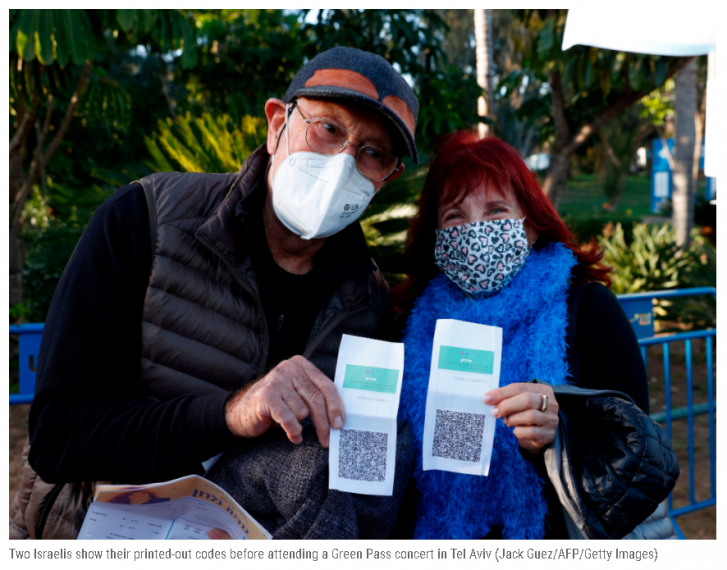

Vaccine passports are already being used in other parts of the world. In Israel, a “Green Pass” that confirms vaccination status has become an essential passe-partout for daily life, allowing access to gyms, movie theatres, restaurants and other public spaces. Europe, which has fallen behind Canada in the race to vaccinate its population, is a testing ground for myriad new technologies that could be applied in much the same way.

Whether we like it or not, experts say, Canada will be pressured into coming up with a system to verify that Canadian travellers have gotten their shots. After decades of government failures in nationalizing and digitizing health data, the development of that system is all but guaranteed to be a logistical nightmare. Its potential applications in a broader post-pandemic world are ethically fraught. And we are already falling behind.

***

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has confirmed Canada is among the countries considering a vaccination requirement for international travellers, as of early April. His health minister, Patty Hajdu, has called it a “very live” issue among G7 nations, and said there will need to be “some consistency and some collaboration” among the countries.

But Canada has stalled on setting out its plans while other countries are already road-testing technological solutions to opening up travel in a partly vaccinated world. And at home, the provinces and territories, which govern the health data that could be used for this purpose, are working in silos.

“There’s no engagement at this moment led by the government in terms of trying to find the best way to approach this issue,” says Paul-Émile Cloutier, president and CEO of HealthCareCAN, a national association for health organizations and hospitals. “This is really no longer theoretical,” he says. “We have to start thinking through the design and the application of whatever tool, if it’s a passport, if it’s testing that we have at the airport. That has to be done now.”

The international community is falling over itself to figure this out. The World Economic Forum is developing a “CommonPass” for travellers to show their COVID-19 status. In apparent competition with that system, the International Air Transport Association, which represents 290 airlines, is developing an “IATA Travel Pass.” Its members include Air Canada and WestJet.

Countries are setting up their own systems in anticipation of their utility. The model is Israel’s Green Pass, launched in February, which links to national health ministry data and gives users a scannable code—displayed on a phone or printed on a piece of paper—that confirms their COVID-19 status. It launched with the ability to confirm whether someone was vaccinated or whether they had already recovered from an infection. In March, more features were added that allowed a non-vaccinated person to link the app to a recent negative test result.

An Estonian pass is being piloted in Estonia, Hungary and Iceland, with support from the World Health Organization (WHO). Others are being developed by Germany, Denmark and Sweden. A European Union “Digital Green Certificate” proposal was announced in early March and is currently being developed; Saudi Arabia announced its own system in January.

What the United States decides to do will necessarily weigh heavily on Canada’s decision. New York state has announced an “Excelsior Pass” that would confirm vaccination or a recent negative test. The Washington Post confirmed in late March the U.S. government is already working with agencies and private developers to create a national vaccine passport program that uses scannable codes.

Although the WHO is working on international standards for “digital vaccination certificates,” which Canada will very likely fall in line with, in March it urged countries not to use these for international travel. At least, not now. There are two major reasons for that. The first is there’s still a limited global supply of vaccines. “We don’t have enough vaccine being distributed, so whatever freedoms you think you’re going to grant a small section of society, you’re now constraining the freedoms of a large section of society,” says Françoise Baylis, a professor at Dalhousie University and Canada Research Chair in Bioethics and Philosophy.

The ideal path forward would be to focus on accelerating vaccine distribution to all parts of the world, Baylis says, so that you are looking after both the interests of travellers and the interests of the places they’re travelling to. Canada could even consider donating some of its vaccine surplus to countries that suffered disproportionate economic impact due to a lack of Canadian tourists, she suggests. Even if we do that, most estimates suggest it will take several years to vaccinate the whole world. Herd immunity is a long way off.

The second reason the WHO says we should be cautious is that scientists have not concluded vaccines prevent transmission of the virus. A vaccinated traveller could conceivably still bring it onto a plane and across the border. And we still don’t know how long immunity from a vaccine may last.

“From a science point of view, I think society and government have to realize that it is a calculated risk,” says Dr. David Hill, scientific director of Lawson Health Research Institute, and a vice-president of both research at London, Ont.’s major hospitals and of HealthCareCAN’s health research committee. But he says a level of risk is acceptable, and waiting for scientific certainty on transmission before moving ahead with an “inevitable” system could be even riskier. “The global economy cannot go on in shutdown. We have to have global movement reinstated,” Hill says. “Canada cannot be the only country that’s stuck in a silo come the end of the summer.”

Early in the pandemic, the WHO told countries they should not shut their borders to stem the spread of COVID-19. Countries did it anyway. And they were right to. Restricting travel is a highly effective way to put a pin in transmission of the virus, as Canada’s Atlantic provinces continue to prove with their tightly controlled borders and low case counts.

If the global rush to come up with a digital immunity pass wasn’t enough proof that the world will flout the WHO’s recommendations again, one country is already requiring proof of vaccination for entry: China has reportedly resumed processing visas for foreigners from dozens of countries, but only those who can prove they’ve specifically received a Chinese-made vaccine.

The Canadian government as of the end of March had little to say about its intentions. Foreign governments and international agencies are “exploring the use of immunization certificates as a tool to support the reopening of societies and economies,” Global Affairs Canada acknowledged in a carefully worded statement. “As some jurisdictions begin to consider granting privileges to vaccinated individuals, any such consideration in the Canadian context would be based on sound scientific evidence.”

Chief Science Advisor Dr. Mona Nemer is expected to deliver a report on vaccine passports sometime in April. Her advice may pave the way for a federal plan. But provinces are staking out their positions already.

British Columbia Premier John Horgan told reporters that the issue was raised at a late February first ministers’ meeting, with most premiers agreeing that a vaccine requirement for international travel will be “absolutely imperative,” in Horgan’s words. (A recent poll of 800 British Columbians, from Research Co., found Horgan’s constituents are 73 per cent in favour of that idea.) Manitoba is already issuing vaccine certificate cards. Ontario has promised residents will receive similar documentation, with Health Minister Christine Elliott suggesting last fall that it could be used in workplaces and movie theatres, and Quebec is looking at using its existing database of vaccine records for the same purpose.

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney, on the other hand, has promised the opposite. Vaccine passports or any documentation, he said at a town hall in February, “would be a violation of the Privacy Act.”

***

So far, the national conversation around vaccine passports has been a black-and-white debate about whether they’re good or bad. There has been much less discussion about what it would take to do it. “Quite honestly, a practical application of them in Canada puts them kind of on the outside limit of what’s achievable,” says Ian Culbert, executive director of the Canadian Public Health Association. “They look like a great and simple solution, but as with most things, the devil’s in the details.”

For decades, Canadian governments across the board have failed to modernize health systems and create national standards for health data. Even within provinces, health regions aren’t always aligned. And Culbert says most provinces had no system to digitally record adult immunizations even before COVID-19.

There will need to be national standards for what is considered “authentic proof” of a person’s vaccination record, says the Ottawa Hospital’s Dr. Kumanan Wilson, CEO of CANImmunize and an innovation advisor for Bruyère hospital. Canada will need to be aligned with the U.S., he says. And within Canada, provinces will need to be aligned. “You don’t want to have a situation where your record in Ontario is not accepted when you cross the border into Quebec and vice-versa.”

Early in the pandemic, about a year ago, there was some buzz in scientific, academic and government circles about the concept of an “immunity passport,” but it was quickly shot down due to myriad scientific and ethical concerns. Some of those are still at play. But the shutdown of that early conversation may have prevented us working through some of the technological and scientific challenges we’re facing now, Wilson says.

Wilson has written that an idealized system could look something like Israel’s or Estonia’s. Marcus Kolga of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute recently argued in Maclean’s that Canada should just go ahead and buy the Estonian tech. It uses blockchain technology and a quick response (QR) code tied to a person’s identity, which can be downloaded on a mobile phone app or printed out on a sheet of paper (or the cover of a magazine). When scanned, the code links back to an official dataset that confirms your vaccination status. To safeguard against new scientific data—say, if it turns out that vaccines are effective for a shorter time than we hope—you could build in a six-month expiry, as Israel has.

On the whole, using such technology makes for a system that is easier to authenticate and more impervious to fraud than, say, a paper receipt. It would be a major step up from the system used in the most important international precedent for a COVID-19 vaccine passport. For many years, travellers wishing to enter certain countries in Africa and South America have had to present proof of a yellow fever vaccination in the form of a yellow paper card, filled out by hand.

Canadians are already getting used to using QR codes in some pandemic-era settings. Many restaurants have ditched physical menus in favour of QR-code stickers on dining tables that link to online ones. Parents of students in the Toronto District School Board can use a smartphone app to answer COVID-19 screening questions, allowing their kids to flash a QR code at the school doors in lieu of providing a signed paper health pass.

No other health or personal information would necessarily be linked to this sort of system, significantly mitigating privacy concerns, says Frank Rudzicz, a health researcher and associate professor of computer science at the University of Toronto. Though privacy and cybersecurity fears are front of mind for many skeptics, he says making such a system cybersecure is doable, and the “slippery slope” argument—that a COVID-19 vaccine app could eventually be used to download and track all kinds of other information—is a “false start.”

But the question is: where would the app pull your health information from? That’s where things get complicated, and a unified national approach starts to feel “mythical,” as Rudzicz puts it. Israel’s Green Pass works so well because it pulls from a single, national health dataset. Of course, that can create its own problems: non-citizens, including international students, are unable to access the pass even if they have been vaccinated.

“We’ve got to be very careful if that’s the model we’re going to use for Canada, because the realities are totally different,” says Cloutier, the president of HealthCareCAN. “Israel is not a confederation that has various levels of jurisdiction. It is very complicated here in Canada.” You only have to go back over the last few months, Cloutier says, to see evidence of that. It has been difficult to get messaging consistent across provinces and in Ottawa, let alone policy.

The Canadian Medical Association Journal published a detailed “blueprint” last year for a national vaccine registry, but despite murky federal attempts to procure such technology, according to reporting by the Globe and Mail, no system is currently in place.

It’s still possible to proceed with a hodgepodge approach, where each jurisdiction sets up its own way to link up to a barcode-based system, Rudzicz says. Even so, Canadian governments aren’t exactly world leaders in rolling out new technology. And doctors and health regions across the country are already notoriously slow on the uptake of other e-health technologies, putting Canada well below average in a 2019 Commonwealth Fund survey of developed countries. “I have major doubts that we would be able to pull it off,” Rudzicz says. “In practice I could see it being a catastrophe.”

You’d think that this moment would create the impetus for governments to finally work through the kinks of a national system. You’d think that when the pandemic began, governments could’ve jump-started such a process, and made the rollout of vaccine certificates that much easier. But it can’t really be done in the short term, Rudzicz says. “I hope I’m not optimistic to say it would take maybe five years.”

***

Whether for use internationally, at provincial borders or—and I can’t emphasize this enough—at a Blink-182 concert, there are fears vaccine passports could entrench inequalities and even backfire on their public health goals.

If vaccine certificates are available, employers may decide to make use of them. The doctors I spoke to think that COVID-19-related vaccine or test requirements are entirely appropriate in health-care settings. Places like hospitals already require things like negative tuberculosis tests, for example.

In other places where there is an obvious public health risk—like in industrial settings and congregate living situations where social distancing is not possible—employers could likely make a strong argument that employees must show negative tests or proof of vaccines, though this could prove tricky in unionized settings, says labour lawyer Neena Gupta, a partner at Gowling WLG in Waterloo, Ont. The legal argument for requiring proof-of-vaccination would be weaker in workplaces where distancing and masking measures can still be maintained, Gupta says. But many employers are lawyering up. “If employers are thinking about doing that, I joke and say your lawyer should be your next best friend.”

In federally and provincially regulated workplaces, it would be important to have a systematic approach, says Baylis, the Dalhousie professor. If there is a conversation about requiring staff to be vaccinated at long-term care homes, for example, there ought to be a similar approach for prisons.

If we get to a point where places of business ask customers to verify their status, that’s where things could get really messy, she says.

There could be discrimination against younger people who may not have access to a vaccine yet; people who can’t or won’t get one, sometimes for religious reasons protected by Canadian human rights law; people who do not have access to certain technology, like smartphones and printers; and those who are members of already marginalized groups. Baylis worries that requiring proof-of-vaccination upon entry to venues, and requiring frontline staff to determine certificates’ authenticity, could create new avenues for racial discrimination.

For people who are vaccine-hesitant or anti-vaccine, some suggest that a vaccine passport would provide some incentive to encourage uptake. But Baylis thinks it would erode such people’s trust in their institutions even further. “If you can’t have access to free movement, in effect, without this, then you’re actually not, I think, contributing to an environment in which trustworthiness will flourish.” A group called Vaccine Choice Canada, an anti-vaccination, anti-mask group that claims to promote “informed decisions,” has hinted it would gladly go to court over the issue.

Complaints could and probably will be brought to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, Gupta says. But while there’s no case law on this issue yet, if the use of vaccine passports is in line with public health measures and accommodations are offered for people who can’t or won’t get vaccinated, she says there could be reasonable arguments supporting their use. “I think at the end of the day it’s going to be a matter of personal choice. Would I personally be happy showing a vaccine passport to get in to visit the opera in Toronto, or whatever? Absolutely I would, if the alternative was I couldn’t go,” says Hill, from the London hospitals. “Are there going to be groups of people that say it’s a gross abuse of personal liberties? Yes, I’m sure there are. But it’s going to be a calculation of risk. If the only way you can fill a theatre and have live productions actually make money is to have a vaccine passport to get into the building, then that’s what people are going to do.”

The image of a theatre full of vaccinated patrons—at an opera, no less—calls to mind, at least for now, a specific gray-haired subset of the population. If a vaccine passport is used by the private sector before all adults are eligible to be vaccinated, young people may find themselves staying home while their parents and grandparents go out on the town. And venues that want to welcome boomers but require their disproportionately Gen Z service staff to be vaccinated may find themselves short of employees.

“It may be tempting for businesses to think of happy baby boomers flocking to beaches, football matches and cafés,” reads a February Bloomberg op-ed by Ferdinando Giugliano, “but inter-generational fairness looms large in this debate.” That’s a multi-layered concern. Beyond their longer wait to access vaccines—and, perhaps, the opera—young people have faced poorer economic outcomes during the pandemic despite being the least susceptible to severe COVID-19. And younger generations will bear the burden of paying down the debt this crisis has created.

Still, in the immediate term, that inter-generational struggle may pale in comparison to the political cultural wars that are already raging. In the U.S., the debate over vaccine passports, much like those over mask mandates and other lockdown measures, quickly took on a partisan tone after reports emerged about Joe Biden’s plan. “Authoritarian leftists want a Chinese-styled social credit system here in America. Vaccine passports via the Govt or private sector would create a two-tiered caste system,” Donald Trump Jr. tweeted on March 29. “Every elected GOP officeholder worth a damn should publicly oppose this un-American concept immediately!!!”

Offering alternatives could go a long way toward mitigating ethical, legal and even political concerns, experts told me. These could accommodate groups that won’t get a vaccine, or that can’t yet—such as people whose cohorts have not been offered the opportunity, or children and teenagers under 16 for whom vaccines are not yet approved. In jurisdictions like Ontario that already require children to be vaccinated against certain ailments before joining school systems, significant accommodations are already in place.

Instead of requiring proof-of-vaccination only, a country, airline or venue could ask for proof of a negative antigen or PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test, offer on-the-spot rapid testing or accept documentation showing a person has already recovered from COVID-19. If that information is digitized, a vaccine passport app could even be used to display the negative tests, as is the case in Israel.

That works for Hill. “At the end of the day, all I really want to know is that somebody is not shedding virus.”

***

Imagine for a moment that the experts I spoke with are largely wrong about what’s going to happen next. Imagine a world where the international community follows WHO guidelines, countries do not require visitors to prove their vaccination status, and the federal government washes its hands of the idea of a federal system.

That’s still a world in which COVID-19 remains a threat for the foreseeable future. It’s still a world where provinces can decide to create their own passports for local use, perhaps to the exclusion of residents from neighbouring jurisdictions. And it’s still a world where the private sector will see some utility in creating rules that make customers feel safer. “I think we may have the bottom-up approach where industry starts to create solutions, and provinces start to adopt those, and that pushes up to a federal level,” says Wilson, from the Ottawa Hospital.

As vaccination increases and if case numbers decline as a result, there will clearly be demands from businesses and vaccinated people to get things back to normal. A statement provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada implies there is a threshold in vaccination rates at which our pandemic response will shift gears: “Until a larger number of people across Canada are vaccinated, public health measures remain the foundation of the pandemic response.”

More than half of Israel’s population is now fully vaccinated, the highest rate in the world. New cases are still being reported in Israel daily, but they are on a steady decline, as is the death rate, and new variants have not proven resistant to vaccines. Despite those cheerful metrics, public health officials have advised caution, especially since the country’s children are not vaccinated.

Under eased lockdown restrictions, for the first time in more than a year families celebrated a major holiday at the end of March with few restrictions. The Times of Israel reported that 130,000 Israelis visited parks and nature reserves for the Passover holiday, with groups of 50 people allowed to gather outdoors. Up to 20 people could gather inside, and Green Pass holders could dine in restaurants. The story ran with a photo of a family of 15 gathered around a dining room table, feasting without their masks on March 27, 2021. It looks like a miracle.

The U.K. is far from out of the woods, but is approaching a similar benchmark. Half of its residents have had at least one shot, and the government is actively reviewing whether vaccine certificates can be used to allow entry into places like pubs and stadiums. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said such a thing won’t be offered until all adults have had a chance to be vaccinated; Trudeau will likely face calls to say the same.

In the U.S., where the vaccination campaign is proceeding at a dazzling pace and a Krispy Kreme promotion promises free donuts for those who’ve gotten shots, the Centers for Disease Control is still recommending that vaccinated people socially distance, wear masks and avoid medium- and large-sized gatherings in public, though they can gather without such restrictions in private.

But with legally binding rules varying state by state, private venues have started to go their own way. As of April 1, even before New York’s Excelsior Pass becomes available, and just before the youngest subset of New Yorkers will become eligible to receive vaccines, visitors to Madison Square Garden must show proof of vaccination, proof of a negative antigen test or proof of a negative PCR test to watch a hockey game. The New York Rangers experiment is the sort of thing that Mark Monahan, at Ottawa Bluesfest, is paying close attention to.

Monahan chairs an Ontario Festival Industry Task Force, which in partnership with Shoppers Drug Mart almost pulled off an honest-to-god outdoor gig on March 31. The “Long Road Back” concert had to be postponed due to heightened restrictions, but if and when it does go ahead, it may offer an early Canadian blueprint for public events in the months to come. Just 100 people were able to buy tickets to see the Ottawa band the Commotions. There was to be physically distant bistro-style seating set up across a plaza. There was to be no food or drink. Fans were to wear masks, and show up with proof of a negative COVID-19 test within 48 hours of the show. All of this was okay, per public health rules, when it was organized.

We’re entering new territory. Even if the federal government coordinates a national effort to provide Canadians with vaccine certificates, even if provinces can get on the same page and even if ethical concerns are delicately mitigated at every turn, this will not be perfect. There will be problems we haven’t even thought of yet. But there may—there really, really may—be outdoor music.

Culbert, from the Canadian Public Health Association, would warn me not to get too excited. Even if some future iteration of the “Long Road Back” (the “Short Road Back”?) goes ahead with vaccine and testing requirements in place, we could be setting ourselves up for a false sense of security, he says.

The pandemic’s so-called third wave has gripped us in another excruciating race against time. Variants are spiking. Younger people are catching the virus more often, and reportedly getting sicker, while ICU beds are filling up in many parts of the country. At the same time, Canadians are tiring of endless, incremental lockdown measures. And the weather is getting warmer, making it easier to let our guards down.

But still I cling to the vision of an outdoor concert in the summer of 2021. It is my motivation to stay home. It is my source of optimism even on the darkest days, when it feels like we’re fighting a losing battle. I’m brushing up on one of Blink-182’s latest releases, an angsty 2020 anthem, whether I get to sing along live this July or not. “Quarantine, no, not for me,” the song goes. “I thought that things were f–ked up in 2019. F–k quarantine.”